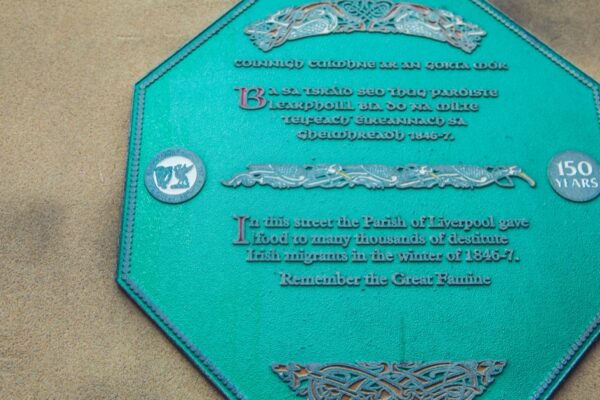

The Fenwick Street Relief Station is marked with a plaque on the corner of Fenwick and Brunswick Streets. Research suggests the closest post code to the plaque is L2 0UU.

The Fenwick Street Relief Station is marked with a plaque on the corner of Fenwick and Brunswick Streets. Research suggests the closest post code to the plaque is L2 0UU.

The exact location of the original relief station is unknown. Fenwick Street and Brunswick Street were widened in 1922 and the old lanes demolished for the reconstruction of the India Buildings. The Liverpool Irish Famine Trail plaque, representing the Poor Law relief station, stands on the Fenwick Street gable end of The Alchemist restaurant on Brunswick Street.

Until 1834, Poor Law in England was administered by the vestry committee of the local parish church, which in Liverpool was based at Our Lady and St Nicholas on the corner of Chapel Street and The Strand. A parish church has stood on the same site since the 13th century, when Liverpool was just a small fishing village. Chapel Street, one of Liverpool’s original streets, runs alongside the church. Water Street, at the end of Fenwick Street, was originally called Bank Street.

The act of 1834 brought an end to parish vestries administering the Poor Law in Britain, but little changed in Liverpool during the period. Even after the Liverpool Select Vestry Act was set up in 1842, and direct control was removed from the parish, the Rector still chaired the Poor Law Board and the church wardens were ex officio members. By 1842, outdoor relief had all but ended and indoor relief in the workhouse was the norm for those who could not find a living independently.

Fenwick Street continued to operate an emergency relief system. This became overstretched in 1846 when Irish immigrants began flocking into Liverpool in their thousands. Some came to stay. Some moved on to other British towns and cities and others shipped-out to America or beyond.

Immigrants disembarking at the Clarence Dock, often in need of immediate relief, would make their way down to the parish offices in Fenwick Street. In January 1847, the number of incidents of relief totalled 370,359. Though not primed to, Liverpool was -in effect- running an Irish Famine relief operation. Adding further complexity to a strained set of circumstances was a language barrier; many of the immigrants were Gaeilge speakers who would not have understood the language of officialdom. Wary of fraudulent claims being made, Mr Austin, the Assistant Poor Law Commissioner, initiated an investigation. He concluded that settled Irish people were borrowing children to present at Fenwick Street to get more food. He issued his findings on 26 January 1847, suggesting that providing relief at Fenwick Street cease.

Instead, Mr Austin proposed claimants should be visited in their homes and -once approved- given a ticket to support their claim at a soup house. Three soup houses -in Flint Street (South End), Pickop Street (Vauxhall) and Gill Street (near Brownlow Hill)- fed the poor. It is thought the select vestry, managed to stave off wide scale starvation.

The challenge the select vestry faced was articulated by their Chairman, Rector Augustus Campbell, in a letter to the Liverpool Mercury, printed on 29 Jan 1847:

“The working classes are becoming exasperated at the […]preferences of

Irish to English poor. The ratepayers are becoming clamorous under a sense of the injustice by which they think they are made to pay such an undue proportion of what they consider at least to be a national burden; …the parish of Liverpool … contained by the last census not quite 224,000 souls … they alone are burdened while the rest of the borough and the adjoining townships and parishes are free … the property of Ireland ought generally to be made to support the paupers of Ireland … but if […] this is […] impossible –if one of the most fertile islands in the world, with a landed rental, as is said, of 12 or 13 millions a year, and which in the last year exported, as is said, 1,300,000 quarters of grain, besides other provisions, valued at several millions sterling, really […] cannot support its own poor[-] then they think that it is a national calamity, which ought to be borne by the whole nation, rateably, and not in an undue proportion by one particular parish…”