In 1816, there were no Catholic dioceses in Liverpool. The Roman Catholic Church was divided into four districts: London, Western, Midland and North with Liverpool being in the North. There were few Catholic priests and it was left to laymen to provide churches and living accommodation for priests. A group of laymen formed the Society of St Patrick (also mentioned above in Site 2) to establish a Catholic church in the south end of the city.

In 1816, there were no Catholic dioceses in Liverpool. The Roman Catholic Church was divided into four districts: London, Western, Midland and North with Liverpool being in the North. There were few Catholic priests and it was left to laymen to provide churches and living accommodation for priests. A group of laymen formed the Society of St Patrick (also mentioned above in Site 2) to establish a Catholic church in the south end of the city.

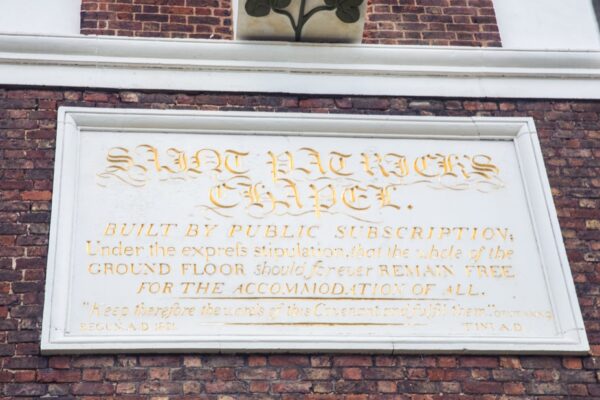

Financial assistance was provided by Anglican and non- conformist churches, as well as local Roman Catholics. St Patrick’s Chapel was built with a large ground floor that would be perpetually freely accessible to the poor at no charge. This pledge is still displayed on a plaque on the outside of the church. The upstairs gallery held 600 people. Those seated here were expected to pay a donation for the privilege, which contributed to the upkeep of the church and the support of its priests. In return, they held decision- making powers.

While the outside of the church is relatively plain, inside a beautiful painting, by Flemish artist Nicaise de Keyser, hangs over what was once a magnificent altar, which stood at the top of seven stairs, surrounded by a brass railing. We say ‘once magnificent’, as the original alter was extremely high church and has been considerably altered since its original installation. St Patrick’s Church are working to reinstate something close to the original in the coming years.

The church was built with a large crypt for a vault. Pit graves lay to the side of the church. Records show at least 7,466 people were interred between 1827-1841. Later burials (bar four noted, shortly) do not appear to have been officially recorded. Dr Duncan (1805-1863) -writing in 1848 about the need to close overcrowded graveyards- records that while the average number of bodies interred in a single pit in St James’s was 30, at St Patrick’s the number was 120.

The foundation stone for St Patrick’s was laid in 1821. It took six years to build and the opening took place on 22 Aug 1827.

The land for the church was provided on a 5,000-year lease, such was the confidence in those securing the site. A large statue of St Patrick, donated by a Dublin insurance company, was placed on a plinth high up in front of the church, the first Catholic statue openly displayed in England since the Reformation.

The long history of interconnectedness and migration between Liverpool and Ireland over the centuries was amplified during The Great Hunger, with many immigrants of the era being ‘paupers’, in a poor state of health. The population of court dwellings swelled in this period; in Crosbie Street (off Park Lane), the population grew from 975 people living in 145 houses in 1789 to 1,544 people in 1851. The boarded-up cellars were illegally re-opened as immigration increased the need for dwelling places. The high death rate among the population -from typhus fever in the overcrowded city- included doctors, nurses, relief officers and priests. Though other official records for burials at St Patrick’s after 1841 are scant, three priests from the parish and one Christian brother were certainly buried in the crypt in 1847. Priests, attending to their sick and dying parishioners, would have been exposed to the disease and many died as a result.

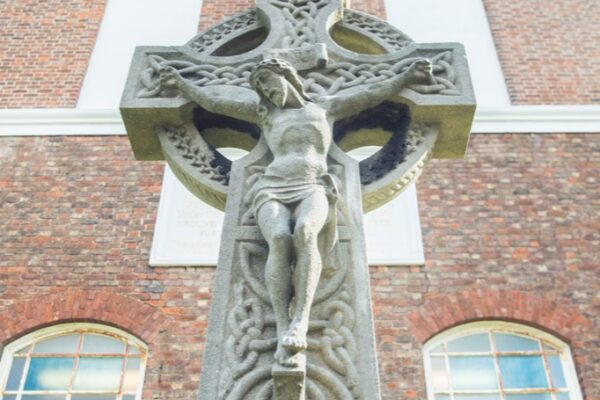

Ten city priests, who died of typhus in 1847, are commemorated on the Celtic Cross in front of the church. They are Rev Peter Nightingale of St. Anthony’s, March

2; Rev William Parker of St Patricks, April 27; Rev Thomas Kelly DD^ of St. Joseph’s, May 1; Rev James Appleton DD OSB^^ of St. Peter’s, May 26; Rev John Austin Gilbert OSB of St Mary’s, May 31; Rev Richard Grayston of St Patrick’s, June 16; Rev James Hagger of St Patricks, June 23; Rev William Vincent Dale OSB of St. Mary’s, June 26; Rev Robert Gillow of St Nicholas’s, Aug. 22 and Rev John Feilding Whitaker of St. Joseph’s, Sept. 18.

^ DD: Doctor of Divinity

^^ OSB: Ordo Sancti Benedicti/ Order of St Benedict. This is a Roman Catholic monastic order, begun in the sixth century. Those belonging to this order are known for liturgical worship and scholarly pursuits. St Benedict (480- 547 AD) is known as the Patron Saint of Europe.

One witness, writing at the time, recalls “I can remember a messenger coming to the pro-Cathedral and saying hurriedly ‘For God’s sake, will some of you come to St Patrick’s and bury the dead. The church is full of corpses and all the Priests are now down. The dead and the dying are lying together and the little children, soon to whither in the Black Death, played with the shavings on which they lay. St Patrick’s church was closed, the Presbytery door stood open, but there was no priest within and when Sunday came, silence reigned around the altar”.