#LIF2023 Chair and musician, John Chandler, takes readers through the trad sessions avaiable across Liverpool (Aug 2023).

#LIF2023 Chair and musician, John Chandler, takes readers through the trad sessions avaiable across Liverpool (Aug 2023).

We asked long-standing Liverpool Irish Festival friend Gerry Ffrench to give us some information on her roots and current work, ahead of a performance of self-penned music and songs over at the Albert Docks for the Three Festivals Tall Ships Regatta (the late May bank holiday weekend 2018).

Gerry has sung in festival sessions and in 2017 played Master of Ceremonies for our Visible Women evening, over at the Philharmonic Music Room, introducing Emma Lusby, Mamatung, Sue Rynhart and Ailbhe Reddy. We regularly talk about the books that Gerry has planned, stories from her father’s life and the incredible influence of Irish history of Liverpool life.

Gerry is the winner of Folk Northwest’s talent showcase, which took place at Costa del Folk Portugal in 2017. A singer songwriter from Liverpool, Gerry has strong family links in Wexford and Mayo. She is a popular performer in folk clubs in and around Merseyside – and the North of England – as well as appearing at various folk and shanty festivals here and abroad. Currently working on her third full studio album of original songs in Angel Valve Studios Oxton (Birkenhead), Gerry uses the stories of ordinary people of the city – past and present – as an endless source of inspiration for her songs.

Gerry’s new album, Rivercity Echoes, runs as a succession of stories, intertwining Irish and Liverpool life. Rivercity Echoes will have eleven original tracks, all composed, sung and played by Gerry with almost every track telling a story. Through these stories, Gerry speaks of times gone, of love and loss and of today. Below is a breakdown of those stories, as described by the artist.

When Paddy Came Marching Home is about a whacky Irishman who in 1939 joined the Royal Navy, didn’t like it, so enlisted in the army while on leave, eventually fighting his way from North Africa all the way to Germany.

Do Your Washing for a Penny was inspired by the great Liverpool Irish philanthropist Kitty Wilkinson*, originally from Derry, who was instrumental in setting up wash houses in the slums of the city, after saving many lives during the cholera epidemic of the 1830’s.

* #LIF2018 features a play on this subject, by Carol Maginn called Kitty. To keep up to date with our programme (announced from summer), sign up to our mailing list. We usually send no more than one mail per month, rising nearer to the festival with event news. We never sell any data.

The Admiralty Regrets is the half-forgotten story of the Thetis Submarine disaster in Liverpool Bay. It was triggered by seeing 99 men’s names on the steps of the bell tower in Birkenhead Priory, right next to Camel Laird’s where the sub was built in 1939.

I wrote My Brother’s Shoes after seeing a pair of combat boots, left by a veteran, at the Vietnam War Memorial in Washington DC seven years ago.

Dorothy Drew retells the story a popular traditional folk song The Callico Printer’s Clerk – from the point of view of the female protagonist.

Bound For Glory was written after a fan suggested I check out the history of the Isle of Mann Packet ship The Ben Ma Chroidhe, which sank off the coast of Turkey during the first wold war.

And so it goes, although not all of my songs are about the past, I – like Santayana – believe that “Those who cannot remember the past are doomed to repeat it.”

The Liverpool Irish Festival would like to thank Gerry for giving this exclusive insight in to her new album! What a treat for us! To find out more and to keep up with Gerry’s album release make sure to follow her on Facebook, search for “Gerry ffrench, Folk Singer” or visit her site: http://gerry.helloplaza.uk/

What is a wife without a child? Incomplete? Worthless? Childless – or childfree?

In rural Ireland in the 1950s such a woman would almost certainly have been scorned as “barren” and her husband would have been within his rights to pack her bags and send her back to her family in disgrace.

This is the cultural background to a new play Body and Blood, which premieres at the Liverpool Irish Festival in October 2017. Here, the writer, Lorraine Mullaney explains how she came to write the play.

* * * * *

“She’s no good to me now,” said Bridie Keenan’s husband, as he returned his “barren bride” to her parents. “No farmer wants a barren wife. I have two sisters in the house to feed already.”

Poor Bridie. Sent home in disgrace to face the humiliating status of “barren bride”. But, instead of rebuking Bridie’s husband for his cruelty – or blaming him for his own lack of fertility – the local gossips in the Post Office blame the bride’s parents.

“They waited till she was 30 before making a match for her. Matches should be made when the girls are young,” they say. “Then there’s plenty of time to make a good family. If Bridie’s parents didn’t have the dowry, they should have sent her away to find work.”

* * * * *

This harsh reality forms the lives of the characters in Body and Blood. The play is set in 1956, a time when many marriages in rural Ireland were still arranged by matchmakers and the girls matched to local farmers from the age of 15 onwards. Irish farmers often deferred marriage until they were well on in years so they needed much younger wives to bear them sons to work on the farm and inherit the land to keep the family name alive.

The family of the bride entered a discussion process, organised by the matchmaker, in which dowries were balanced against the land and livestock of the potential groom. A ritual called “the walking of the land” was part of the process. In this ceremony, the groom walked the father of his desired bride around his land to show him what he had to offer his daughter through marriage. Once the dowry and cattle had been negotiated and the match agreed, they would mark the occasion with a celebratory meal, for which geese would be slain and whiskey and porter bought.

Once married, the girls often found themselves living on remote farms with animals to be fed, bread to be baked, bacon to be boiled, cattle to be milked, and turf to be cut. All amidst the driving rain and – if you’re living on the side of the mountain as the characters are in Body and Blood – the relentless rolling mist.

It’s not surprising that travelling to England became an attractive prospect for some girls. Body and Blood tells the story of a young Irish girl, Aileen, who comes to London in 1956 searching for her runaway sister, who fled rural Ireland to escape an arranged marriage to a man with “a face like the Turin Shroud”. But, instead of finding her runaway sister, Aileen finds new freedom in London and a romance with Jimmy. Which way will she turn? Will duty win over desire?

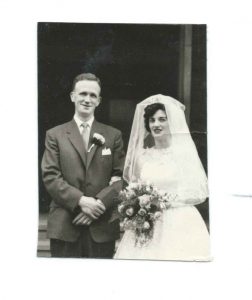

Image: The author’s parents on their wedding day, London 1960.

Image: The author’s parents on their wedding day, London 1960.My mother also came to London in the late 1950s from County Cavan, and one of her stories was the inspiration for this play. She loved the West End, where she worked as a chambermaid in the hotels, until she met my father, from County Sligo, and they got engaged. My parents married in London in 1960. No dowries or cows exchanged hands.

When my father’s mother came over from Ireland to meet her new daughter-in-law, she didn’t approve of the engagement. She told my mother: “I came to my marriage with a dowry and cows but you’ve come to yours empty-handed.”

My mother told me this story when I was a child and I found it shocking. Growing up in 1970s London – in a Reggie Perrin-style suburb of 1930s semis and men in navy blue suits catching the 7.57 to Waterloo – it felt like a story from centuries past, or a distant culture on the other side of the world. How could a country that was so close in distance be so far away in culture?

The author’s parents on their wedding day, London 1960.

The author’s parents on their wedding day, London 1960.Irish matches were designed to keep the land in the family name and they were very much a product of their time: an era when duty to land, family and country came before personal freedom. They weren’t necessarily forced marriages and returning so-called “barren brides” to their families was at the most brutal end of the spectrum. At the other end must surely have been many happy marriages, perhaps with more realistic expectations than those with more romantic beginnings. And some of today’s methods of meeting a likely partner have their own brand of brutality with their snap judgements and swipe-and-reject culture.

When I was promoting a shorter, earlier version of this play in North London over the summer, I handed a flyer to an Irish girl who was sitting outside a pub on Upper Street, Islington. We got chatting about how far Ireland has come since the days of arranged marriages – or matches. Finally, she laughed: “I wish they still had arranged marriages at home. Trying to find a man in London is a nightmare. I need all the help I can get.”

If you have a story about arranged marriages you’d like to share, contact Lorraine on [email protected]. Lorraine will collate the stories gathered as research for a book. Your story will not be published without your express permission.

Body & Blood – by Lorraine Mullaney is – presented by Unclouded Moon Productions at the Liverpool Irish Festival, co-produced with Sorcha Brooks. Mon 23 Oct and Tues 24 Oct 2017, 7.30pm followed by Q&A with the cast and writer, at The Capstone Theatre, 17 Shaw Street, Liverpool L6 1HP. Tickets at £12/£10 + booking fee. Ticket line (freephone): +44 (0) 844 8000 410

About arranged marriages in Ireland

Arranged marriages in Ireland continued well into the 1970s. The brides’ dowries were balanced against the land and livestock of the men they were matched with. Marriages were arranged by matchmakers and the girls could be as young as 15. Irish farmers often deferred marriage until they were well on in years so they needed much younger wives to bear them sons to inherit the land and keep the family name alive. A matchmaking festival held during the month of September in Lisdoonvarna, County Clare on the west coast of Ireland has been running for over 150 years (more info here).

About Unclouded Moon Productions

Unclouded Moon Productions develops and produces new plays that tell stories about ordinary people in extraordinary situations. The plays explore universal themes in a way that is entertaining, engaging, and thought provoking, with a particular focus on Irish culture and its impact on the lives and pathways of generations of Irish men and women.

Liverpool Irish Festival returns for its 15th year this October.

Liverpool Irish Festival is the only arts and culture led Irish festival in the UK platforming an incredible array of art, culture, performance, film, music, literature, food and drink, talks and tours

It runs for 10 days between Thurs 19-Sun 29 October 2017 at venues including the Liverpool Philharmonic Music Room, the Capstone Theatre, Liverpool Irish Centre, Handyman Supermarket, Liverpool Central Library and more

It’s returning for its 15th year and involves hundreds of artists and performers

Expanding on previous festival events, In:Visible Women delivers a new strand of festival work exploring gender politics in Liverpool and Ireland’s history and culture, including a talk by BBC war correspondent Orla Guerin (in partnership with the Institute of Irish Studies at University of Liverpool); photography from Casey Orr, children’s author Carmel Kelly and others.

Liverpool Irish Festival returns for its 15th year asking, “what does it mean to be Irish?” 2017 is a significant year for Irish culture and identity. With the potential impact of new Irish citizens applying for passports; a review of Ireland’s Global Diaspora and referendum policies plus the election of Taoiseach Leo Varadkar, a growing conversation on the future of the island of Ireland and its relationship between “traditional values” and 21st century liberalism is surfacing. In its role as the largest festival of Irish arts and culture in the UK.

Liverpool Irish Festival is well placed to invite artists, academics and the public to explore these conversations and how the relationships between Ireland, Liverpool and the wider UK will develop at this critical juncture.

Highlights of the 2017 festival include:

**BBC War Correspondent Orla Guerin reflects on a frontline career a broadcast journalist, experiencing some of the most unsettled war zones in the world. Orla’s lecture launches a new festival strand In:Visible Women, which explores some of the ‘forgotten women’ from Liverpudlian and Irish history, as well as contemporary issues facing women. This precedes a night of music from Liverpool and/or Irish female performers, including folk musician, Liverpool resident and Comhaltas player, Emma Lusby (Limavady, Co Londonderry); vocalist and composer Sue Rynhart and singer Ailbhe Reddy (both Dublin).

**Festival bands include Strength NIA (Derry) and Seafoam Green (Dublin). Live sessions take place in pubs across the city and a three-night festival club at Liverpool Philharmonic’s Music Room.

**Full performances of the play ‘Committed’. Having first appeared as a script-reading at Liverpool Irish Festival 2014 it returns after a successful run. Written by Stephen Smith (Belfast), the play is set in 1990s Belfast, against the backdrop of the peace process and continuing aggression and violence within communities.

**‘The Lily and the Poppy’, a strand of work (and name given to the festival’s partnership with the Institute of Irish Studies, University of Liverpool) first launched in 2016, returns with a talk exploring reconciliation, particularly within Ireland.

**A new Liverpool Irish history book by Greg Quiery (musician, walking tour-guide, writer and Liverpool Irish Festival Board member) launches at the festival, offering a definitive examination of the indelible historic and cultural bonds between Irish communities and “East Dublin”, as Liverpool is often known. The launch is sponsored by, and will take place at the, Institute of Irish Studies.

Emma Smith, Festival Director says,

“Over the past 15 years the Liverpool Irish Festival has worked towards becoming the only arts and culture led Irish festival in the UK. Our consideration of contemporary arts practice, Irish culture and some of the more traditional elements of Ireland’s creative expression, permit us to engage in both current and historic stories that tie Liverpool and Ireland together. Because we have created and programmed a multidisciplinary festival, we offer the opportunity of hearing from a range of voices, providing the chance to hear these stories through written form, voice, music, song, dance, art, and performance. There are opportunities to speak with the artists, watch their work from a distance or engage directly. This leads audiences to a rich variety of events, practices and spaces. We have more exciting projects to announce for this year’s festival and we think it’ll be our most diverse and exciting yet!”

The full programme will be online to book tickets at www.liverpoolirishfestival.com from Mon 11 Sept 2017

Facebook, Twitter & Instagram search for LivIrishFest

#madfortrad

#madfornew

#invisiblewomen

#LivIrishFest

The most diverse celebration of Irish culture in the UK, Liverpool Irish Festival began in 2003. Established to celebrate cultural connections between Liverpool and Ireland, bringing the two communities closer together through arts and culture, the festival has grown into a ten day festival of music, art, performance, culture, food, drink and film. Key artists to have performed at the festival include: Roisin O, Ciaran Lavery, Fearghus O’Conchuir, Terri Hooley, Ailís Ni Rhian, Lisa Hannigan and Dennis Connolly and Anne Cleary (2015’s Meta Perceptual Helmets). Liverpool Irish Festival works with partners across the city and Ireland including the Liverpool Irish Centre, Irish in Britain, Connected Irish, NML, Liverpool Philharmonic, the Unity, the Capstone and the Irish Embassy along with other social spaces such as The Caledonia, Kelly’s Dispensary and The Edinburgh.

The Liverpool Irish Festival is supported with Cultural Investment funding from Liverpool City Council, for which it is greatly indebted.

Following conversations between Chris Kelly and the Liverpool Irish Festival, it was apparent that Chris’s knowledge of music was deep and bountiful. In the spirit of offering context to Irish culture and to increasing general understanding about its origins, pathways and future, Chris has drafted a short history on traditional Irish music, which we hope will give people some food for thought, names to look up and a context for why it is still so important to Irish communities today, not to mention its incredible impact on popular music around the world!

Traditional Irish music began as an oral tradition, passed down from generation to generation by listening, learning by ear and without writing the tunes down on paper. This practice is still encouraged to this day.

The traditional music played by the Irish came to Ireland with the Celts 2,000 years ago. The Celts were influenced by music from the East and, it is believed, the traditional Irish harp originated in Egypt.

The harp was the most popular instrument in ancient times and harpists were employed to play for the chieftains and to create music for the nobles. This was until ”The Flight of the Earls” in 1607 when the native Irish chieftains fled the land under threat of invaders. With the flight of their patrons to mainland Europe, the harpists were left to travel the country and play wherever they could. The most famous of these was Turlough O’Carolan (b.1670-d.1738) a blind harpist, composer and singer whose great fame is owed to his gift of melodic composition. Although not a composer in the classical sense, he is considered to be Ireland’s national composer. For almost 50 years, O’Carolan journeyed from one end of Ireland to the other, composing and performing his tunes.

Not until 1762 were the tunes written down for the first time and collectors began to travel the country compiling music that can still be viewed today. The largest collection of traditional and folk music in the world is in the Irish Traditional Music Archive in Dublin.

Traditional music has travelled much further than the 32 counties of Ireland. It has travelled around the world with the country’s long history of immigration. It was during the time of the great famine of 1845 that vast numbers emigrated, mostly to the United States, bringing the music with them.

In 1920 Irish music had a revival in the States, when recordings were made for the first time. Michael Coleman’s fiddle recordings were to influence fiddle players in the States, Ireland and around the world for years to come.

The style of music was opened to a wider audience still, due to the influence of Sean O’Riada, who established a traditional ensemble, Ceoltoiri Chulainn, who were heavily influenced by classical music forms. The Chieftians were later formed by Paddy Moloney from that ensemble.

The main traditional instruments are fiddle, Celtic harp, Irish flute, penny whistle, uilleann pipes and bodhrán. More recently the Irish bouzouki, acoustic guitar, mandolin and tenor banjo have found their way into the playing of traditional music, mainly due to Sweeny’s Men and Emmet Spiceland in the late ‘60s, followed by Paul Brady, Andy Irvine, Planxty, De Danann, The Bothy Band, Moving Hearts and many others, too numerous to mention.

There has always been a large Irish community in Liverpool, and the surrounding area, and the music has been passed on from generation to generation through the likes of the original Irish Centre in Mount Pleasant (also known as The Wellington Rooms), with music lessons for all types of traditional instruments. Sadly, that venue closed many years ago, moving to St. Michael’s, just off of West Derby Road. The Irish pub scene appears of late to have had a bit of a resurgence and with folk clubs and pubs like The Caledonia and the annual Liverpool Irish Festival facilitating the ongoing tradition there is great hope of the tradition carrying on for many years to come.

All I can say, after all that is ”keep music live and support the venues that support live music”.

Christopher Kelly – Chris’s early musical influence was The Beatles. He got first guitar at the age of 13 and played in showbands (pop and country) all over Ireland until going to the States in 1969, returning after 6months. Chris came to Liverpool in 1971 and is still here, becoming involved in folk clubs after he and long-time friend John Marshall visited Maghull Folk Club in the early ’70s, mainly playing John Prine, Micky Newbury and Steve Goodman material, later shifting to traditional music. Chris and John have been playing together on and off ever since, despite John’s many years in Scotland and Wales. In these times, Chris has played in various bands including Cairde Ceol (Musical Friends), Cracker, Jig-a-Jig and has done duo work with Tony Gibbons and other solo projects. John returned to Liverpool over a year ago and Chris and John are back together (musically). They have put together a vast collection of traditional songs and tunes in that time, performing as Tippin’ It Up. Chris, John and some other musical friends are recording an album of original material which should be ready in late 2016/early 2017.

Tippin’ It Up are playing at a couple of the social seisiúns at #LIF2016, at the Everyman.

A tension rankles between the traditional vanguard and today’s ‘new wave’. Reflected in culture, multiple understandings of history and our communication choices, the struggle to understand generations before and after our own is often at the root of why we create: to tell our story. In the centenary year of the Easter Rising and the year of Brexit – two defining and connected moments shaping Ireland, Britain and Europe – the tension between new and old is of the zeitgeist.

Tension isn’t necessarily negative. It can be the propellant needed to push beliefs and society forward making new ground and putting pay to outdated thought. Consider last year’s majority vote supporting gay marriage in the Republic of Ireland, a powerfully progressive statement wholly unimaginable at the time of the Eater Rising. It demonstrates we can take something traditional – marriage – and inject it with a contemporary spark – equality! – to create something new, showing tension can create something warm, friendly and downright convivial. We need to celebrate these stories to keep moving forward.

So, what is ‘a story’? Literally, a story is “a narrative designed to interest, amuse, or instruct the receiver”. Stories allow us to understand personal positions; picture individual environments and reflect and share our histories, differences and similarities. They state our identities. Post-Brexit our stories could be more important than ever, which informs what 2016’s Liverpool Irish Festival is about: bringing Liverpool and Ireland closer together. What could be more convivial than that?

Everyman Street Café will provide (Mon-Sat) the social hub for the festival, with a small library of Irish materials, providing space for people to meet, talk about festival events and make friends. The event holds multiple stories ripe for sharing, discussing and reconsidering. A 100 years since James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man HE Ambassador to Ireland Dan Mulhall, Professor Frank Shovlin of the University of Liverpool’s Institute of Irish Studies and other academics will discuss its significance and legacy. Scadán (a new Irish story and production) from Liverpool and Irish writers, actors and producers, explores five female stories on an Irish island, 100 years ago.

Commemorative responses differ across the generations, offering moments of reflection and chances to explore a central moment in the foundation of the Irish Republic. 1916’s Easter Rising saw six days of fighting in Dublin, with nearly 100 men and women risking everything to travel from Liverpool to take part, stating a claim for their Irish-ness. Today 6 million ‘English people’ await Irish passport decisions, showing ‘Irish-ness’ is just as important today. Accordingly, this year, we are showing contemporary works exploring what the Easter Rising means – historically and today – in artefact form (Central Library) and in print (the Bagelry), with additional talks on the subject. Singer songwriter – Damien Dempsey – performs his unique album No Force on Earth commemorating the Rising (Music Room, Liverpool Philharmonic). We also have Peter King’s (descendent of the King Brothers, famous Liverpudlian Easter Uprising volunteers) Liverpool Lambs among many more.

The Liverpool Irish Festival does not pitch new against old. It explores what can be learned from both and enjoys what can happen in between. Without taking sides, it considers how and why we arrive where we are and how we may use it to shape what follows. It provides convivial environments to provoke discussion, encourage sharing and explore difference, whilst building friendships, progressing views and creating positive experiences. Sound interesting? Get along to the Liverpool Irish Festival, 13-23 October 2016.

Written for Bido Lito by Laura Brown and Emma Smith