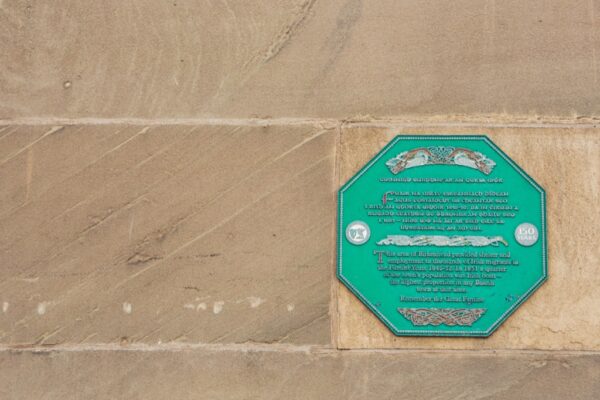

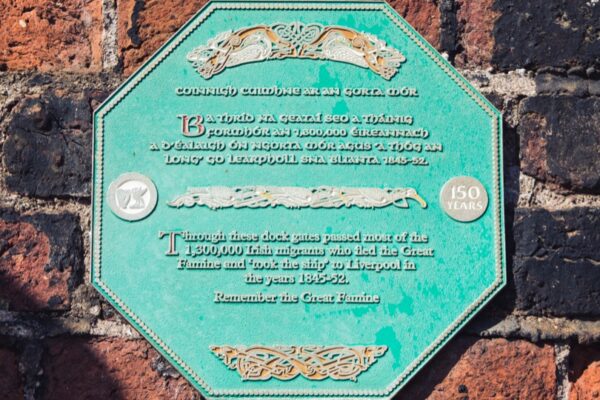

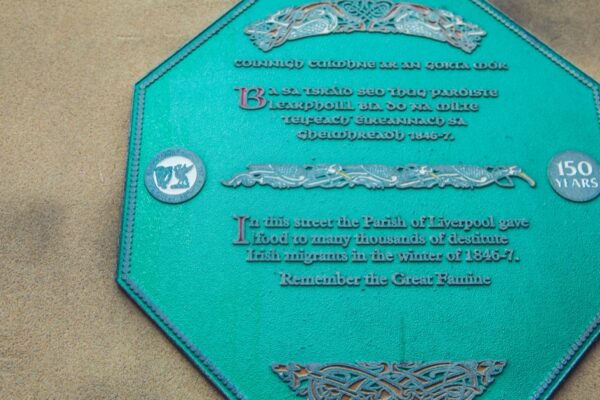

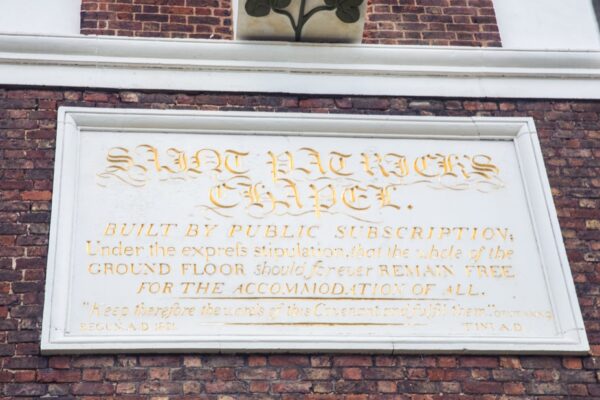

The plaque memorialises the existence of a significant Irish presence in the town of Birkenhead, as a place where Irish immigrants settled. Indeed, until the end of the century the area was a warren of courts and slums.

The plaque memorialises the existence of a significant Irish presence in the town of Birkenhead, as a place where Irish immigrants settled. Indeed, until the end of the century the area was a warren of courts and slums.

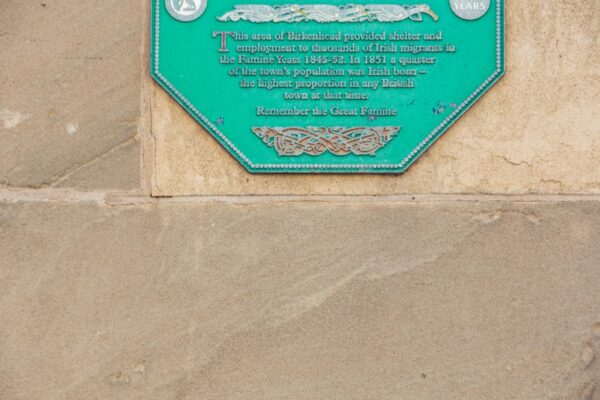

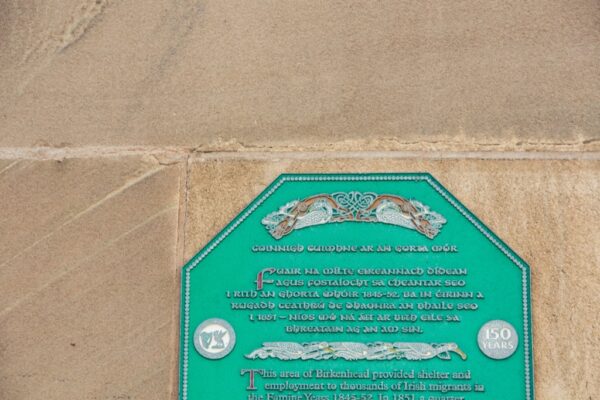

The plaque reads: “This area of Birkenhead provided shelter and employment to thousands of Irish migrants in the Famine Years 1845-51. In 1851 a quarter of the town’s population was Irish born; the highest proportion of any British town at the time”.

In 1841 Birkenhead’s population stood at 8,223; by 1851 it was 24,285 (Birkenhead History Society 2021), showing a considerable influx.

It is no surprise that with Liverpool brimming with new arrivals, Birkenhead became a destination for people forced from Ireland by starvation. In Price Street there was cheap accommodation available and -because of its proximity to a new dock system between Wallasey and Birkenhead -with the West and East Float (shared in 1844, hitting financial difficulty in 1847 and under Liverpool Corporation control by 1855)- there might be access to work.

Victims of The Irish Famine began to arrive in Birkenhead from about 1845 onwards. Select vestry minutes noted “the great influx of casual poor, particularly from Ireland” (Davey 2009). The vestry was required to call a parishioners’ meeting to raise additional funds and ask for further subscriptions from the parishioners. Money was duly raised and “many thousands of poor people were relieved” (Davey 2009).

Many of those who had arrived in Birkenhead had travelled via Liverpool and records show they were in a state of absolute poverty. A first-hand account by W Williams Mortimer (1847) records that:

Proceeding direct from the ferries to the parish office, their numbers -principally women and children- were so great, their applications for food so urgent and their destitution so apparent, that the ordinary law[s] of vagrancy were suspended. In the first quarter of the year, no less than upwards of two thousand… applied for assistance.

The familiar problems of overcrowding in lodging houses led to an outbreak of typhus, again hitting the Irish migrants hard. Unlike Liverpool, Birkenhead did not have a Medical Officer of Health. Management of the epidemic was undertaken by Dr Vaughan (more research required) who was the local Union Medical Officer. Dr Vaughan managed to persuade the guardians of the Wirral Poor Law Union (established 1836), to build a hospital to contain the outbreak of typhus in Livingstone Street (crosses Price Street, between Corporation and Park Roads). Reports of ‘pauperism’ in the area rose.

From 1852 to 1865 Birkenhead operated as a Government Emigration depot, organised with the laudable aim of providing clean accommodation for those in transit from Ireland to north America, Australia and other destinations.

It had some success, but the numbers using the service never reached the anticipated levels.

This is partly due to an outbreak of cholera in Birkenhead in 1849. Thought to have arrived from India in this instance, cholera is caused and exacerbated by poor sanitation, which allows the cholera bacteria to contaminate food and water.

The first death in this outbreak was “a poor Irish woman, aged 25, a lodger at one of the crowded lodging houses, no.64 Field Street- a decided case of Asiatic cholera” (Davey 2009).

Field Street is no longer a registered street, but it ran between buildings 96 and 98 Livingstone Street, to what is now Parkview Close, very close to Price Street.

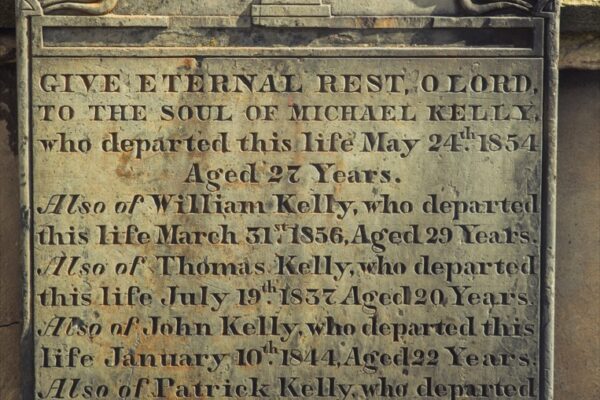

The graphic description of the Irish people arriving in to Birkenhead -as described by Mortimer- allows us to visualise their destitution, such that normal rules and bylaws about vagrancy had to be set aside to provide care and support. Although we do not know the identity of the Irish woman who was the first victim of cholera in Birkenhead, we know her circumstances well. She was poor, very probably in a weakened state of physical and mental health and living in crowded, unhygienic conditions. Thus, she was very susceptible to a pandemic outbreak of a contagious disease.

Crowley, Smith and Murphy, editors of the Atlas of the Great Irish Famine (2019) suggest there is an absolute requirement for “a diversity of approaches and perspectives in seeking to illuminate and represent the monstrous reality of the Famine tragedy and its consequences”.

The two examples cited, considering microlevel events in Birkenhead in the 1840s, illuminate and represent the monstrous reality of The Irish Famine and its consequences on individuals within the landscape of need. It reminds us of the importance in recognising that though Liverpool may have borne the brunt of the initial influx, Birkenhead -as a satellite town- also became a home or last-stop for many Irish people.

It is interesting that -in the close quarters surrounding Hamilton Square- lived the destitute and the aristocrat, pushed together by the sudden outpouring of people via Liverpool.

Mick Corry – General Michael Collins’s driver the night of his shooting at Béal na Bláth (Bealnamblath) in 1921- was born in John Street, just behind Hamilton Square to the north. Frederick Winston Furneaux Smith (1907-1975; better known to us as the Second Earl of (Lord) Birkenhead) -who developed an unlikely personal respect for Collins- was born in Pilgrim Street to the Square’s east; showing that upper- and working-class people lived cheek by jowl in the years following the mass-migrations.