As programmers, the Festival often scans the horizon for the best of talent. In March 2021, we were looking for interesting Irish podcasts to help ease us through lockdown and came upon The Irish History Podcast. With over 30,000 followers, we thought we’d better give it a go. Running the show is Fin Dwyer, an Irish historian, author and its creator. He has published two books and is a regular on other podcasts and radio. Over ten years The Irish History Podcast has emerged as one of Ireland’s leading shows. Through a series of diverse topics (from the Norman Invasion, to the Great Famine and his recent work on the Irish War of Independence) he has garnered a global audience. Here, Fin tells us about the formation of the Liverpool’s Irish community during the famine, whilst in his live event (2pm, Sun 24 Oct 2021) he’ll consider the living history of the community, with local guests.

Ireland and Liverpool: A traumatic history

Strange beginnings

In 1311 a merchant -Robert Thursteyn- was brutally murdered in the streets of Dublin. Thursteyn hailed from an old Dublin family and the authorities immediately began the hunt for his killers. It didn’t take long before six sailors were accused of the crime. While the ringleader -Thomas le Whyte- fled the city, his five accomplices were hauled before a Dublin court. Amongst the five was the Liverpool native: Richard Faber. He would become one of the earliest known residents of Liverpool to appear in Irish history, but in the weeks following the murder he would also achieve a strange fame to claim.

Faber, and his fellow sailors, had little chance when tried for the murder in a Dublin court. They were outsiders, accused of killing a well-known resident of the city. It came as little surprise when they were sentenced to death. However, Faber was about to enter the history books, in Dublin, when he and the other condemned men were taken to the gallows and hanged. In a somewhat miraculous turn of events Richard Faber, despite suffering the same fate of his fellow sailors, regained consciousness as he was being buried. He had somehow managed to survive the hanging and eventually successfully escaped Dublin.

Bizarre as his story was, Richard Faber is one of the earliest recorded connections between Liverpool and Ireland. That said, there is little doubt that contact long predated the medieval sailor. Until modern times, the seas were frequently the fastest means of transport and communities -on both sides of the Irish sea- were in constant contact. Our focus, will be the history of the last two centuries, which forged the strong links between Ireland and Liverpool that we know today.

One could argue this is not exclusively down to the size of Liverpool’s Irish community, but also the extremely traumatic and, at times, painful history that forged it in nineteenth century, beginning with the Great Hunger of the 1840s.

The Great Famine

Long before the Great Famine Liverpool had a large, well established Irish community. Rising levels of poverty in Ireland, combined with opportunities in Lancashire, saw large numbers of Irish people move to Merseyside. By 1845, some 50,000 Irish settlers were already calling Liverpool their home.

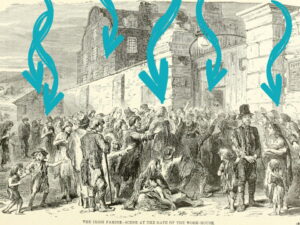

Even so, the nature and identity of this community changed dramatically between 1845 and the early 1850s. During the late 1840s crop failures, combined with racism -and ruthless economic policies pursued by successive British Governments- resulted in the deaths of around one million people during An Gorta Mór (The Great Famine). By late 1846 those who could escape starvation and disease at home sought sanctuary overseas. Emigration on a scale previously unknown in Ireland took hold and within five years over one million had left the island.

The vast majority of these people landed in Liverpool. The sheer numbers arriving in the city at the time is staggering. During the first three months of 1847 alone, 120,000 Irish famine refugees landed in Liverpool. Most would continue their journey onto their ultimate destination – the United States. Nevertheless, a considerable number remained in Liverpool. These tended to be the poorest who could not afford the relatively expensive transatlantic passage.

Life in Liverpool

The famine migrants in Liverpool had to endure immense hardships as they forged their new home on Merseyside. Most arrived severely weakened, with little or no money. Disease was also rampant among these people fleeing famine. The Liverpool Mercury, on 12 April 1847, reported on soaring disease in the city, stating Liverpool was becoming a ‘Skibbereen on a large scale’. This referenced the Cork town where famine conditions had been appalling. This situation put immense pressure on the city authorities. In 1845 they had been providing poor relief to 900 people. Within twelve months 13,000 people were dependent on this aid.

While there was some initial sympathy to the plight of the Irish among many Liverpool natives this changed from 1846 onwards. They resented having to pay for poor relief for famine emigrants, while sectarianism fostered suspicion towards the largely Catholic Irish.

Increasingly legal technicalities were used to deny relief to the impoverished Irish. While the authorities hoped this would force them to leave the city, the desperate famine exiles had nowhere to go. Instead, this treatment only served to create deep and long-lasting resentments among the Irish community in Liverpool.

1850s life

While the famine would ease in the early 1850s, life remained extremely difficult. Research by historians Catherine Cox, Hilary Marland and Sarah York has revealed the reality of life for many in the Irish community in the later nineteenth century.

By 1849 Irish people accounted for 40% of the population in some Liverpool Jails. By the late 1850s, Irish people made up around 50% of those incarcerated in the Rainhill Asylum on Merseyside. It’s difficult to state precisely why this was the case. It’s very possible that Irish people committed more crimes because they were poor and suffered from mental health issues linked their experiences during the Famine. Additionally, there is little doubt racism also played a significant role as well. Stereotypes meant that those in authority were more likely to believe Irish people were guilty of crimes, while the notion that they were more temperamental resulted in larger numbers being sent to asylums.

The history of Liverpool’s Irish community in the nineteenth century was undoubtedly painful. Resentments at being forced to leave Ireland, racism and sectarianism all made life more difficult. Nevertheless, it was in this cauldron of hardship -accompanied by a desperate will to survive- that the modern connection between Liverpool and Ireland was forged. Through the twentieth century this has changed and developed, but this intense chapter in our history helps to understand the continued affinity shared between Ireland and Liverpool.