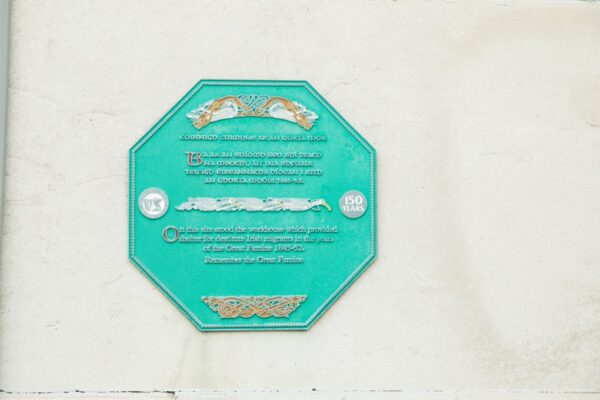

The plaque is located on the side of the Hart Building (part of University of Liverpool), facing The Guild of Students.

The plaque is located on the side of the Hart Building (part of University of Liverpool), facing The Guild of Students.

The first parish workhouse in Liverpool was founded on the corner of College Lane and Hanover Street in 1732. Between 1769 and 1772 a new House of Industry was built at Brownlow Hill, designed to accommodate 600 inmates. By 1790 there were over 1,200 people in the institution.

Men and women were segregated within the workhouse, but there was accommodation for married couples. Inmates were expected to work 12-hour days in the institution, undertaking tasks such as oakum picking (teasing fibres from old ropes) and weaving. From the age of nine children in the workhouse were taught to weave, while also attending school, later becoming bound apprentices to a variety of trades. A chapel was built within the workhouse and there was also a detached building used as a fever hospital, in which female paupers served as nurses. After the Poor

Law Amendment Act 1834, the select vestry became responsible for the workhouse. This continued until 1922 when the vestry was disbanded and the workhouse became part of the West Derby Union.

During 1842-43 the workhouse was enlarged, becoming almost self-contained, housing its own bakery, kitchens and stables. It became one of the largest workhouses in England, with an official capacity of 3,000 inmates, but accommodating 5,000 at times. During this period, claims of declining standards within the workhouse were made, with allegations of prostitution and access between certain male and female wards. It was rumoured there were certain areas of the workhouse the governor was afraid to visit at night.

In September 1862 a fire at the workhouse destroyed one of the children’s dormitories, and the church, killing 21 children and two nurses. In 1865 trained nurses began providing care for those in the workhouse and infirmary.

Liverpool philanthropist William Rathbone (1819-1902) funded placements for 12 nurses who had been trained at the Nightingale School in London. Florence Nightingale (1820-1910) recommended nurse Agnes Jones (1832- 1868) to him to act as a Superintendent for this pioneering work, who took on the job. Agnes was supported by 18 probationers and 54 female paupers; each paid a small sum. The successful scheme led to all workhouse infirmaries, throughout the country, being staffed by trained nurses.

The Brownlow Hill Workhouse closed in 1928. The site was put up for sale in 1930 and acquired by the Catholic Church as the site for its new cathedral. The buildings of the workhouse were demolished in 1931.

In 1847, the worst year of The Great Hunger, it is estimated that 296,000 Irish people arrived in Liverpool. They were supported by outdoor relief under the Poor Law and private charities. Indoor relief was supplied in places like the Brownlow Hill Workhouse, despite reluctance among the Irish migrants to enter as there was considerable shame attached to this. Nevertheless, need prevails and many were admitted; eventually the institution was unable to cope with demand. This led to most of those who had already fled The Irish Famine, having to resort to outdoor relief as their main source of support.

In February 1847 the select vestry reported outbreaks of typhus in the Brownlow Hill Workhouse. To avoid having fever wards in the building, parish officials opened temporary fever sheds in Brownlow Hill, adjoining the workhouse. Residents -fearful of contracting typhus- protested the use of the sheds. Typhus became known as the ‘Irish Fever’. During 1847 circa 6,000 Irish people were admitted to the workhouse; by March 1848 29% of the admissions to the Brownlow Hill Workhouse (sometimes known as ‘the Liverpool Workhouse’) were from Ireland, rising to nearly 50% a short while after.

On 16 April 1847 John and Catherine Brannon, and their three children, were admitted to the Brownlow Hill Workhouse – all died. On 13 May 1847 Roger and Catherine Flynn, and their six children, were admitted to the same workhouse, all suffering from typhus. By 28 July, seven members of the family had died. On 20 May 1847, four children from the McIntyre family were admitted. On 4 June Margaret (aged 10) died; on 14 June John (aged 7) died; on 17 June Bridget (aged 19) died and on 6 July Mary (aged 12) died.

The above information was taken from The Great Hunger Commemoration Service, 1997.