The Wife of Michael Cleary is a musical theatre piece, devised and composed by Maz O'Connor. It is based on the 1895 murder of Bridget Cleary.

The Wife of Michael Cleary is a musical theatre piece, devised and composed by Maz O'Connor. It is based on the 1895 murder of Bridget Cleary.

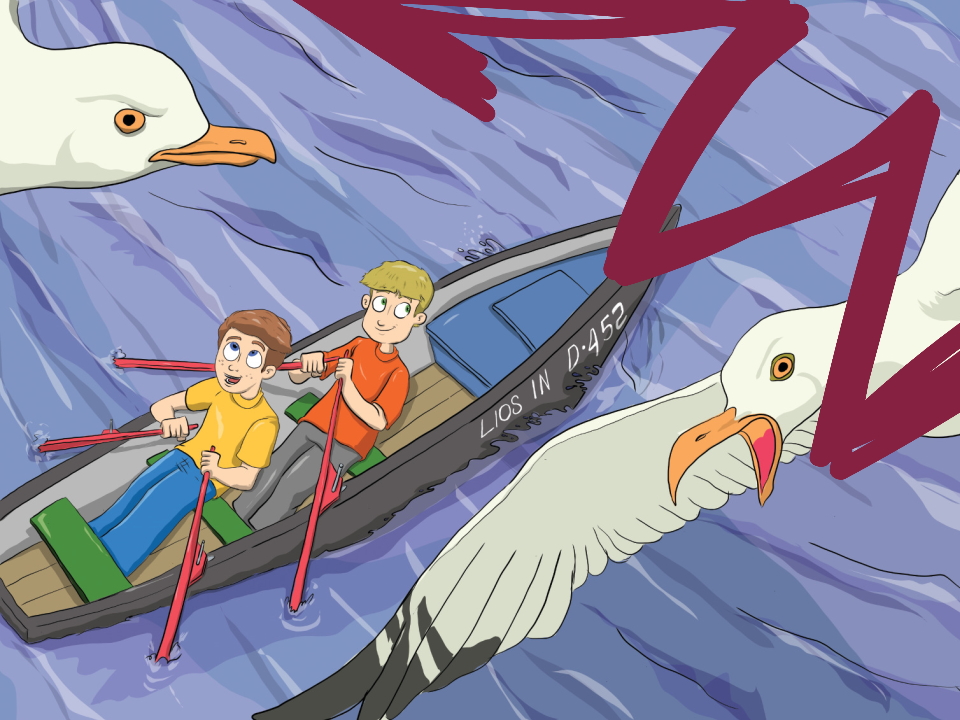

Glór ar Inis Gluaíre is a Nicola Lavelle's first children's book, based on Ireland's folklore stories of the Children of Lir.

Jack Byrne's contribution to 'Being Irish', a collection of 100 articles from the global Irish community Liffey Press (Dublin) in October 2021.

Each year, Culture Liverpool galvanises the city’s efforts to create, under a prevailing medium.

Get a short piece printed in this year's Festival newspaper, by entering our competition, held with Liverpool Year of Writing.

Maz O’Connor came to the Festival’s attention in 2018 when she discovered and shared stories unearthed about her family’s Irish connections.

A £1,000 commission is available for a creative project, centred on Irish and/or Gaelic creativity, to form part of #LIF2021.

In solitude I came at last on this exhausted ground,

Of tarmac, stone and railing

Where sandstone pillars bear quiet testament

To this abandoned field.

Sweet soil, that once gave birth to daffodils and snowdrops

To mark each year the hope of spring.

Now you lie trampled underfoot and barren

To hold on our behalf the burdens of the past,

As if it is that easy to forget.

Is there prospect of redemption here?

Should I stretch out upon this ground, as is the tradition,

To weep my tears into the soil?

Claw the senseless earth

Conjure it to life and claim it back?

Is there a city underneath this hardened skin?

Where souls more bone than flesh

Once came to rest here in the heart of Vauxhall,

America for them a dream too far?

No stones, no stunted grass or tarmac grit can now remember.

Nor children, nor passers-by.

Who now recalls that here a church once stood

To proclaim this derelict burial ground

Where old dead bones still tremble to the rhythm of the lorries’ thunder?

Here, your dignity in death was the kindness of strangers.

The grandeur of the church not granted,

The sky became your vaulted canopy

The salty mist your unction.

The merciful dark your coffin.

In threadbare winding sheet, by single candle-light,

They passed you down from hand to hand

Their solemn prayers each whispered to the wind.

Do lingering bones still cower here

Like the jagged ribs of some old shipwreck?

Are there skulls? Each an empty tabernacle

That once cradled memories of a life?

Here in this no-man’s -land

Light as a feather you were left.

And as they lowered you,

Might one last breath

Have been released,

To wing into the western sky

And escape this ground forever?

Written and provided by Greg Quiery, poet, historian and author.

Lockdown Lights is an open source project, collecting community stories about people’s experience of the lockdown during the 2020 Coronavirus restrictions. The project was funded by the Irish Government’s Emigrant Support Programme Covid-19 relief fund. We would like to thank all the participants and the Irish Government for their support.

Celebrated poet Eavan Boland passed away during 2020. To mark her passing and to the reflect the Coronavirus lockdown reegulations, we selected her poem, Quarantine, as one of two poems we asked people to record themselves reading and send back to us. The followin film was presented and debuted at the Festival’s digital #LIF2020 launch on 15 Oct 2020.

Eavan Boland, born Dublin, Ireland 1944-died Dublin, Ireland 2020.

In the worst hour of the worst season

of the worst year of a whole people

a man set out from the workhouse with his wife.

He was walking—they were both walking—north.

She was sick with famine fever and could not keep up.

He lifted her and put her on his back.

He walked like that west and west and north.

Until at nightfall under freezing stars they arrived.

In the morning they were both found dead.

Of cold. Of hunger. Of the toxins of a whole history.

But her feet were held against his breastbone.

The last heat of his flesh was his last gift to her.

Let no love poem ever come to this threshold.

There is no place here for the inexact

praise of the easy graces and sensuality of the body.

There is only time for this merciless inventory:

Their death together in the winter of 1847.

Also what they suffered. How they lived.

And what there is between a man and woman.

And in which darkness it can best be proved.

From New Collected Poems by Eavan Boland.

Copyright © 2008 by Eavan Boland.

Reprinted by permission of W.W. Norton.

All rights reserved.

Lockdown Lights is an open source project, collecting community stories about people’s experience of the lockdown during the 2020 Coronavirus restrictions. The project was funded by the Irish Government’s Emigrant Support Programme Covid-19 relief fund. We would like to thank all the participants and the Irish Government for their support.

As part of our Lockdown Lights project, we selected two poems and invited people to record themselves reading them, so we could geneate a film, to share as part of this year’s digtal launch.

Active, positive and full of creative hope, Stephen James Smith’s poem We Must Create was selected in counterpoint to Eavann Bolanf’s Quarantine. We thank Stephen for allowing us to use the poem and share his version below. Loo jout for our film from 15 Oct 2020.

We must create to know who we can be

I say this for you, I say this for me

We must create to know who we can be

Early beginnings, heart beat warmth and you

First breath, eyes open a new point of view

Hands touch, ears hear, clocks ticking I am who?

We must create to know who we can be

Screaming out from within with a voice here

Notes flowing on air lulling the fear

Melody all around this atmosphere

We must create to know who we can be

Hearing truth in onomatopoeia

Boom, boom, belch, zoom, zap, playing with grandpa

While cookie cutting, baking for grandma

We must create to know who we can be

From scrawling with crayons to Lego bricks

From knitting needles, soft textile fabrics

To air-guitaring auld Jimi Hendrix

We must create to know who we can be

There are creative accountants, CVs

Tinder profiles where you look the bees knees

But best not to force it, it comes with ease

We must create to know who we can be

We heard a song sung, it helped ease the pain

We didn’t feel so lonesome as we sang the refrain

We forgot that feeling until we heard it again

We must create to know who we can be

From nursery rhymes to white collar crimes

What have you to say in uncertain times?

Have you a chance to change the paradigms?

We must create to know who we can be

Do you remember the time you heard an opening allegro

Or when that beat dropped and how it made your head go?

Some things make no sense unless you’re in flow

We must create to know who we can be

You may rise then fall, or fall then rise

An arc of a story contains no surprise

But how you tell it, therein the art lies

We must create to know who we can be

Artistry gives rise to community

We’re all part of a changing tapestry

There’s art history in identity

We must create to know who we can be

If you do it for the money you’ll be called a fraud

If you think you’re great company and you might be God

Delusions of grandeur aren’t that odd

We must create to know who we can be

There’s all sorts of forms, disciplines, levels

To challenge yourself in the intervals

Where you’ll find rivals and reasons for approvals

We must create to know who we can be

If it’s saved you from yourself

And now there’s no other way

It doesn’t matter how it moved you, welcome to the ballet

You’ve just found the peak of Parnassus, fair play!

We must create to know who we can be

I say this for you, I say this for me

We must create to know who we can be

We must create to know who we can be.

From Here Now by Stephen James Smith.

Copyright © 2019 by Stephen James Smith.

Reprinted by permission of Pace Print and the poet.

All rights reserved.

Lockdown Lights is an open source project, collecting community stories about people’s experience of the lockdown during the 2020 Coronavirus restrictions. The project was funded by the Irish Government’s Emigrant Support Programme Covid-19 relief fund. We would like to thank all the participants and the Irish Government for their support.

Back in old glory days, long since forgotten,

The flags here were smothered in snowy white cotton.

Soft as a carpet beneath merchant feet

King Cotton was plenty, King Cotton was cheap

It came by the Mersey, it came by the seas

By white canvass aloft in the westering breeze.

By Liverpool sailors, nimble and yar

Tough as mahogany, weathered as tar.

It came from the rivers, it came from the mud

It came from the kick and the stick and the blood

It came from the work line, the whip, the plantations

It came from the fracture and breaking of nations.

For cotton is gentle, fragile and light

Cotton is pure and pristine and white.

But the commerce of cotton, darker than death

Would barter your soul and crush your last breath.

It went by the engine, the steam and the rail

It went by the hundredweight, bail over bail

It went by Manchester, Bury and Preston

Blackburn and Bolton, and Darwen and Nelson

Where there’s brass for the boss, and poor spinning Jenny

Works hour by long hour for less than one penny.

Where the air is so thick it smothers the lung

And thundering loom drowns the Lancashire tongue.

Cotton by boll, by bag and by bale

For smocks and for shirts, for duck cloth and sail.

Cotton for mills, for ships and plantations

Enriching mill owners, impoverishing nations

Cotton for tyranny, hardship and slavery

Cotton for unions, resistance and bravery

Back in its glory days, long since forgotten

It came by the Mersey, that snowy white cotton.

Written and provided by Greg Quiery (20 Aug 2018), poet, historian and author.

Lockdown Lights is an open source project, collecting community stories about people’s experience of the lockdown during the 2020 Coronavirus restrictions. The project was funded by the Irish Government’s Emigrant Support Programme Covid-19 relief fund. We would like to thank all the participants and the Irish Government for their support.

This poem was offered specifically in relation to the Black Lives Matter protests of summer 2020 following the brutal murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA on 25 May 2020. Black Lives Matter. Full stop.

In:Visible Women have long been a focus of the Festival. We’ve seen many unveiled over the years; often the equally strong partner of a famous man (such as Constance Markievicz or Maude Gonne). Alternatively, they have had their light diminished because they did not fit the social-stereotype (Eva Gore-Boothe) or threatened the patriarchal order (Kitty Wilkinson) or their time. Gradually they are coming in to the light. Here, Helix Productions offer some additional background to their play Mrs Shaw Herself, a production we are moving in to the digital arena for #LIF2020 and hope you will attend.

“I found that my own objection to marriage had ceased with my objection to my own death”

George Bernard Shaw on his marriage to Charlotte Payne-Townshend in 1898

Let’s face it, this does not sound the most romantic start to a marriage; especially if you throw in that the groom and bride were both over 40 with a disdain for -if not downright aversion to- sexual activity. Add further that the groom was one of the most famous men in the world, at that time, and an avowed philanderer (albeit more on the page than in the sheets) and we can but wonder at how this marriage lasted over 40 years, ending with Charlotte’s death. Shaw once said “I could never have married anyone else”. So how is it that we know so little about her?

Creators and performers of Mrs Shaw Herself –Alexis Leighton and Helen Tierney- have found that after performances of the show, audience members frequently come up to tell them they were in fact unaware Shaw was married. Yet Charlotte’s is a fascinating story. It was a mammoth achievement to stay married to the Nobel Prize and Oscar-winning Shaw, in itself, but Charlotte needs to be remembered and indeed celebrated for so much more.

Like Shaw, she played an active part in the early Fabian movement, but it was her money -and it is her name- which gave the London School of Economics their beautiful Shaw Library. She gave financial assistance to many women who were studying medicine and supported the suffrage movement. She not only assisted Shaw with secretarial work, but in his research for plays; notably St Joan. Shaw thanked her with a commission of a St Joan statue to grace their garden at Ayot Saint Lawrence. She read voraciously and enjoyed an intimate and frank relationship with T.E. Lawrence, taking on a quasi-maternal confidence with him in letters.

Shaw and Payne-Townshend’s story is the most maverick of Irish love stories. Charlotte was born in Cork to an incredibly rich family; by coincidence George had worked briefly as a clerk in a land-registry office, owned by her family firm. She had given up on marriage, after failed love affairs, when she met Shaw and our show tells of the twists and turns of their courtship, noted by eagle-eyed Fabian Beatrice Webb. The marriage had its challenges. Shaw could not resist a pretty face and whilst it hardly ever led to physical contact, Charlotte sometimes felt the need to take him on long holidays abroad just to get him away, especially from actresses. Shaw’s infamous affair with Mrs Patrick Campbell was a particular low point, but the marriage weathered it and if nothing else, Mrs Shaw Herself is a lilting (and sometimes keening) Irish song of praise to the long-haul of marital love.

The Liverpool Irish Festival’s theme of “exchange” is embedded in the story of Mrs Shaw Herself. Both Payne-Townshend and Shaw exchanged Ireland for England, but never lost a sense of their roots. They were prominent in support of a united Ireland and of Roger Casement. As Irish Protestants in a sea of Englishness their outsider status brought with it an independent, if not downright maverick stance to life and matters; it is this element that many love in Shaw’s plays. Charlotte exchanged -as did George- a life-long suspicion of marriage for a compromise in what seems to be a celibate, but ultimately loving and supportive relationship. He did not exchange, however, her feminist stance and her determination to use her fortune -in part- to better the lives of women and, most importantly, to create systems for that. The care she took in supervising her scholarships at the LSE and the London School of Medicine is quite astounding. Whilst researching the play, Leighton and Tierney were given access to the wonderful collection at the LSE of photos taken by Shaw. You get a real sense of partnership and affection through the pictures; this between two very independent people.

Mrs Shaw Herself has been performed in many locations; cathedrals, theatres, libraries, centres and even at the wedding of Charlotte’s great-great niece Elisabeth Townshend. It was good to hear Charlotte’s words ring out in the Shaw Library for a conference on women at our LSE performance and at the church in Shaw’s home village of Ayot at which the organ, which Shaw occasionally played, sounded at Charlotte’s funeral scene as described in Shaw’s letters. We have taken the show to various festivals including Bloomsbury, Edinburgh, Crouch End, Watford and Bury St Edmunds, but it is wonderful now to bring an online version of the show to the Liverpool Irish Festival. Do come and hear the voice of the woman who was not only Mrs Shaw Herself, but so much more.

Mrs Shaw Herself is performed at the Liverpool Irish Festival at 8pm, Wed 21 Oct, online. Click here to book tickets, whilst available.