A payment scheme about the financial payments and health support for those who spent time in Mother and Baby and County Home institutions in Ireland.

A payment scheme about the financial payments and health support for those who spent time in Mother and Baby and County Home institutions in Ireland.

Jean Maskell's The Space Between is a book to browse, including paintings and poems, stories and yarns that speak of diaspora experiences.

Liverpool’s cultural ties with Ireland come to the fore once again as the Liverpool Irish Festival returns, this year with special performances by The Guilty Feminist (in a dedicated festival podcast) and Kíla. We also celebrate a new partnership with Liverpool Literary Festival, the return of the Celtic Animation Film Festival and IndieCork and a new play by Lizzie Nunnery.

Taking place 18-28 Oct 2018 in venues across Liverpool, including Liverpool Everyman and Playhouse, FACT, Liverpool Philharmonic, St George’s Hall, the Florrie and the Victoria and Gallery Museum, the programme, curated by Festival Director Emma Smith and partners, explores the theme of ‘migration’. Artists, performers, musicians, writers and filmmakers explore the relationship between cultural identity and place and how Irish identity, in particular, is changing globally, affecting how we understand ‘Irishness’ in the 21st century.

The hugely successful podcast (30m+ downloads), The Guilty Feminist, comes to Liverpool Irish Festival as part of its In:Visible Women programme and for its first visit to the city. Comedian Deborah Frances-White records a live podcast in front of an audience at Liverpool Playhouse, discussing 21st century feminism and the paradoxes and insecurities which undermines it.

One of Ireland’s greatest music acts, Kíla, come to Liverpool Arts Club for a tub-thumping, rip-roaring, freewheeling jig of a gig. Supported by Bill Booth, Kíla’s eight members come from different musical backgrounds, including trad, classical and rock, which blend into the bands furiously energetic sound. It bristles with energy and passion and will be an unforgettable night.

At the Everyman Theatre, Lizzie Nunnery presents her new play with songs, To Have to Shoot Irishmen, exploring the events around the death of Francis Sheehy Skeffington during the Easter Rising in Dublin, 1916. Directed by Gemma Kerr (Hitting Town, Southwark Playhouse) and produced by Lizzie Nunnery’s Almanac Arts, the play runs for three nights (25-27 Oct).

For the first time, Liverpool Irish Festival unites with Liverpool Literary Festival, celebrating the writers, both emerging and established, who continue Ireland’s rich literary heritage. Events include Eamonn Hughes’ fascinating exploration and reflection on his work with Van Morrison, navigating the songwriter’s representation of Belfast. This is a joint event with The Institute of Irish Studies.

At one of Liverpool’s newest venues, OUTPUT Gallery, an artist will create a new work responding to the successful repeal of the Eighth Amendment of Ireland’s Constitution, granting new body autonomy in Ireland. The exhibition will run for the duration of the festival part of the In:Visible Women strand.

As regular readers will know Cara Sanquest of the London-Irish Abortion Rights Campaign introduced the Liverpool Irish Festival to this organisation and to the Abortion Support Network (see Mara Clarke’s piece, here). Cara also introduced us to Hannah Little, a London-Irish Abortion Rights Campaigner, from the Republic of Ireland. Here, Hannah tells us a little about how she became involved ahead, of her speaking at the In:Visible Women day (more details below).

* * * * *

The truth is I never really felt Irish until I left. Growing up I had not considered how my long red hair, thick Dublin accent and chatty demeanour would qualify me as a walking Irish stereotype. When I moved to London I learned the significance of my nationality in encounters with new friends and colleagues. What I saw simply as my personal characteristics – being friendly, sociable and a little forthright – others viewed as typical traits of “the Irish”. I was happy to discover that we were generally viewed quite positively. Before long, I became comfortable with the feeling that I embodied the idea that Ireland was a nation of lively, approachable people.

This new-found national pride was called into question when I heard about the death of Savita Halappanavar in 2012. Savita, a 31-year-old woman from Galway, had died from complications arising from a septic miscarriage after being denied an abortion. Following repeated requests for a termination, her husband and family were told it was not an option “because Ireland is a Catholic country”.

I felt the urge to gather with others and mourn her shocking and tragic death. Lighting a candle outside the towering grey Irish embassy in Knightsbridge, I was forced to reconsider the positive image of Ireland I was promoting abroad. If abortion is recognised as basic healthcare around the world, how could an otherwise healthy woman die in hospital in my home country? The enduring influence of Catholicism in Ireland had suppressed medical wisdom and as a result, Savita had died an entirely preventable death.

As support for a referendum on the issue of abortion in Ireland began to gather momentum, I decided that rather than watching from afar I would try to play my part abroad. In 2016 I was part of a team of Irish ex-pats who organised a London solidarity event on the day of the March for Choice in Dublin. Hundreds gathered outside the Irish embassy to send a clear message that the diaspora were also calling for a full repeal of the eighth amendment – a constitutional change that could enable increased access to abortion in Ireland.

I met a group of likeminded people that day and together we went on to form the London Irish Abortion Rights Campaign. Since then, our group has grown to over 1,500 members and boasts a team of over 60 volunteers working on a daily basis. We campaign for access to free, safe and legal abortions across the island of Ireland through fundraising, direct action, lobbying of politicians and building international awareness of the issue through the UK media.

With a referendum on the Eighth Amendment now imminent, the next few months are crucial for the Irish pro-choice movement. As we saw with the result of the referendum on same sex marriage, Ireland is ready to break free from Catholic conservatism and adopt the twenty-first century values of inclusiveness and acceptance.

Irish people do not need to identify as pro-choice to appreciate that current legislation is harming Irish women*. The United Nations has repeatedly stated that Ireland is in breach of human rights by denying its citizens access to basic healthcare. I hope that by voting for increased access to abortion, Ireland can go some way to redressing the tragic injustice of Savita’s death and no doubt countless others.

Only when Ireland allows women to have full control over their own bodies will I be proud to call it home again.

(*) trans, and non-binary people

The London-Irish Abortion Rights Campaign calls for the repeal of the 8th amendment from the Irish constitution (ROI) and campaigns for access to free safe legal abortion in Ireland and Northern Ireland. They are the London branch of the Abortion Rights Campaign in Ireland, and a member of the Coalition to Repeal the 8th Amendment. londonirisharc.com | repealeighth.ie | abortionrightscampaign.ie Handles: /londonirisharc /ldnirisharc

Abortion Support Network provides financial assistance and accommodation to those travelling from the Republic of Ireland, Northern Ireland and the Isle of Man for abortion procedures. Funding is available on a case by case basis, depending on financial need and availability of funding. Individuals are asked to contact ASN before booking travel as they can also advise on the least expensive clinics and methods of transport. ASN provide confidential, non-judgmental information to anyone who contacts them via phone or email about travelling to England for an abortion, as well as information about reputable providers of early medical abortion pills by post, which they also provide information on. asn.org.uk Press and non-urgent enquiries can be made to Mara Clarke, Founder and Director of ASN here:

Mara Clarke at [email protected] + 44 (0) 7913 353 530.

In:Visible Women takes place on Fri 27 Oct 2017, as part of /LivIrishFest at Central Library. Book tickets here:

https://www.liverpoolirishfestival.com/events/invisible-women-illuminating-debates/

What is a wife without a child? Incomplete? Worthless? Childless – or childfree?

In rural Ireland in the 1950s such a woman would almost certainly have been scorned as “barren” and her husband would have been within his rights to pack her bags and send her back to her family in disgrace.

This is the cultural background to a new play Body and Blood, which premieres at the Liverpool Irish Festival in October 2017. Here, the writer, Lorraine Mullaney explains how she came to write the play.

* * * * *

“She’s no good to me now,” said Bridie Keenan’s husband, as he returned his “barren bride” to her parents. “No farmer wants a barren wife. I have two sisters in the house to feed already.”

Poor Bridie. Sent home in disgrace to face the humiliating status of “barren bride”. But, instead of rebuking Bridie’s husband for his cruelty – or blaming him for his own lack of fertility – the local gossips in the Post Office blame the bride’s parents.

“They waited till she was 30 before making a match for her. Matches should be made when the girls are young,” they say. “Then there’s plenty of time to make a good family. If Bridie’s parents didn’t have the dowry, they should have sent her away to find work.”

* * * * *

This harsh reality forms the lives of the characters in Body and Blood. The play is set in 1956, a time when many marriages in rural Ireland were still arranged by matchmakers and the girls matched to local farmers from the age of 15 onwards. Irish farmers often deferred marriage until they were well on in years so they needed much younger wives to bear them sons to work on the farm and inherit the land to keep the family name alive.

The family of the bride entered a discussion process, organised by the matchmaker, in which dowries were balanced against the land and livestock of the potential groom. A ritual called “the walking of the land” was part of the process. In this ceremony, the groom walked the father of his desired bride around his land to show him what he had to offer his daughter through marriage. Once the dowry and cattle had been negotiated and the match agreed, they would mark the occasion with a celebratory meal, for which geese would be slain and whiskey and porter bought.

Once married, the girls often found themselves living on remote farms with animals to be fed, bread to be baked, bacon to be boiled, cattle to be milked, and turf to be cut. All amidst the driving rain and – if you’re living on the side of the mountain as the characters are in Body and Blood – the relentless rolling mist.

It’s not surprising that travelling to England became an attractive prospect for some girls. Body and Blood tells the story of a young Irish girl, Aileen, who comes to London in 1956 searching for her runaway sister, who fled rural Ireland to escape an arranged marriage to a man with “a face like the Turin Shroud”. But, instead of finding her runaway sister, Aileen finds new freedom in London and a romance with Jimmy. Which way will she turn? Will duty win over desire?

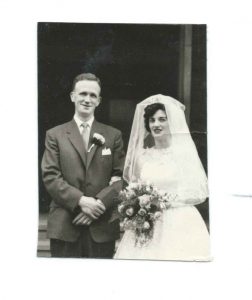

Image: The author’s parents on their wedding day, London 1960.

Image: The author’s parents on their wedding day, London 1960.My mother also came to London in the late 1950s from County Cavan, and one of her stories was the inspiration for this play. She loved the West End, where she worked as a chambermaid in the hotels, until she met my father, from County Sligo, and they got engaged. My parents married in London in 1960. No dowries or cows exchanged hands.

When my father’s mother came over from Ireland to meet her new daughter-in-law, she didn’t approve of the engagement. She told my mother: “I came to my marriage with a dowry and cows but you’ve come to yours empty-handed.”

My mother told me this story when I was a child and I found it shocking. Growing up in 1970s London – in a Reggie Perrin-style suburb of 1930s semis and men in navy blue suits catching the 7.57 to Waterloo – it felt like a story from centuries past, or a distant culture on the other side of the world. How could a country that was so close in distance be so far away in culture?

The author’s parents on their wedding day, London 1960.

The author’s parents on their wedding day, London 1960.Irish matches were designed to keep the land in the family name and they were very much a product of their time: an era when duty to land, family and country came before personal freedom. They weren’t necessarily forced marriages and returning so-called “barren brides” to their families was at the most brutal end of the spectrum. At the other end must surely have been many happy marriages, perhaps with more realistic expectations than those with more romantic beginnings. And some of today’s methods of meeting a likely partner have their own brand of brutality with their snap judgements and swipe-and-reject culture.

When I was promoting a shorter, earlier version of this play in North London over the summer, I handed a flyer to an Irish girl who was sitting outside a pub on Upper Street, Islington. We got chatting about how far Ireland has come since the days of arranged marriages – or matches. Finally, she laughed: “I wish they still had arranged marriages at home. Trying to find a man in London is a nightmare. I need all the help I can get.”

If you have a story about arranged marriages you’d like to share, contact Lorraine on [email protected]. Lorraine will collate the stories gathered as research for a book. Your story will not be published without your express permission.

Body & Blood – by Lorraine Mullaney is – presented by Unclouded Moon Productions at the Liverpool Irish Festival, co-produced with Sorcha Brooks. Mon 23 Oct and Tues 24 Oct 2017, 7.30pm followed by Q&A with the cast and writer, at The Capstone Theatre, 17 Shaw Street, Liverpool L6 1HP. Tickets at £12/£10 + booking fee. Ticket line (freephone): +44 (0) 844 8000 410

About arranged marriages in Ireland

Arranged marriages in Ireland continued well into the 1970s. The brides’ dowries were balanced against the land and livestock of the men they were matched with. Marriages were arranged by matchmakers and the girls could be as young as 15. Irish farmers often deferred marriage until they were well on in years so they needed much younger wives to bear them sons to inherit the land and keep the family name alive. A matchmaking festival held during the month of September in Lisdoonvarna, County Clare on the west coast of Ireland has been running for over 150 years (more info here).

About Unclouded Moon Productions

Unclouded Moon Productions develops and produces new plays that tell stories about ordinary people in extraordinary situations. The plays explore universal themes in a way that is entertaining, engaging, and thought provoking, with a particular focus on Irish culture and its impact on the lives and pathways of generations of Irish men and women.

Jane was commissioned by the Liverpool Irish Festival, from artist Alison Little, as a contribution to its work about In:Visible Women. It is a fictional piece of writing, created to help readers consider the effects of sexual violence towards women. Although it will echo some experiences, it is not ‘the definitive story’, nor is it specific to a real individual. We raise this not to diminish its value, but to assure readers that no survivor’s story is being misused. This piece is also supported by an artwork, which will be on show during the In:Visible Women day (Central Library, Fri 27 Oct 2017, £5).

Images of Alison’s art work are used throughout this feature. Featuring the torso of a woman (formed from delicate paper strands, echoing the fragility of womanhood), the shape is held together by clear, surgical plastic. This main shape, through which the womb can be identified, has labels that spill from its sides. These labels indicate the powerful responses a women might consider after a sexual attack, services or choices that may be available or the labels placed upon her by external bodies. These labels are combined, showing how complex the messages are about personal freedoms, service access and support. They include lines such as “clinical violence”, “stigma and silence” and “liberty”. Whether witnessed in a forest or on a gallery floor, the haunting image of this woman, dismembered and left behind, is symbolic of the treatment of women facing difficult questions about their future today.

Due to the sensitive content relayed in the following piece, relating to sexual violence and rape culture, we advise reading on with caution.

Simply Jane

Jane awakens. Her eyes bolt open, so much so it feels as though her upper lashes are laid flat against her eyebrows. The eyes almost detach from their position as the globes project up towards the ceiling, her pupil’s forefront in their position. Wide awake in panic again from the last eight weeks and four-days since it happened.

Although a chilly night, as they often are in County Cork, she was sweating intensely. Her groin was wet and the undersides of her flowering breasts were drowned in perspiration. She feels down between her legs, wishfully hoping that the damp may be ‘Me Auntie Bid’ finally arriving, six weeks and approximately three days late. She could only feel perspiration, no thicker substance, her optimism fades away as she faces the reality of being with child.

Still anxious, twisted in her bodily position, she begins to think about it again; what happened on that ill-fated night eight weeks and four days ago. She was at a sixteenth birthday party, not far away, just the next village. It was her best friend’s shindig, they had all brought what beer, cider and wine they could get hold their hands and one of the travellers had jigged in with a bottle of Poitín.

In her innocence Jane had got tipsy on the drink, then tipsier, finally slipping into inebriation. One of the older fellas had been dancing with her. She didn’t really know who he was, he must have been from a village in the opposite direction. As she became a little stilted in her motion, he placed his hands on her hips, then guided her towards the open front door. As the cold air had hit her she began to sober up. On his suggestion they went to sit in the barn.

As they sat on some crates he began to tell her she was a ‘Wee Doll’ and how the blue of her dressed matched her eyes. After brushing his wet lips quickly across hers he produced an unopened half bottle of Jameson’s. He opened the lid and took a quick swig before passing it over to Jane: ‘Come on have some’, enticing her into becoming drunk again.

The next thing Jane can remember is that he is on top of her, back flat against the concrete as he fumbles around her dress as he tries to remove her knickers. Jane tries to squirm and say no but he pushes himself into her, she can’t move as he protrudes into her virginal body.

After he had finished, he moved to one side and appeared to fall into a drunken slumber. Jane manages to stand slowly, edging out of the barn, away from the light and noise from the party, down long country lanes, bushes each side, moon half visible, night owls coo-ing in the distance, to her village, her front door, her room, bed, her fear.

…Article continues after the slide show…

She lies in that bed tonight, thoughts rushing through her mind about her one sexual encounter. The one she had not wanted and the one which had left her bearing child. She tosses over in bed again, her mind engulfed with thoughts about how to end this ordeal.

Abortion pills? She could order online, but are they safe? What if she gets caught having them delivered? It was such as small village, the Post Man knew everybody and the Post Mistress was always chin-wagging and may even open the package.

Her parents finding out seemed bad enough, but she could even be locked up by the Garda. She could travel to England or the Netherlands; a cheap flight from Ryanair could get her to Amsterdam. Can she get enough money for the operation?

She had no-one to talk to. Her friend who had sprung the party had found her knickers and the barn and all the girls at school seemed to know that something had happened, she felt like they were calling her a ‘Floosie’.

She wanted a ‘babby’ one day. It was his baby she didn’t want. Every day she lived in fear of seeing him again, smelling him again. Even the remnants of her Dad’s malt from his glass brought on the urge to vomit now. The vision of him and the memory of her inability to move as he forced into her innocent body… She thinks of how this baby would remind her of him. It could grow up to look like him, possibly even act like him.

She turns in bed again. She had no choice. She couldn’t have this baby, but how and when could she terminate the pregnancy? An owl, outstretched, screeches in the distance. She envisages the black eternity of the sky under its expanse the owl looking down on her as a minuscule speck; alone amidst the wrongs of the World which make up human existence.

Services and support

If you have been affected by the contents of this piece, please consider consulting one of the services below:

Rape and Sexual Abuse Centre (RASA) – this is a Mersey based support service, rather than a national service. Please see below for more on wider support services rasamerseyside.org +44(0) 151 666 1392; [email protected] If using email, please be mindful of the security of your account and other people’s access to it.

NHS – Sexual assault and violence services are available in most UK cities. To help to locate a service near you, the NHS have a service locator, which you can access using this webpage (successfully accessed 18 Sept 2017): http://www.nhs.uk/Livewell/Sexualhealth/Pages/Sexualassault.aspx

Abortion Support Network – if you – or a friend – requires access to abortion support services from Ireland, Northern Island or the Isle of Mann, the Abortion Support Network may be able to assist – asn.org.uk To call from Northern Ireland +44(0)7897 611 593; from Ireland +44(0)15267370 (calls only, no texts) and/or from the Isle of Man +44(0)7897 611593 or email [email protected] If using email, please be mindful of the security of your account and other people’s access to it.

Victim Support can offer assistance with how to handle reporting a crime as well as helping you through the legal procedures of pursuing a charge. For more details of how to use these particular services, use this link https://www.victimsupport.org.uk/crime-info/types-crime/rape-sexual-assault-and-sexual-harassment (successfully accessed 18 Sept 2017).

If you are supporting someone you know to have survived a violent, sexual encounter, there are some interesting and useful points in this online article, from The Everyday Feminist (successfully accessed 18 Sept 2017): https://everydayfeminism.com/2013/01/how-to-help-sexually-assaulted-friend/

This is not an exhaustive list of services available or resources you can access, but we hope it may serve as a start point, where needed, for anyone experiencing, supporting or hoping to assist.

About the artist

Alison Little is an artist based in Anfield in Liverpool. She has also worked on a number of large scale commissions including Go Superlambanana, Go Penguin, Cheltenham Horse Parade and more recently the Nottingham Biennial. Smaller works are available to purchase from Arts Hub 47 on Lark Lane. Alison says: “I was conceived an artist and have spent the moments since birth developing my practice, something which will continue throughout my life”. You can find out more about Alison and Arts Hub 47 using this link.

The Liverpool Irish Festival would very much like to thank Alison for these two revealing, compassionate and sensitive pieces of work. From a random email out of the blue and through just a few interactions, the development of these pieces has been fast, informative and activated. Thank you Alison.