Article contents

- 125 years of art, culture and progress

- In defence of kindness

- Respect in disrespectable circumstances

- Authority injustices

- Cross-societal harm

- Against Christian morality

- The death penalty harms us all

- Contemporary relevance

- Writer biography

- Back to the top

125 years of art, culture and progress

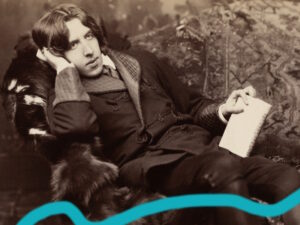

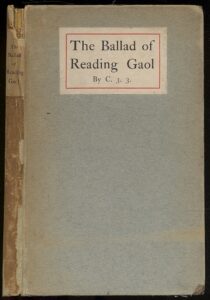

2023 marks the 125th anniversary of the publication of Oscar Wilde’s famous poem, The Ballad of Reading Gaol. The full poem is available to read here. He began writing this shortly after his release from prison, where he’d been incarcerated for the crime of loving other men. This was termed as ‘gross indecency’ under the 1885 Labouchere Amendment to The Criminal Law Act. Imprisoned for two years (May 1895-May 1897), Wilde was held in a number of English prisons, including HMP Reading. While incarcerated he witnessed terrible acts of official cruelty. Additionally, he beheld tremendous acts of kindness, enacted by prisoners and even their captors.

2023 marks the 125th anniversary of the publication of Oscar Wilde’s famous poem, The Ballad of Reading Gaol. The full poem is available to read here. He began writing this shortly after his release from prison, where he’d been incarcerated for the crime of loving other men. This was termed as ‘gross indecency’ under the 1885 Labouchere Amendment to The Criminal Law Act. Imprisoned for two years (May 1895-May 1897), Wilde was held in a number of English prisons, including HMP Reading. While incarcerated he witnessed terrible acts of official cruelty. Additionally, he beheld tremendous acts of kindness, enacted by prisoners and even their captors.

In defence of kindness

This is notable in Wilde’s letter of defence for Thomas Martin, a dismissed Reading Gaol warder. Mr. Martin was summarily sacked from his role for giving biscuits to a frightened, hungry child prisoner. Wilde pointed out Mr. Martin’s offence was to have fed the smallest boy he’d seen in two years of incarceration. He argued that the weaponisation of hunger in prisons was made possible by the doctrinal assumption that ‘because a thing is the rule it is right’. He condemned the Prison Board for its role as ‘the primary source’ of this cruelty and stated that its only outcome was simple terror.[i]

Respect in disrespectable circumstances

Martin’s intervention -and Wilde’s defense- are examples of the kind of decency and kindness that existed within the violent structures of the Victorian prison system. For Wilde, the greatest example of collective and humane action occurred during his stay in Reading Gaol. There, he beheld the reaction of prisoners to the execution of a soldier, Charles Thomas Wooldridge. Mr. Wooldridge was hanged on 7 July 1896 for murdering his wife the year before. Wilde was struck by his fellow prisoners’ capacity for grace, on the eve of the execution. He recalled how they prayed for Wooldridge as he was about to face the gallows.

The warders with their shoes of felt

Crept by each padlocked door,

And peeped and saw, with eyes of awe,

Gray figures on the floor,

And wondered why men knelt to pray

Who never prayed before.

Authority injustices

For Wilde, the real injustice of the death penalty lay in the state’s refusal to consider the humanity of inmates, particularly condemned men like Wooldridge. Seeing prisoners bent in prayer, on his wing of Reading Gaol, revealed to Wilde the human worth of society’s outcasts. This silent act held up a mirror to the inflexibility of the carceral (prison) state, which matched the violence it sought to punish using its ultimate sanction: the death penalty. Any application of the hangman’s noose, or ‘rope of shame’, was the ultimate act of state power:

For Man’s grim Justice goes its way,

And will not swerve aside:

It slays the weak, it slays the strong,

It has a deadly stride:

With iron heel it slays the strong,

The monstrous parricide*! (ll.361-6)

*Parricide – the killing of a parent of close relative.

Cross-societal harm

Wilde regarded the indiscriminate violence of authority to be universally harmful, inflexible and irrational. Its lethal momentum, or ‘deadly stride’, conveys its immoveable and unreasonable dynamic. This violent energy is met with the poet’s reflection on the state’s denial of freedom to prisoners. In his experience, liberation could be imagined by the inmates as akin to the free mobility of clouds, drifting above the prison yard…

I never saw sad men who looked

With such a wistful eye

Upon that little tent of blue

We prisoners called the sky,

And at every careless cloud that passed

In happy freedom by.

Against Christian morality

For Wilde even the most despairing had rights. This was true to him of Wooldridge because he ‘was one of those/Whom Christ came down to save’. As the state performed its terrible duty, Wooldridge’s death was lamented by the most marginalised and dispossessed in Victorian society; his fellow prisoners. ‘His mourners will be outcast men/And outcasts always mourn’… Wilde continues by condemning the inhumanity of the penal system

This too I know – and wise it were

If each could know the same –

That every prison that men build

Is built with bricks of shame,

And bound with bars lest Christ should see

How men their brothers maim.

With bars they blur the gracious moon,

And blind the goodly sun:

And they do well to hide their Hell,

For in it things are done

That Son of God nor son of Man

Ever should look upon. (ll. 547-58)

The death penalty harms us all

For here, the poem shifts from a reflection on the death sentence to a broader condemnation of imprisonment. Here, Wilde reveals his most progressive proposal: when the state carries out violence against prisoners it has abandoned any claim to moral authority. This includes the death penalty or the act of incarceration itself. These punishments are in and of themselves flawed. In Wilde’s view, these acts degraded everyone who came into contact with the prison system. Whether exercised directly or indirectly, these applications of state power cultivated aggression, betrayal, and hypocrisy. He felt this to be true outside the prison’s walls, within them and as a dehumanising phenomena that affected society as a whole.

Contemporary relevance

The poem remains strikingly relevant today. Dire prison conditions in Ireland, Britain and many other countries are known to continue to harm the mental and physical health of inmates and their loved ones. Despite its perceived modernity, our most advanced capitalist nation -the USA- is also the world’s most carceral state. There, children are still held in prisons, sometimes alongside adults. Over half of the USA’s states reserve the death penalty, for people like Charles Thomas Wooldridge, who have been convicted of murder.

The Ballad of Reading Gaol is best understood within the context of Wilde’s broader, progressive beliefs, rather than a silo of an individual and singular experience. He confronted homophobia in his novel The Picture of Dorian Gray, exposed poverty in his short stories, criticised capitalism in his essay The Soul of Man Under Socialism, and advocated women’s rights in his plays. In many public lectures he called for the recognition of workers’ rights, and demanded that the dignity of labour should be recognised.

In this poem, we find Wilde’s compassionate reflections on the treatment of prisoners, who were among Victorian society’s most marginalised figures. Today, prisoners remain under regimes within which the kind of institutional violence, described by Wilde, continues to punish rather than reform. In Wilde’s time, as today, the struggle against injustice involved a broad approach, and just as Wilde did not fail to address violence against prisoners, children, and women in isolation, we should not either.

Writer biography

Dr Deaglán Ó Donghaile, Research Institute for Literature and Cultural History, Liverpool John Moores University (link). Dr Ó Donghaile is the son of a political ex-prisoner. He is Reader in Late Victorian Literature and Culture at Liverpool John Moores University and author of Oscar Wilde and the Radical Politics of the Fin de Siècle (Edinburgh University Press). He is currently writing a political biography of Wilde.

Dr Deaglán Ó Donghaile, Research Institute for Literature and Cultural History, Liverpool John Moores University (link). Dr Ó Donghaile is the son of a political ex-prisoner. He is Reader in Late Victorian Literature and Culture at Liverpool John Moores University and author of Oscar Wilde and the Radical Politics of the Fin de Siècle (Edinburgh University Press). He is currently writing a political biography of Wilde.

[i] Wilde, to the Editor of the Daily Chronicle, 27th May, 1897, Complete Letters, pp.847-855, p.848

See Deaglán’s talk: