‘The ‘pool feels itself closer to Dublin, New York, even Buenos Aires, than it does to London… it’s very aware of its own myth and eager to project it’, George Melly, jazz musician and artist, Revolt into Style, 1970

‘There is a great love and unity in this city, there’s a great feeling of togetherness which materializes in the Kop, where one thought spreads among the crowd … it’s not just going there to watch a football match it’s really a form of worship of a great city by the people’, Arthur Dooley, sculptor, 1972

The Liverpool Irish Festival celebrates the connections between Liverpool and Ireland through, walks, talks, theatre, film, music and art. In so doing, it acknowledges that the one of the dominant strands in the formation of the city was Irish immigration. The Office of National Statistics estimates that 50 per cent of the population of Liverpool has Irish heritage; whilst the Liverpool Echo puts the figure higher, at 75%. This ‘Irishness’ of Liverpool is often cited in accounts that try to explain Liverpool’s distinctiveness amongst English cities.

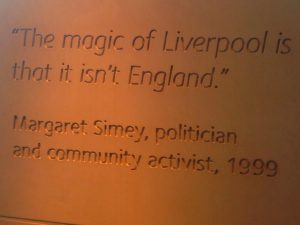

In fact, partly as a consequence, the ‘Englishness’ of Liverpool is frequently questioned. ‘Is Liverpool English?’ was Andrew Marr’s query recently on Radio 4’s Start the Week (broadcast on 26 Sept 2016 available on BBC Radio iPlayer). In the Museum of Liverpool there is an inscription on a pillar of a quote from Margaret Simey: ‘The magic of Liverpool is that it isn’t England.’

The strong identity of the city, which centrally involves – in the words of local blogger Ronnie Hughes – ‘a sense of place’, is the product of many influences, historical events and representations of the city (internal and external). It is this identity that has underpinned the support for the Hillsborough families for three decades. Additionally, this ‘sense of place’ underpins support for both football teams; it underpins the political distinctiveness of Liverpool and it underpins the warm reception being from Liverpool can evoke all round the world.

In this strong identity of place, how is it possible to disinter the exact contribution of the Irish, Welsh, Manx, Chinese, Somalian or Caribbean immigrants to Liverpool? Each has been notable and often it may have been the friction or conflicts between different groups that was much more significant in producing the city, than the notion that Liverpool has been one big ‘melting pot’.

I say this because Liverpool in the nineteenth century was a time of extensive immigration from Ireland. Importantly, this was also a time when Liverpool was the gateway for global emigration from all over Britain and Ireland, and for many other northern Europeans. Thus, it could be argued Liverpool bears comparison with New York more than any other English city. In both instances the throughput of the port was definitive for the local economy and for their perception as cosmopolitan places, both facing outward across the Atlantic.

In many ways the Irish roots of the Liverpool population are masked by an alternative identity: ‘being a Scouser’. Liverpudlianism is based on the perception of the city as unique. This identity is essentially a working class one, emerging from the history of a city made of various economic and political struggles and the experiences of a number of immigrant groups, of whom Irish Catholics were the largest.

The young people I interviewed in Liverpool when researching Irish identities in Britain (all of Irish descent) constantly itemised what was good about the city or gave an explanation of why Liverpool was better than its image. All of their comments revealed that pride in being from Liverpool is based on a conviction that the city is different from everywhere else. The roots of Liverpool exceptionalism lie within the city as well as amongst its detractors, elsewhere in (southern) England.

One basis of Liverpool’s exceptionalism has been the very high proportion of the population who are Roman Catholics compared with anywhere else in England, largely the result of immigration from Ireland. In Britain the only real comparator is Glasgow. However, even today, the proportion of Catholics (nominal or otherwise) forming the population of the Archdiocese of Liverpool – 46% – dwarfs that of the Archiocese of Glasgow (28%).

This religious heritage and the sectarianism that used to characterise the city (Liverpool was called ‘the Belfast of England’ in 1909) is another important aspect in both the oft-cited uniqueness of the place. It may help to explain why a strong local identity was a requisite of modernity for Liverpool. This identity needed to be one that people of different ethnic and national origins, religious backgrounds and ultimately different class origins could all subscribe to because – given local economic and political conditions – these social and cultural differences had sometimes produced violent conflicts.

When researching Irish identities in Britain, I found that for third generation Irish (i.e., those with grandparents born in Ireland) and certainly from the fourth generation onwards, the likelihood of the individual subscribing to a British or English identity was high. Liverpool was the main exception to this, a place where the local identity trumped the national options (English, British or Irish) for three-quarters of the young people who participated in the research (all of whom were third- to fifth-generation Irish).

In the USA, whatever degree of allegiance people have to their Irish origins they can opt to tick ‘Irish American’ on the Census form every ten years and ticking that box must mean many different things. In the very different political culture of the peculiar multi-national state that is the United Kingdom ethno-national differences have always carried more threat and considerable effort has been expended trying to contain them.

The Liverpool Irish Festival got underway in 2003 so now is in its fourteenth year. Ever since The Good Friday Agreement was signed in 1998 one of its consequences has been an easing of the inhibition many people of Irish origins in England felt in celebrating their heritage in public spaces. In Liverpool those Irish origins are tied up not only in connections with Ireland but in the very fabric of the city and its identity – all of which is being celebrated from 13-23 October 2016.

Prof. Mary Hickman is Emeritus Professor of Irish Studies and Sociology, at the Irish Studies Centre, Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities at London Metropolitan University. A sociologist, focusing on migration, diaspora, ethnicity and race, Mary’s latest book is Women and Irish Diaspora Identities (2014). Mary is a Trustee of the Liverpool Irish Festival and the London Irish Centre as well as Chair of Votes for Irish Citizens Abroad.

Twitter: @MaryJHickman

Further reading (and watching!)

In My Liverpool Home was a poem by Pete McGovern. You can read the poem using this link. It has been sung as a song by many and can be viewed as performed by The Spinners, below.