Nigel Baxter is a Liverpool Irish stone mason.

Liverpool has a ubiquity of stone – from the smooth Asian slate of Liverpool ONE, to the warm red local sandstone of the Anglican cathedral; the corbels of St Nicholas’s Church and the Irish granite of the dock kerbstones and Irish Famine memorial. Interesting for us then that Nigel’s most recent work has revolved around two creative men, of Irish lineage, where an exchange of respect has generated legacies for each. Nigel tells us why.

There were three main factors that set me on a course of discovery about Seamus Murphy and Robert Tressell.

Part 1: Seamus Murphy arrived in my life by chance, whilst -as an enthusiastic and eager stone carver’s apprentice- I stumbled across his semi-autobiography Stone Mad in my local London library. Dwarfed between large art reference volumes, its insignificant size was compensated by its title. It was a book that transpired to inspire one’s life and it became my personal bible. We had a lot in common. Although from different generations, our training and experience were mirrored in such ways that I came to conclude, much later, we shared an affinity only craftsmen identify with; a sort of mutual bonding. Even though we never met (he died two decades before) I felt connected through his writing and -indeed later- this was substantiated when meeting his children during the project.

Whilst talented and recognised as one of Ireland’s great sculptors, Seamus was a quiet reserved character and (indicative of many creative people) very modest about his skills. This was demonstrated by a visit to his native city, Cork, where despite many examples of his work I found nothing to identify the man himself. It was as if he had dissolved into obscurity, leaving a trail of ghost-like artwork. So, who better than I to carve -in stone- his portrait, thus immortalising an important craftsman who had influenced my creative development? I was determined to dig deeper.

My first port of call was his art college. Among my findings was a list of short films and documentaries, relating to Seamus and his craft. This finding developed in to a friendship with a film director, who had aired a life documentary on Irish television. Our meeting was overwhelmingly successful and a deal was struck to film my project. Additionally, I was offered a residency at the art college, with full workshop facilities. This was the opportunity I had hoped for and, armed with this encouragement, I sought approval from Seamus’s immediate family, seeking examples of images of him. On producing a limited number of photographs it was collectively agreed to opt for a posed publicity shot and an editorial photograph, each taken in mid-life, which we felt showed his finest qualities, both for age and imagery.

The carving of stone is an intense experience, not to be hurried. Indeed each craftsman has their own pace and relationship with the material. For me, I find that speed is not a requisite to final accomplishment; my technique is relatively quick and therefore the carving of a full size bust, depending on the stone, averages between 120 and 150 hours. In Seamus’s case the procedure took longer, to allow for lighting and camera angle adjustments, working from just two images.

We had a number of inquisitive visitors, due to press and college publicity. Among them was one of Seamus’s daughters. Whilst not unaccustomed to being in a carving workshop, she viewed the developing image of her father with a mixture of trepidation and relief; although it had been some years since his death (she was in her eighties), and with recognition fading, there was delight to finally witness an immortal reminder of her father’s greatness, for me the ultimate accolade.

Part 2: Hastings (East Sussex) is the quintessential English south coast town. It has predominately retained its quirky late-nineteenth century seaside characteristics, still attracting a colourful hotchpotch of inhabitants, mirroring the social backdrop described in (possibly) one of the most poignant political/social stories to ever be written. Its title was not unfamiliar to me, having an odd ring of eccentricity about it, so it was only natural for me to pick up a copy of The Ragged Trousered Philanthropist whilst browsing in an alternative book shop nearby.

Robert Tressell was an Irishman, born in Edwardian Dublin. He lived such a life of diversity that only someone with his experience, coupled with that talent, could reiterate -so succinctly- the life of the working classes of the time. There were so many positive testimonials, by some very learned people, arising from this book that I needed to pursue the man behind the pen. My investigations took me on a journey to Dublin, uncovering the complexities that fashioned his fascinating mind; from child to man.

When creating a bust the challenge is not just about the physical execution, but interpreting characteristics…this can only be done when you are aware of as much of that person’s history as is possible. Indeed, it’s not unusual for the features to appear from the stone block, to catch me in conversation with them, expounding theories and unanswered questions for which I know there to be no answer. This only encourages my drive to illicit and expose as much about the person as possible from the inanimate stone.

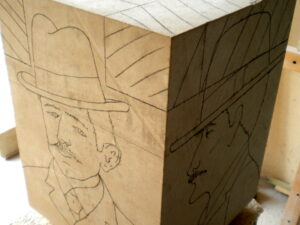

Discovering quality images of Tressell was even harder than of Murphy. In the literature about him, only one grainy black and white full frontal image appears, used repeatedly. Additionally, one crowd photograph –an aerial shot from behind- depicts Tressell among 200+ people wearing his very distinctive Homburg hat, which he wore unfailingly. My use for this was to capture his hairstyle, which he wore thickly as opposed to the favoured short back and sides of the times.

Sadly, there was little interest from local authorities or dedicated Tressell followers, despite radio and press coverage. This I’ve come to accept when an artist undertakes a project that hasn’t been officially recognised or commissioned. In both my Murphy and Tressell projects there has been little recognition from those claiming an overall interest in their causes. To this I’m quite resigned; these projects are my personal statements that demonstrate there are people past who deserve recognition and immortal recognition.

Part 3: This brings me to my third layer of inspiration: the links between these two men. Initially it wasn’t obvious to me, but soon I became aware of the similarities. Along with their Irish heritage, Murphy and Tressell’s lives run in parallel. For the most part their lives correspond to creative skill development and use; each sharing a literary talent born out in their books, written with dedicated passion on their respective subjects.

Whilst Seamus died in his home town of Cork, Robert sadly died here in Liverpool, attempting to earn his and his daughter’s passage to Canada. There’s similarly little significant remembrance of either.

I now reside both in Cork and Liverpool. As for our notable characters of creation? They still hide behind a cloak of obscurity in storage in their respective cities, waiting for public recognition that they both so rightly deserve.

Nigel has a project page for his Seamus Murphy work, which you can access here.