Sub-title: A quick, short, and linear exercise to map the Royal Charter’s failed-return to Liverpool against the history of weather forecasting.

<<<During lockdown, Derry-based Hong Konger, artist Edy Fung has used weather to help motivate her working cycles.

In doing so, she has studied meteorological history, finding links between Derry and Liverpool. Edy’s generated an essay on this, complete with archive images. This sustains a digital relationship with the Festival that began for #LIF2020, advancing our work with Art Arcadia, where Edy is a resident artist.

The connectedness of internationalism, nature and platforming female voices sits within the St Brigid’s Day ethos of progressive acts and equality. We thank Edy for her work and ability to express her layered thinking to bring us something thought-provoking, fascinating and unexpected. You can learn more about Edy at the end of this article.>>>

2020 has overwhelmed the world with how fast every aspect of our daily lives can change for a new normal.

After the pandemic, we have all learned to be humbled by external impacts and environments. Most of us in different parts of the world meandered our way through lockdowns; rethinking our new normal. We have had to learn to adapt to uncertainties, getting used to making our plans with spontaneity, but ready to have them canceled or postponed. It is difficult. We always want an answer for the future; while we look for ways to predict it -analytics, predictions, prophecies- these very methods demonstrate that the need for human beings to ‘imagine’ is inevitable.

My name is Edy; I am an artist who lives and works in Derry, Northern Ireland. I have begun research on exploring atmospheric patterns and their implication on societal and political shifts in macroscale*, bringing these discoveries into a personal, bodily and relatable scale. My artistic practice currently aims to connect human sentiments, affect, weather, politics, science, and technology after the Anthropocene^. This piece of writing, commissioned by the Liverpool Irish Festival, will form the foundation of another online collaborative project: The Meteorological Cartomancer that looks at the beauty of chance and collective feelings. Perhaps, borrowing from the temperament of the Greek Tragedy aesthetic form, I am making some reflections for this day and age; arising from the story of the storm that hit the Liverpool-bound Royal Charter (ship) in 1859 on its journey through the Irish Sea, to incidents concerning geographies of both sides of the water.

* involving general or overall structures/processes, rather than details.

^ the geological time during which human life has impacted the earth.

This is an attempt to trace our desire to foresee the future during uncertain times. It documents the first time in history that humanity came close to future ‘prediction’ with a scientific foundation. I am drawn to look into the 1859 storm that shipwrecked Royal Charter in the Irish Sea. Prior to this, the weather was believed to be an act of God and if a storm came, so be it. This storm -and the resulting shipwreck- holds a vital place in pushing advancement for what is known today as ‘weather forecasting’.

The Royal Charter was a steamship built in Sandycroft Ironworks, on the River Dee, as one of the fastest ships at the time. On the evening of 25th October 1859, the steamship was bound to make the last leg of its 60-day cross-continental journey from Australia. When it left Queenstown -in the south of Ireland- to return home to Liverpool, it encountered a gale so fierce that it rose to a hurricane force 12 on the Beaufort Scale (devised by Irish hydrographer Francis Beaufort in 1805), pushing the ship towards Anglesey (Wales), causing it to sink.

Here, I am excavating materials from the MET archive, starting with one of several (consistent) testimonies documented from people from Wales and Ireland, who recalled the weather and witnessed something more unusual before the storm:

“On Tuesday, 25th, I could perceive nothing at all unusual in the appearance of the weather, till, at half-past seven, when in the neighbourhood of Ballinamar and Ballyporeen, about, I should say, 12 or 14 English miles west of Athlone, the sky being free from clouds, I saw, in the direction of the Pleiades, a meteor. At first, when I saw it, it was about the size of a star of the first magnitude; it advanced swiftly towards me for about four or five seconds, rapidly increasing in size, and appeared to be coming so straight towards where I was that it created alarm; the colour was an intense white light, similar to the electric spark. At the end of the first four or five seconds it changed colour to a bright ruby red, and it seemed (but of this I could not speak positively) then both to change its course and to lose its velocity; while the red colour remained was not more than one-and-a-half to two seconds. It then burst into about, I should suppose, 15 or 16 bright emerald green particles, which, after remaining visible for about two more seconds, disappeared altogether. I saw nothing more that night. I arrived at Athlone about 12 o’clock, and up to that period the sky was quite clear and calm, and there was not the slightest appearance of storm. I was much astonished to hear, on my arrival in Dublin, on the night of Wednesday, 26th, of the violent storm that had taken place on the coast of Wales. […] I could not but think that the fall of the meteor had some connexion with the storm”.

— Thomas. T. Carter (Annual Report 1862, page xl).

This Royal Charter shipwreck, which occurred in the Irish Sea during the closing leg of an incredible adventure back to Liverpool, is linked to the emergence of weather forecasting. The MET Office was not established properly at the time, in the way we understand its function today; it was a position that Robert Fitzroy was taking as the ‘Meteorological Statist’ (Fitzroy’s term), advisor to the Board of Trade for the marine industry and the military. Responding to the Royal Charter’s demise, Fitzroy worked intensively to understand how how the shipwreck could have been prevented. He wanted to avoid further tragedies in the future. Next, we will see in more detail his research on new methods of using barometers, and his invention of meteorological telegraphy and weather map that led to the existence of the weather forecasting system.

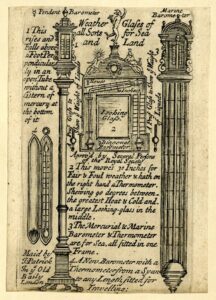

Under pressure: Barometers

In the 19th century, barometers were used inside boats and ships to detect the change of the atmospheric state, mostly for localised usage. These were the instruments most closely associated with a scientific method, reliable enough to provide “some definite idea of the amount of change which indicates unusually violent wind”. Such barometers could react and fall at the rate of nearly a tenth of an inch an hour before the shift of wind occurred. Fishermen and sailors would take this drop of pressure as an indicator of a storm, so they could decide whether to proceed the voyage or to find shelter.

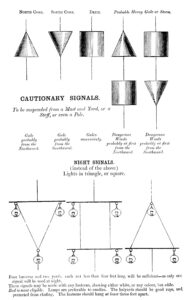

Cautionary Signals, Storm Telegraphy, Lighthouses

In February 1861, Cautionary Signals were initiated.

According to the report of Meteorological Department of the Board of Trade, Fitzroy tried to argue his case about the idea of giving storm warnings using telegraphy before 1836, in American and Europe, “Yet the subject attracted too little popular interest to be taken up by any influential body until September 1859.” (Annual Report 1862, page xi). We do not know the reason why these telegraphic storm warnings were not adopted earlier. The system of measuring wind conditions was already created by Francis Beaufort (an admiral from County Meath, Ireland), but only appeared in his diary in 1806, kept private in navy logs instead of broader application. He created the ‘Beaufort Scale’ to estimate the force of the wind, in a range from 0 to 13. The Royal Charter Storm was classified -under Beaufort Scale- at number 12. In 1859, the same year as the shipwreck, the British Association for the Advancement of Science finally proposed to the government a trial plan by which the approach of storms might be telegraphed to distant localities. By 1862 20 stations were built to establish the telegraphic communication of meteorological facts.

By 1863, more barometers and stations were dispersed on the coasts of Great Britain and Ireland. Locations sending cautionary storm signals -through both electric and magnetic telegraphs- reached 97, including 24 in Ireland (some of which today remain as lighthouses). Blacksod Lighthouse (County Mayo) was constructed in 1864, becoming the first land-based observation station in Europe, where weather readings could be professionally taken on the prevailing European Atlantic westerly weather systems. It became famous for reporting the fierce weather that delayed the Normandy Landings and saved D-Day. What would Fitzroy say about his legacy if he could see that his application of storm telegraphy had affected the ability of trained personnel to change the course of a world war? It was more than merely saving us from a natural disaster, but also humanitarian and political catastrophe when these telegraphic signals came to function.

As good as the technological advancement was, a data cloud did not exist at the time. However, their name today suggests a historic connection to these meteorological transfers and the early days of communications, continuing to demonstrate the importance of the Royal Charter’s legacy.

The first network of meteorological communications has laid the foundation for development towards the concept of a global system of interconnected computer networks; the internet and global information storage. The archive revealed Fitzroy’s continuous contact with observatories including Paris, Berlin, Rostock, Hanover, Turin, Copenhagen, and Gothenburg. Some of his correspondence with Urbain Le Verrier can be read in the 1864 report. Le Verrier is recognised as the pioneer who proposed the concept of a chronological map for storms and weather changes. These are some of the first data visualisations and analytics, now traceable in our data clouds (I am doing this exercise).

Weather Maps

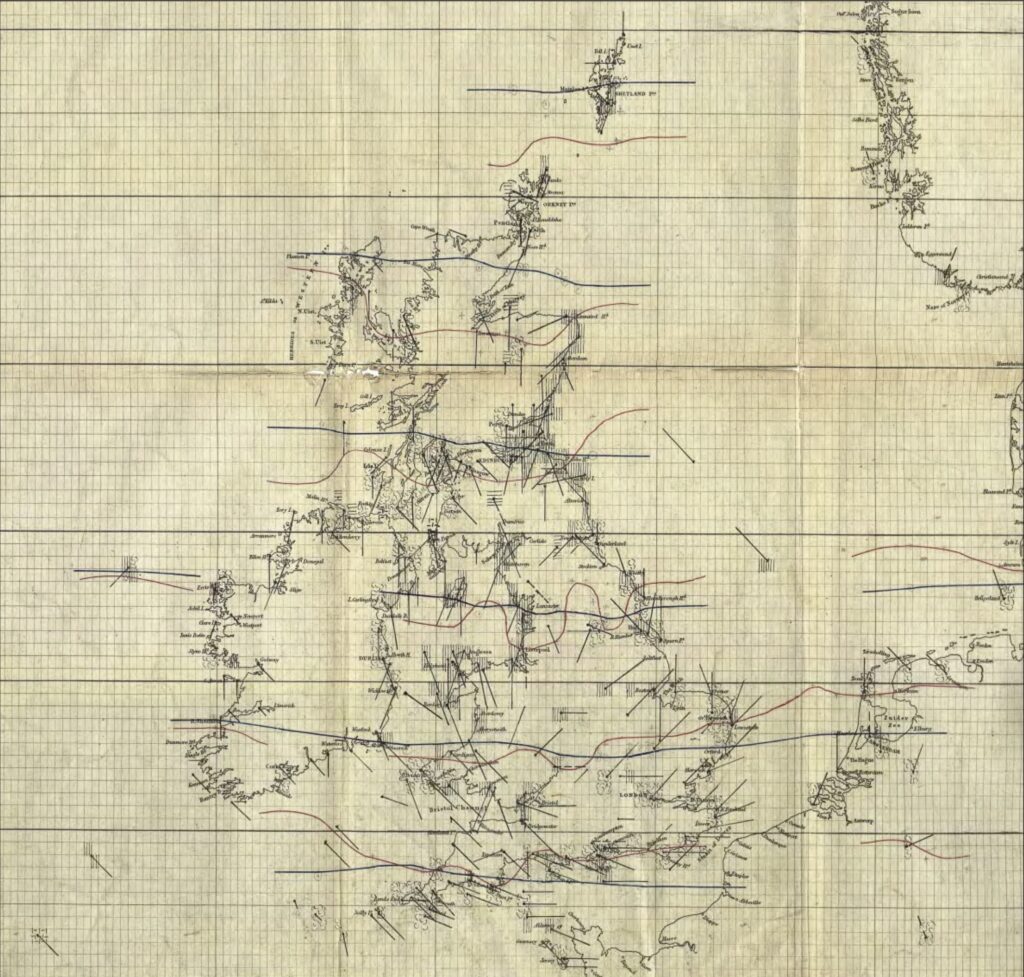

The following are some maps that Fitzroy made to analyse -retrospectively- the Royal Charter’s devastating storm, looking at changes between 25th and 26th October 1859. The arrows were drawn to indicate the wind direction as well as the strength of the wind (in proportion to the length of the line).

These maps were called ‘synoptic charts’, according to Fitzroy, providing a visual synopsis of the weather observations at a or any given time. The below chart by Fitzroy is claimed to be the oldest in the MET collection, suggesting that he could be the first inventor, after Urbain Le Verrier’s vision, of what we understand today as the weather maps. However, it is Francis Galton who is recognised as the first devisor of the weather maps instead (in the method same as today), and he wrote the 1863 book Meteorographica, or Methods of Mapping The Weather in the similar times as Fitzroy’s research. Galton was appointed to substitute Fitzroy’s position and the pivotal figure in the development of weather forecasting in the later years by focusing on remedying the speed and capacity of data collection.

To see these charts as gifs, showing the air movement, click here.

Weather Forecasting

“In August 1861 the first published “forecasts” of weather were tried; and after another half year had elapsed for gaining experience by varied tentative arrangements, the present system was established. Twenty reports are now received each morning (except Sundays), and ten each afternoon, besides five from the Continent. Double forecasts (two days in advance) are published, with the full tables (on which they chiefly depend), and are sent to six daily papers, to one weekly,—to Lloyds,—to the Admiralty, —and to the Horse Guards, besides the Board of Trade“ (Annual Report 1862, page v).

The term “weather forecast” was coined by Fitzroy. Taken for granted today, few of us can imagine that weather forecasting was an impossible concept and so ahead-of-its-time that it encountered plenty of skepticism and restraint. When the first public weather forecast was published in August 1861; its reception was not smooth and was been challenged for a period. Fitzroy had to state, repetitively, that the ‘weather forecast’ differed from general scientific methodology and should be considered as precautionary advisement – “prophecies or predictions they are not:—the term forecast is strictly applicable to such an opinion as is the result of a scientific combination and calculation”. To quote Fitzroy’s own words from 1863:

Many may ask—” Is this system of weather telegraphy sound and advantageous ” ?—If so, why is it opposed? There are no less than four distinct classes of interested opponents, and they should be known. First:—Certain persons who were opposed to the system theoretically at its origin, and having openly expressed, if not published, their objections, are naturally reluctant to adopt other ideas until converted. Secondly.—A numerous body who cannot have had time and opportunity to look tally into the rationale, but do not realise any want of special information, undervalue the subject, assert it to be a “burlesque,” and misquote really great authorities. Thirdly.—A small but active party which failed in establishing a daily weather newspaper indirectly opposed to the Board of Trade reports, and have since endeavoured, by conversation, by letters, and by elaborate criticisms in newspapers or periodicals, to exaggerate deficiencies, while ignoring merit in the works of this office, however beneficial their intended objects. And fourthly, those pecuniarily interested individuals or bodies, who would leave the Coasters and the fishermen to pursue their precarious occupation heedlessly—without regard to risk—lest occasionally a day’s demurrage should be caused unnecessarily, or a catch of fish missed for the London market. 14. Especially referring now to persons who would have the warning signals, but not the ” forecasts” (results of considerations on which the signals depend), may I quote from my “Weather Book” the following words?—”Frequently, remarks in favour of the cautionary signals, but in depreciation of the forecasts, have been made. Their author now begs to say that it is only by closely forecasting the coming weather, and by keeping atmospheric condition continuously present to mind, that judicious storm warnings can be given. Forecasts grow out of statical facts, and signals are their fruit” Weather Book, p. 193. Second edition. (1863 page v)

Less than a year after publishing The Weather Book: a manual of practical meteorology, Fitzroy died by suicide. Despite having proposed the idea of having the central office, to gather weather information (the MET office’s function today), he did not live long enough to see it. The literature he left us reveals his frustration and the great deal of difficulty he faced, while painstakingly realising an accurate weather forecasting system. Similar to the rise of today’s ‘cancel culture’ many rejected its merits, missing the goodwill and opportunities weather forecasting provided to change things for the better. It took a long time to gain traction, until public forecasts were produced in 1879, and became reliable in the 20th century after 30 more years of data accumulation.

Weather forecasting in today’s definition is “the application of current technology and science to predict the state of the atmosphere for a future time and a given location” (Science Daily). The use of both deterministic and probabilistic models is, nowadays, common and continually improved in applications beyond the weather, such as population, economy, energy forecasting and even in the betting industry. Provided the accuracy and the period (normally up to 14 days) that contemporary weather forecast can achieve, we are accustomed to treating the weather reports as valid predictions and make our plans around them. Perhaps this has also fueled our beliefs in the capacity of knowing the future in advance, as long as we have enough scientific tools. Then -logically speaking- one has to believe that the future is fixed and unchangeable, all to be determined by whatever data we have today, if we carry on with our obsession to predict something.

While it might be useful to know the future, we should imagine possibilities -and take positive actions- regardless of whether the future is predicted or not. Like the weather, a lot of things -viruses, traffic, public opinions- operate in a chaotic system; a butterfly flapping its wings can cause a hurricane on the other side of the world. History tells us that working with others, through long-term back-and-forth dialogues (sometimes cross-nationally towards a common goal), was crucial to confront macroscale events and reach solutions together for the betterment of society.

In this difficult time of the Coronavirus pandemic, would it not be more effective if we work together globally, using the best of our technologies, to find future-proofing solutions despite the naysayers, detractors, and decriers? Let us not stop listening to each other, no matter how far we are apart as we are all interconnected, prone to the same danger(s) on this planet.

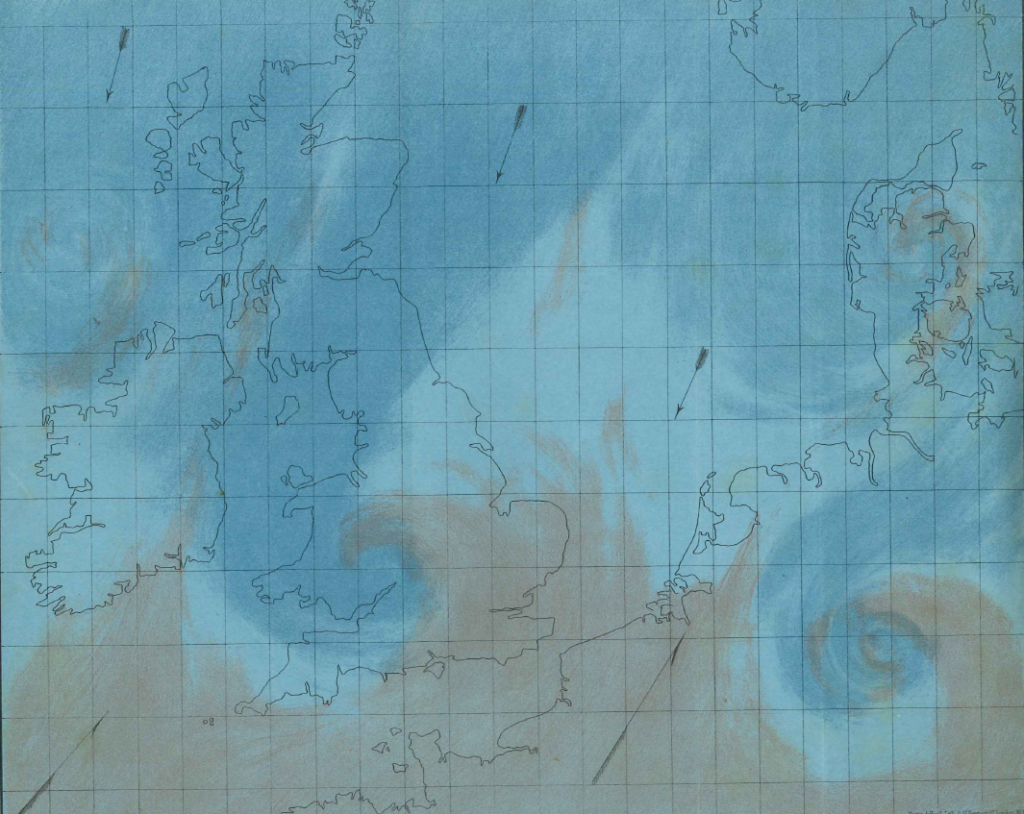

Fitzroy’s illustration of the Air Currents over the British Isles. From Robert Fitzroy, The Weather Book: a manual of practical meteorology, 1863.

Edy Fung

Edy Fung is a multi-disciplinary artist, musician and curator currently based between Derry and Stockholm. She has worked in the conservation of historical buildings and heritage mainly in County Donegal for three years, after graduating from an MA in Architecture at the Royal College of Art. Working at the interface between the physical and the digital, her practice seeks to understand how our material world is conditioned. These include exploring underlying systems, ecologies, ideologies and technological shifts that are dominating our everyday values. She works with images, videos, sound, text, installation and exhibition-making, treating them as ingredients and tools to test her inquiries and speculations about the present world phenomena.