Across the Festival, we have asked our partners, collaborators and artists to consider “exchange”. It is a means of connecting the programme to provide a cohesive message, whilst also demonstrating the benefits of coming together, even during times when this cannot be physically so. In the following article, Dr Ó Donghaile illustrates why Oscar Wilde was so ahead of his time, when it came to views on exchange and the benefit of art and culture to society. As Deaglán’s work on Wilde expands, we aim to continue sharing his research, looking more deeply in to Wilde’s enduring legacy, the lessons he left us with and how such a man might be received today.

Oscar Wilde: Art, Culture, Democracy, and Exchange

Dr Deaglán Ó Donghaile; British Academy Research Fellow, Liverpool John Moores University

Throughout his life, Oscar Wilde believed passionately in the importance of cultural and artistic exchange. He argued that art and literature were part of the common human heritage and that they should be shared among everyone. At a very early stage in his career, and long before his most famous literary works were published, Wilde set out his ideas on literature’s centrality to culture when he gave his first lecture in the United States. In this talk, entitled Our English Renaissance (first delivered in New York City, January 1882, and then at different venues across the US), Wilde told audiences that Aestheticism –the literary and artistic movement of which he was a leading figure- was not an exclusive club. It was a movement dedicated to the sharing of artistic, cultural and literary ideas. He believed that the enjoyment of beauty should be experienced and enjoyed by all and widely exchanged.

In his lecture, Wilde pointed out that similar ideas and theories had already been proposed by poets, philosophers and painters from antiquity to the nineteenth century. His long list of international figures included Homer, Plato, Aristotle, Sophocles, Geoffrey Chaucer, Dante Alighieri, Michelangelo, Albrecht Dürer, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Giuseppe Mazzini, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Lord Byron, William Blake, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Walter Scott, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, William Wordsworth and John Keats. He also included more recent writers, artists and critics, such as John Ruskin, Algernon Swinburne, the Pre-Raphaelite painters, Charles Baudelaire, Edgar Allan Poe, Walt Whitman and William Morris.

Wilde described Aestheticism’s renewal of culture as ‘our English Renaissance’. As an Irish writer he was clearly stating that art and culture could be shared outside limiting national boundaries. This, he insisted, could democratise art because it represented ‘a new birth of the spirit of man’ resembling the Italian Renaissance in its promise of ‘a more gracious and comely way of life’. With its modernisation of ideas of beauty and form, it promised ‘new subjects for poetry, new forms of art, new intellectual and imaginative enjoyments’.

Wilde believed that Aestheticism provided ‘a nobler form of life’ and ‘a freer method and opportunity of expression’. Cultural exchange was critical to this, as it imbued art with its essential ‘vitality’ in ‘this crowded modern world’. For Wilde, the world was a global community in which everyone should participate in art and culture. This made his views on culture explicitly political, as he felt that the best art was both historically engaged and socially conscious. Through the exchange of artistic and cultural ideas, every rank in society could experience the best that was offered by a broad, constructive and collective culture, without sacrificing the individuality of anyone.

This idea of the importance of mutual exchange within art and culture was a radical, democratic and republican notion. Wilde explained that Aestheticism, with its ‘passionate cult of pure beauty, its flawless devotion to form, its exclusive and sensitive nature,’ drew its inspiration from the French Revolution because democracy was ‘the most primary factor of its production’ and ‘the first condition of its birth’. Because it was democratic and transnational, art could transmit ideas about the possibility of a better life through ‘noble messages of love blown across the seas’.

Social and cultural exchange was the ‘definite conception’ of art because democracy was its ‘root and flower’. The artist could present ‘a vision at once more fervent and more vivid, an individuality more intimate and more intense’, fully charged with culture’s ‘social idea’ and its ‘social factor’. Wilde argued that culture’s potential lay in this shared reality. In it was found ‘that breadth of human sympathy which is the condition of all noble work,’ allowing it to express shared ideas, ‘as opposed to… merely personal’ ones. Art’s capacity to change people and society lay in its potential to convey ‘the love and loyalty of the men and women of the world’.

Wilde believed art should connect and transform people; he regarded it as a social practice that countered the alienating and privatised logic of competition and separation being imposed by modern capitalism. Exchange was culture’s ‘method of its expression’ because art conveyed the reality of the world. This had political implications for Aestheticism. As an internationalist and an Irish republican, Wilde was very conscious of the need to share and exchange cultural and artistic ideas across borders: ‘All noble work is not national merely, but universal’ he declared; ‘the political independence of a nation must not be confused with any intellectual isolation’.

For Wilde, art, literature and culture were forces for human unity and expressions of ‘perfect freedom’. He felt that ‘devotion to beauty and to the creation of beautiful things’ was ‘the test of all great civilised nations’. Through its constant exchange of artistic and social ideas, and sharing of literary and political thought, Aestheticism could contribute to the cause of international peace because ‘national hatreds are always strongest where culture is lowest’. His lecture also emphasised that art and culture could unite artists with the working class: ‘between the singers of our day and the workers to whom they would sing there seems to be an ever-widening and dividing chasm, a chasm which slander and mockery cannot traverse, but which is spanned by the luminous wings of love’. Wilde would return to these ideas about global peace and the urgent need to remedy class conflict nine years later in his famous essay The Soul of Man Under Socialism’.

Today, at a time when questions of cultural inclusion and national belonging are being raised in Ireland, and elsewhere, we can still learn much from Oscar Wilde’s thoughts on the importance of sharing and exchange. Describing this practice as ‘the correlation of art’, he spent the rest of his life writing about the connections that drew people together in the hope that unity and understanding would ‘sweep away’ the barriers of class and empire that separated people from one another.

Dr Deaglán Ó Donghaile is a British Academy Research Fellow at the Department of English, Liverpool John Moores University. His latest book, Oscar Wilde and the Radical Politics of the Fin de Siècle, will be published by Edinburgh University Press in November. He is currently writing a critical biography of Oscar Wilde entitled Revolutionary Wilde.

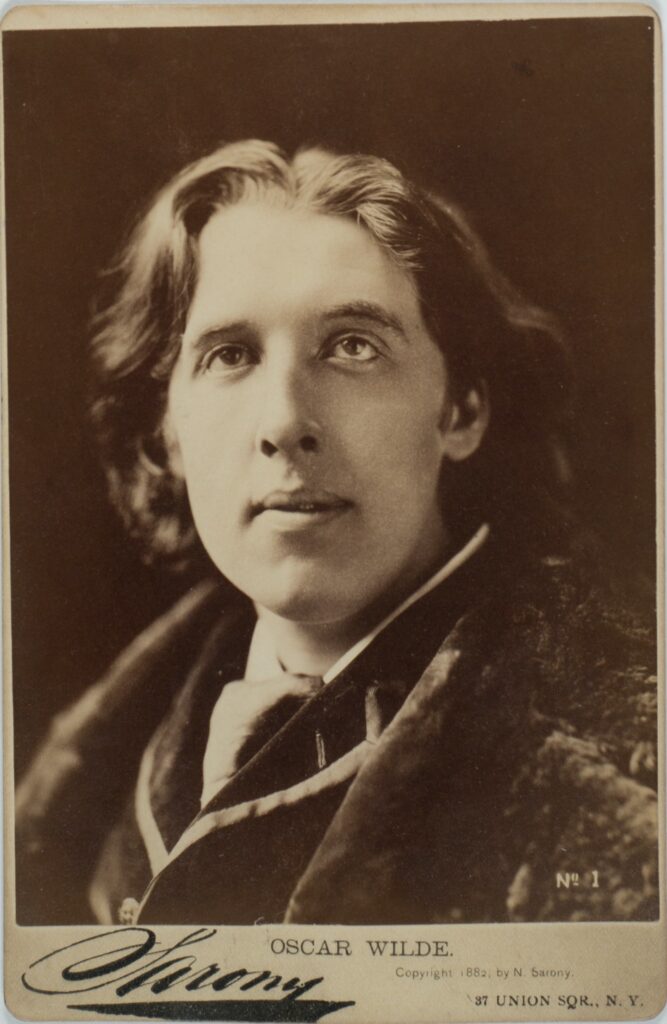

Image Credit: Publicity photograph of Oscar Wilde, taken in New York by Napoleon Sarony in 1882, used under creative commons licencing from the website Oscar Wilde in America: A Selected Resource of Oscar Wilde’s Visits to America. https://www.oscarwildeinamerica.org/sarony/sarony-photographs-of-oscar-wilde-1882.html, accessed 8/9/2020.