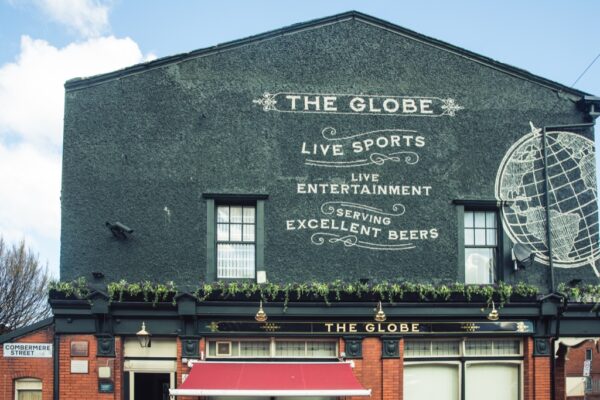

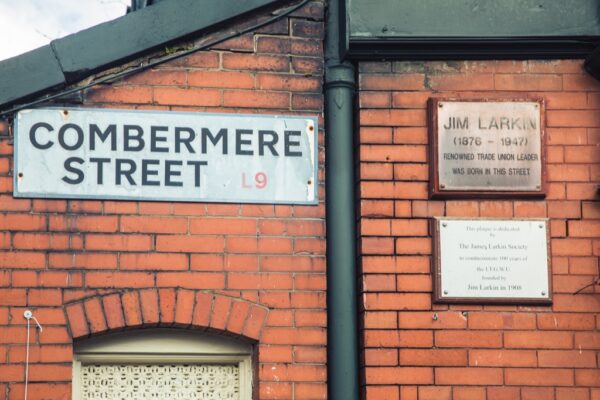

In the 1990s this site was marked as a plaque site, because a plaque marks the site of James Larkin’s birth. However, as this is not one of the suited Irish Famine plaques, so we are no longer labelling it as a ‘plaque site’. To locate the birth marker, you will need to walk in to the pub car park on Combermere Street and look up at the building’s side, which faces up Park Road and away from the city centre. As you will see in the images, the plaque is quite high up and on the side of The Globe, a pub, which is slightly problematic as Larkin was teetotal.

In the 1990s this site was marked as a plaque site, because a plaque marks the site of James Larkin’s birth. However, as this is not one of the suited Irish Famine plaques, so we are no longer labelling it as a ‘plaque site’. To locate the birth marker, you will need to walk in to the pub car park on Combermere Street and look up at the building’s side, which faces up Park Road and away from the city centre. As you will see in the images, the plaque is quite high up and on the side of The Globe, a pub, which is slightly problematic as Larkin was teetotal.

James ‘Jim’ Larkin -the son of Irish parents James Larkin and Mary Ann McNulty, both

from County Armagh- was born in Liverpool, 21January 1876. His sister, Delia, was born just two years later. Aged five, he was sent to live with his grandparents in Newry, Ireland. James returned to England in 1885, finding employment as a dock labourer. He was a quick convert to socialism and joined the Independent Labour Party in 1893, spending his spare time selling The Clarion.

In 1893 James became a foreman dock-porter for T & J Harrison Ltd. The following year he was sacked for striking with his men. Work for James moved between Liverpool and Ireland during this time, with other trips taking him further afield. Despite this, James remained active in the unions and in 1906 he was elected General Organiser of the National Union of Dock Labourers (NUDL).

Having learned the ropes, James established his own union, the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU). As well as Dublin, this union had branches in Belfast, Derry and Drogheda. By 1908 the ITGWU was running a political programme advocating a “legal eight hours’ day, provision of work for all unemployed, and pensions for all workers at 60-years of age. Compulsory Arbitration Courts, adult suffrage, nationalisation of canals, railways, and all the means of transport. The land of Ireland for the people of Ireland”.

Leaders went on to include notable figures such as James Connolly (1868-1916); whilst supportive activists Countess Markievicz (née Gore-Booth;1868-1927) and Patrick Pearse (Pádraig Anraí Mac Piarais; 1879-1916) called for worker’s rights alongside the ITGWU.

Based on success with some smaller industrial disputes, involving sympathetic strikes

and boycotting goods, ITGWU and Larkin’s attentions moved to the unskilled workers of Guinness and the Dublin United Tramway Company. The craft workers already had unions, but unskilled labour did not. Neither company wanted external unions influencing matters, but the two companies held different approaches towards their recruits. William Murphy, Chair of Dublin United Tramway Company, in fear of unionisation dismissed forty workers he suspected were colluding with the ITGWU. He followed this, with a further 300. This action forced the tram workers to strike from 26 Aug 1913. In response, 400 Dublin employers demanded workers pledge not to join the ITGWU or sympathetically strike, all spearheaded by Murphy’s actions. Retaliating against the strikers, employers locked-out workers that refused the pledge; backfilling labour with workers from outside Dublin. By September, 20,000 workers were locked-out. Though Guinness refused to lock-out its workers, it dismissed 15 sympathy strikers. Collectively, the lock-outs left the unskilled labour at the mercy of donations for the British Trade Union Congress and the ITGWU, which were woefully under- resourced and inadequate for the scale of need.

What followed were sedition and incitement to violence charges and arrests; the disguised harbouring of union leaders; public speeches; police raids and baton charges and the formation of the Industrial Peace Committee, which the employers refused counsel with.

After the violence of the police-raids, James, teamed with Jack White (1879-1946) and James Connolly formed the Irish Citizen Army, training the unskilled and unemployed to defend themselves in the event of police brutality.

Throughout the seven-month lock-out, James’s name -and those of his peers- was pilloried through the press, much of which was owned by Murphy. Name-and-shame lists were printed of those breaking strike action or resorting to sending family away from the city in bids to keep themselves nourished. Calls from the ITGWU for strike action in Britain fell on deaf ears and eventually the unskilled workers, who had withheld their labour until the brink of starvation, were forced back to work on 18 January 1914 with many signing pledges against ITGWU membership.

On the surface, the 1913 Dublin lock-out was a failure, eroding the ITGWU, but it set the course for union reform, worker rights, public spending and much else. It fuelled political concerns about the relationship with Britain and Home Rule; creating questions around establishment actions, the use of violence and the need for civil, armed protection.

Through James wasn’t born at the time of the Irish Famine, the living conditions for Irish migrants -and the communities they built- shaped James’s childhood and the world in which he lived. The cultural loss, broken families and long-term effects of such devastation must have been ever present in the working communities, social life and faith of those James was surrounded by, in Liverpool and in Ireland. His early working life will have been shaped by the workers and families that came to Liverpool from Ireland in the 30-years before. In Ireland he will have seen the gaps left by those who fled or perished and the meagre conditions for those that remained. James’s commitment to improving the life of workers and the working-classes, in Liverpool and in Ireland, had considerable influence on the trade union movement on both sides of the Irish Sea. The repercussions of this time are still felt in the Trade Union world, globally. Though questions about citizen armies may cloud arguments, James’s original position of pacifism continues to be regarded as a mark of the man.

James Larkin Way (L4 1YQ) in Kirkdale, Liverpool, is just off Scotland Road, linking Lambeth Road and Leison Street, close to The Rotunda. Additionally, a coastal road -James Larkin Road- in north Dublin, Raheny, leads between Mount Prospect Avenue (near Dollymount), through to Howth Road, Kilbarrack. A famous quote from James, stated at the 1913 Dublin Lockout, runs “A fair day’s work for a fair day’s pay”.

To celebrate Liverpool’s year as European Capital of Culture, the Liverpool Irish Festival held a James Larkin Evening at The Casa, the dockers’ pub on Hope Street, Liverpool. This was attended by Francis Devine who wrote the general history of the trade union movement in Dublin and the formation of Services Industrial Professional and Technical (SIPTU). It was introduced by Liverpool Irishman Marcus Maher, who travelled from Dublin to present a specially commissioned painting by Finbar Coyle, to James Larkin’s last remaining Liverpool nephew, Tom Larkin. The painting reflects on one side Dublin and on the other side the Liver Bird and his home city of Liverpool.

The Transport and General Workers’ Union General Secretary and activist Jack Jones (1913- 2009), whose full name was James Larkin Jones, was named in honour of his fellow Liverpudlian.

Members of the James Larkin Society have been fundraising to erect a statue of Larkin in Liverpool in his memory. James is immortalised in a Oisín Kelly statue, installed in O’Connell Street in Dublin in 1979, commemorating an iconic photograph taken of him addressing a Dublin crowd in 1923. There, ‘Big Jim’ stands on a plinth. The inscription on the front of the monument is an extract in French, Gaeilge and English from one of his famous speeches:

-Les grands ne sont grands que parce que nous sommes à genoux: Levons-nous.

-Ní uasal aon uasal ach sinne bheith íseal: Éirímis.

-The great appear great because we are on our knees: Let us rise.

“A mutual arrangement, I repeat, is the only satisfactory medium whereby the present system can be carried on with any degree of satisfaction, and in such an arrangement the employers have more to gain than the workers” – James Larkin