Every year, Liverpool Irish Festival partners with Bluecoat Display Centre to select an Irish maker, whose work we exhibit in October. This year, Níamh Grimes’s delicately made jewellery was selected for its links to Irish superstition and the protection it provides the wearer.

Considering how personal everyday rituals build towards seasonal, anniversary or celebratory events, Níamh’s work connects with our theme of anniversary, on a deep, year-round level. The protection her work provides develops care, connection with seasons and with one another. Below, Níamh unravels her metallic philosophical thread for us, so we can see inside the making, mystery and magic.

(For reference, there’s a short glossary further down the page).

Article contents

I’m an artist jeweller living and working in Manchester. I specialise in metal casting (predominantly investment casting). I use these processes in conjunction with others to create wearable objects, which are deeply imbued with historical and ritual narratives. Additionally, I use inherited and found objects to preserve and reimagine stories and customs of the past.

Recently, my work has been inspired by traditional superstitious Irish folk customs -especially those surrounding ‘The Otherworld’- producing contemporary, ritual objects. These wearable pieces connect me with my ancestors by re-imagining the protective practices they used over generations. They also encourage the wearer to create mindful, personal everyday rituals. Doing so helps us to connect with seasonality and to welcome small forms of celebration.

Weaving traditional and contemporary practices

Weaving the folk wisdom and practices of our ancestors into our contemporary lives deepens our understanding of cultural heritage. Simultaneously, this nurtures our sense of identity and belonging. Understanding ancient customs through their crafts gives us the opportunity to relate intimately to bygone days. Looking at the folklore; folk music and art; dialects and beliefs in small communities creates connection between times. These stories and crafts are tools for archiving history. They familiarise us with the people and landscapes from which we came. Such pursuits embody the driving force of my research and practice.

Context

The body of work presented during In The Window focusses on past Irish folk customs. Especially those surrounding people’s belief in ‘The Otherworld’; a mostly invisible realm existing parallel to our own. The Otherworld was home to fairies like the Bean Sidhe (banshee), the púca and other unearthly beings. These creatures were thought to make their way into our mortal world. Here, they’d offer domestic help, play tricks, forbode death and -sometimes- even kidnap humans.

My Irish background is a constant source of inspiration. I want to unearth how it might have felt to live in a time when everyday rituals were intertwined with the appeasement of the ‘Good Folk’. Therefore, my works relate to some of the objects connected to these customs. This includes handmade lace, quenched coal, iron, salt crystals and vials of anointed oil. Pieces explore how such objects harbour tactile and collective memory and how their stories might change when they become adornments for the body.

Using found objects to imbue meaning

Each found object -or material I’ve incorporated- tells a story of protective ritual. The small pieces of quenched coal recall an old rural Irish custom. People would take a coal from the hearth of a friend or family member, quenching it in a bucket of water, and keeping it in a pocket to ensure safety on their walk home. Similarly, iron -in the form of nails and horseshoes- were positioned over beds and doorways to ward off otherworldly threats. Salt was sometimes sprinkled at domestic thresholds and stitched into corners of children’s clothing for protection.

The casts and forms within this collection are inspired by traditional Irish lace. They behave as a web, connecting references to Irish folk history, material culture and spiritual beliefs. Irish lacemaking is believed to have been popularised by the wealthiest members of society, whose own pieces were imported from Venice in the Middle Ages. These inspired designs which -later- became known as ‘traditionally Irish’. Despite its aristocratic origins, lacemaking became a common craft. It was often practiced by young girls hoping to financially support their families.

Questions arising

The idea of circles of women, meticulously working on lace cuffs and trims made me consider: what environment did lacemaking provide for these craftspeople? Did it behave as a conduit for discussing personal and local matters? If so, how many conversations were populated by musings on local folklore? About beliefs surrounding The Otherworld or sharing rituals one might use to ensure good fortune? And -most importantly- how did these tales, beliefs and practices tie people to the landscapes they called home?

Poetry

Níamh Grimes, ‘The Underbay’

‘The Underbay’ (poem below) was written in response to a visit I took to Galway Bay. The meeting of the water and earth, at this place, appeared to me as a threshold. In a literal sense it was a changing of landscapes, from solid ground to sea. Beyond this however, I couldn’t help feeling how the bay might inspire beliefs and stories of it being a gateway between our world and The Otherworld.

When the grey, frothing tongues of saltwater lick my ankles above hiding weever fish, In places where hands and feet long to become hooves and tails,

The ring of braided rowan tracing my eye,

The gorse oil still evident from its fruit-scent on my fingers, The coal dust lining my pocket,

Hold me to this stone you sheltered inside, by the dancing of your hearth.

Two work examples

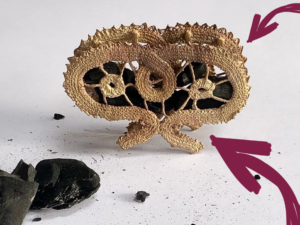

Lace caged coal brooch

1 ‘Lace Caged Coal Brooch’ takes inspiration from the ritualistic use of quenched coal (mentioned above). The front and back faces began as pieces of antique Irish lace. I cast these forms into brass, connecting them with bars to create a cage-like structure.

1 ‘Lace Caged Coal Brooch’ takes inspiration from the ritualistic use of quenched coal (mentioned above). The front and back faces began as pieces of antique Irish lace. I cast these forms into brass, connecting them with bars to create a cage-like structure.

To use the Lace-Caged Coal Brooch, the wearer takes a piece of coal and places it inside the brooch. It must slide through the widest gap at the top. The wearer passes the brooch through a flame and must then quench the brooch (and coal) in cold water, before attaching it to their clothing. The coal sheds blackened particles onto the fabric beneath, bestowing a layer of its protective essence to the wearer. They are now able to endure their journey, reassured that no otherworldly harm should come their way.

Crystalised salt tiered lace necklace

2 ‘Crystalised Salt Tiered Lace Necklace’ combines brass casts (made from genuine antique Irish lace) with salt crystals, which I have grown onto the surface of the metal. The salt crystals are sealed with lacquer to help their structural integrity.

2 ‘Crystalised Salt Tiered Lace Necklace’ combines brass casts (made from genuine antique Irish lace) with salt crystals, which I have grown onto the surface of the metal. The salt crystals are sealed with lacquer to help their structural integrity.

I designed the chain to mimic the patterns within the brass lace panels. Hovering between the lengths of chain are what I call ‘lace coins’. These are thin sheets of brass, on which I’ve embossed pieces of Irish lace. From the sheet, I saw small shapes according to the embossed pattern. I think of them as ‘coins’ in the hope they evoke having a talismanic keepsake for comfort. It is a ritual jewellery piece.

‘Crystalised Salt Tiered Lace Necklace’ is one of my most personal. I made it with the intention of wearing it during tumultuous periods to provide a few quiet moments of reflection. The cast lace evokes folk memories for me. It reminds me of the custom of lacemaking in Ireland. It imbues the necklace with the ability to connect me to my ancestors and nurture a sense of belonging. Combined with salt crystals -believed to be protective against otherworldly beings- this piece forms a shield to keep me grounded, connected and safe.

Excavation, renewal and futures

My practice is a constant excavation process. Through it, I inspect personal narratives relating to my heritage; the folk beliefs I grew up around and their ancient roots. Tactility and materiality are intrinsic to my work. I often use these characteristics to try to trigger blood memory and to charge the works with talismanic properties.

Metal casting, to me, feels like an alchemical method of preserving that which is eroding with time. It reimagines these stories. The original object is destroyed, leaving behind an ‘immortal’ version made from metal. When I combine my casts, with found or inherited materials, I must consider how each item alters the other’s history to create a new reality.

I hope this reaction inspires others with an eagerness to reconnect with the magical thinking held by their ancestors. This is what tied them to their homelands, offering a sense of identity and belonging. On a personal level, my work reinforces an eternal tie between myself and the landscapes, beliefs, rituals and now absent people who came before me.

Glossary

- Bean Sidhe or Banshee – a fairy whose keening (sorrow-filled singing) is thought to foretell death, usually in the family

- Blood memory – our ancestral/genetic connection to our native language(s), songs, spirituality, and teachings. Blood memory may be observed as the feelings of comfort and familiarity experienced when we’re near to these things

- Casting – a process in which liquid metal is poured in to a mould. Once cold and solid, the metal cast is removed revealing a 3D shape. There are various types of casting involving different mould materials for different molten metals

- Collective memory – Collective memory refers to the shared pool of memories, knowledge and information of a social group that is significantly associated with the group’s identity

- Folk customs – Behaviours and beliefs associated as traditional to a group. Typically encompasses the likes of storytelling, spiritual beliefs, celebrations and material culture, including traditional crafts native to the group

- Good Folk – Also referred to as ‘fairies’ in Irish folklore and tradition. The spirit beings who inhabit the Celtic Otherworld and sometimes pass through or pay visits to people living in our mortal world. The term ‘The Good Folk’ is deemed more respectful than ‘Fairies’, which people in some localities believed would anger the beings

- Otherworld, The – The realm in Celtic mythology where deities and/or the dead live

- Púca – naughty creatures that can change shape and like to create mayhem

- Tactile memory – The memories and associations we have in response to tactile stimuli and the feeling of touching certain objects.

Artistic statement and theme

Each year the Liverpool Irish Festival sets a programme theme. Past themes have included hunger, exchange, unique stories; creatively told, migration, the meaning of ‘Irishness’ and conviviality. To build the theme, we pose questions to help us interrogate and understand Irishness, its influence and its creative spirit. 2023’s theme is ‘Anniversary’ – read more here.

In the Window partnership

Bluecoat Display Centre is an independent, regional centre for artistic activity. It brings together craft makers and audiences, in an environment that encourages creativity, collaboration and the exchange of ideas. The Bluecoat Display Centre runs a gallery, as well as education and community outreach programmes. It’s been a registered charity since 2010, based in Liverpool. The Centre provides a retail platform for 60+ local and 300+ nationally selected contemporary craft makers and designers. Established as one of England’s earliest craft and design galleries (1959), Bluecoat Display Centre was the first public gallery space within The Bluecoat. It’s an advocate, facilitator and audience maker for contemporary crafts.

Liverpool Irish Festival brings Liverpool and Ireland closer together using arts and culture. It is this use of arts and culture as an instrument for observing, learning, sharing and debating Irishness, in the particular context of Liverpool, which makes us unique. We represent Northern Ireland, the Republic and the Irish diaspora’s creativity throughout the Festival. Our thematic approach to programming, critical-thought and curation develops depth, resonance and inclusion. In this context, we believe the Liverpool Irish Festival is the only Irish arts and culture led festival in the world; we can’t find another!

Bluecoat Display Centre and Liverpool Irish Festival have partnered on In The Window events for October for many years. Together, they have presented work from Laura Matikaite, Mike Byrne, Sophie Longwill, Rory Shearer, Christy Keeney, Berina Kelly and Catherine Keenan, among others.

Associated events (please note, these may have passed)

Related writing