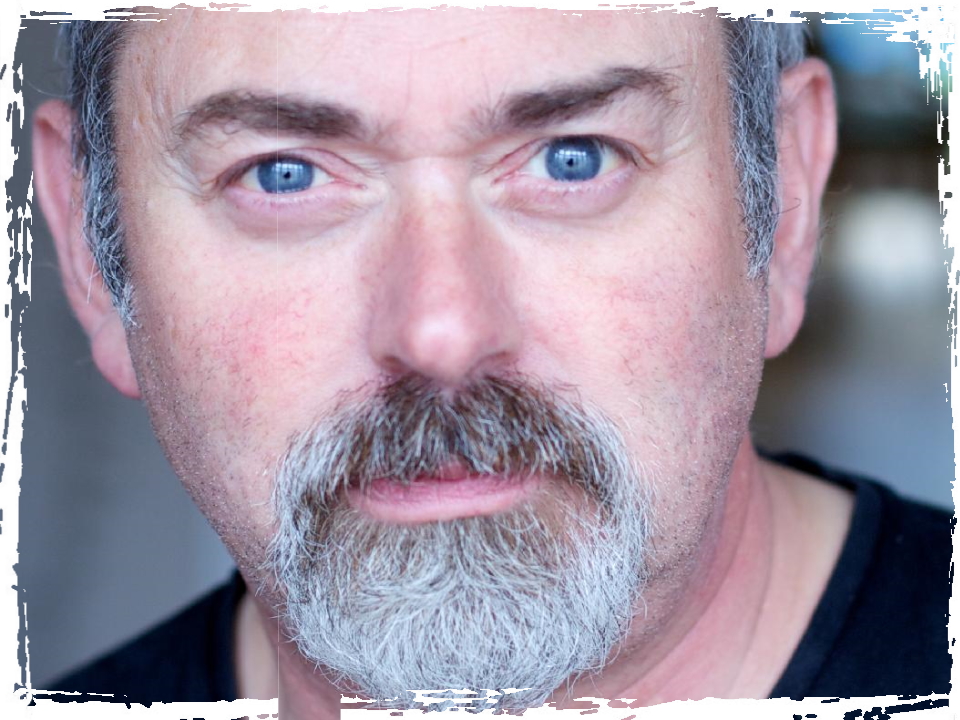

A tribute to Festival Board member Tony Birtill, from friend and colleague Tom Ryan, following his passing on 21 Oct 2021.

A tribute to Festival Board member Tony Birtill, from friend and colleague Tom Ryan, following his passing on 21 Oct 2021.

Aknowledging the speakers and artists we have worked with directly in 2021 and thanking the many more that have contributed.

The Pride of Sefton is a widebeam canal boat owned by The Sovini Group and used by community and charity groups and run by volunteers.

The Mersey Mash is a collection of Festival based interviews, a live screening and online film documenting Liverpool's Irish lives.

After two years of preparation, the Festival was -in June 2021- awarded National Lottery Heritage Funds to start reviving the city’s historic Irish Famine Trail.

From Ireland, to Liverpool -and across the world- exchange celebrates that which brings us closer or drives us apart; to consider identity, heritage and play.

Liverpool Irish Festival seek a History Research Group Lead to head up an exciting project to revitalise the Liverpool Irish Famine Trail.

Liverpool Irish Festival is awarded National Lottery Heritage Funding to revive Liverpool’s historic Irish Famine Trail.

In Liverpool, many of us are aware of the forced repatriation of hundreds of Chinese seaman in the 1940s.

We have stumbled over community stories of families left behind. We have shaken our heads at the inconcievable and overt injustice of a governmental act that denied people their fathers, husbands and friends and we have empathised over the loss. These passive acts are by-products of a lack of evidence and an inability to comprehend the impact. It is a mystery that seems entirely unbelievable and yet men that were there suddenly weren’t; creating ramications that have carried on for seven decades.

In 1945-6, hundreds of Chinese seamen were ’rounded-up’ and deported; sometimes back to China, Singapore or other locations. Official evidence has been hard to come by; with documents strewn across the world and often deliberately hidden from view, making the story difficult to confirm.

Around that time, many of Liverpool’s Chinese seamen met and married English and Irish women; leading to Anglo-Chinese and Chinese-Irish communities; a legacy that continues today.

What of those left behind? Of the men severed from their families and homes? Where did they end up and how did it affect the communities involved? Dan Hancox has written an indepth piece on this very subject: The secret deportations: how Britain betrayed the Chinese men who served the country in the war available in The Guardian (published 25 May 2021; it is also worth noting that there is a follow up article comprising of reader’s comments and thoughts, here).

At 2.30pm, on Thursday 3 June 2021 -marking the 75th anniversary of the deportations- Kim Johnson MP will visit Liverpool Pagoda Chinese Community Centre to meet the children of the forcibly repatriated Chinese seafarers. The intention is to raise awareness and to reissue the request that HM Government formally recognises what Kim Johnson calls “one of the most nakedly racist incidents ever, taken by the British government”.

You can read more about this in press releases, presented in English and Chinese/中文 (click links).

The Liverpool Pagoda Chinese Community Centre welcome the media to attend, to interview those who are willing to be recorded. The event will be live-streamed on Zoom in the hope of including half-siblings in Singapore -and others- affected by the forced deportations.

MP Kim Johnson, Zi Lan Liao (Pagoda Centre Director) and the Pagoda Centre team invite all ‘left-behind-children’ to attend. The event will allow each to stand in solidarity with the community that shares and bears witness to their experience. If you have a connection to this experience you will be welcomed, whether you have made yourself known previously or not.

To learn more, you are invited to contact Zi Lan Liao, Pagoda Centre Director on +44 (0)7769 330440.

The Liverpool Irish Festival have positive connections with the Liverpool Pagoda Chinese Community Centre. We share communities and have mutual membership of Creative Organisations of Liverpool (COoL). First Take, another COoL member, and Pagoda worked together to create this film, which introduces Peter’s story, which Dan touches on in his article.

We have worked together on a number of projects, most notably when we commissioned The Sound Agents to work on a film (Liverpool Family Ties: The Irish Connection). This documentary shared community stories that arose from a #LIF2018 event that invited dual- and multi-heritage Irish people to share their experiences. Chinese-Irish stories emerged, affected by the forced repatriation. Although details are to be released, it is highly likely you will see this story play out, in some way, at #LIF2021, memorialising the actions and remembering the people affected.

We highly recommend reading Dan’s piece and to supporting Kim Johnson’s -and the Chinese community’s- request for official acknowledgement of this dark chapter in Britain’s immigration control. It is time we recognised and remember the work and legacy of our Chinese community. We seek to put an end to the injustices they face on a daily basis; some historic, some new; all misplaced.

If you would like to support Liverpool’s Chinese community and/or you can offer Kim Johnson MP support in her request, please write to your MP using these government guidelines.

Please feel free to like and share information using the information here on your social media pages or websites. Links to our social media posts are below, which you may share or retweet.

3 Jun event announcement: @PagodaArts hosts @KimJohnsonMP and the ‘left-behind-children’ of 1940s forced repatriation of Liverpool’s Chinese seamen @IrelandEmbGB @CultureLPool @IrishInstitute @IrishCommCare @COoLLiverpool @irishinbritain @ChineseEmbinUK https://t.co/k278qZUd6m pic.twitter.com/eaz0dirmHq

— Liverpool Irish Festival (@LivIrishFest) May 27, 2021

Liverpool Arts Regeneration Consortium (LARC) and Creative Organisations of Liverpool (COoL*) together represent over 30 cultural organisations in the City Region.

Both groups are committed to racial justice and to making meaningful change within their member organisations and in the work they do. Reflecting on the past year, we are now issuing the following shared statement, accompanied by [organisational] links so you can find out what organisations have individually been doing and future plans.

* Liverpool Irish Festival are a COoL member.

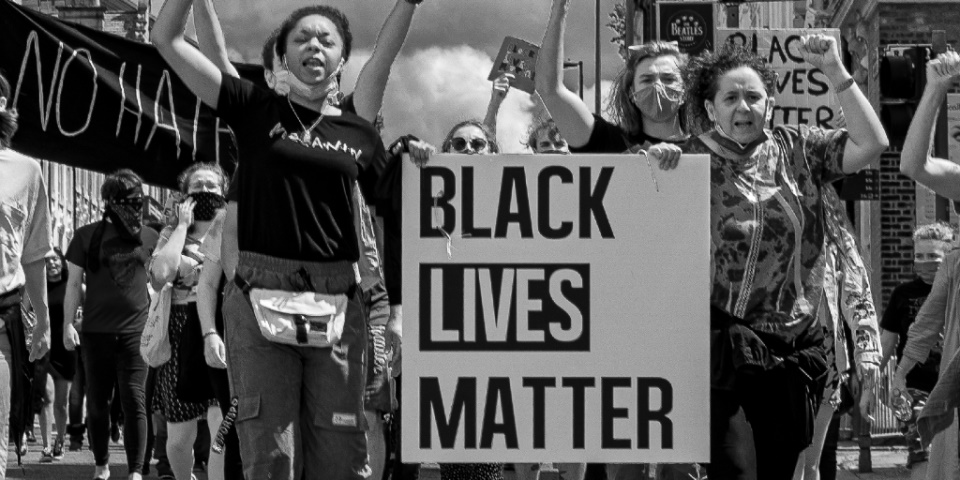

Over a year ago, the cry for racial justice was amplified. Many came together to demand change following the murder of George Floyd. The words “Black Lives Matter” were echoed globally, and people of Liverpool were galvanised to commit to the work of ensuring that Black lives/communities, and the experiences of all those within our diverse communities were fully valued and included. The urgency of this global human right had never been greater, and has been a catalyst for cultural organisations to go through a necessary process of self-assessment and change.

#BlackLivesMatter called for action that would bring about real structural change, not just words or performative social media posts. We are therefore reflecting on our own practices and policies of equality, diversity and inclusion. We acknowledge that harm has been done by previous failings and inaction, and as a sector we are working towards a more inclusive and representative future.

Change is continuous and there is still much to do if we truly want to achieve equity in a society that is impacted by institutional racism. Please click on the links below to see what Liverpool’s cultural organisations have been working on as part of their commitment to change – and what is planned for the future.

See this statement on the Culture Liverpool site.

20 Stories High / Africa Oyé / BlackFest / Bluecoat / Bluecoat Display Centre / Brazuka / Collective Encounters / Culture Liverpool / DaDaFest / dot-art / FACT / First Take / Homotopia / Kitchen Sink Live / Liverpool Arab Arts Festival / Liverpool Biennial / Liverpool Everyman and Playhouse /Liverpool Irish Festival / Liverpool’s Royal Court / March For The Arts / Merseyside Dance Initiative / Metal / Movema / National Museums Liverpool / LUMA Creations / Open Culture / Open Eye Gallery / Pagoda Arts / Paperwork Theatre / Royal Liverpool Philharmonic / Squash Nutrition / Tate Liverpool / The Atkinson / The Black-E / The Windows Project / Tmesis / Unity Theatre / Wired Aerial/ Writing on the Wall

Where links are provided, they lead to the organisation’s work on equality, diversity and inclusion.

#BlackLivesMatter. #SayTheirNames (USA and UK).

#BLM #Equality / Today @LiverpoolARC and @COoLLiverpool stand shoulder to shoulder to

– bring about positive change

– declare our commitment to racial justice

– make meaningful change in the work we do.Read our collective statement in full here: https://t.co/mqmQLM3Rtr pic.twitter.com/2qSAQDkKXT

— Liverpool Irish Festival (@LivIrishFest) May 17, 2021

Each year, the Liverpool Irish Festival seeks the support of city centre and regional landmarks to turn emerald in honour of St Patrick’s Day.

#GlobalGreening was set up by Tourism Ireland and operates internationally. International sites have included: Sydney, Venice, Milan, Hong Kong and Washington DC -and many more- celebrating Irish communities across the world. Turning emerald honours the influence, assimilation and impact Ireland has had and reminds us all of the time, effort and labour of the Irish diaspora.

The Liverpool Irish Centre, Irish Community Care, language and music groups, dance schools and others all have their own activities. As well as these, the Irish Government and Embassy provide various offerings alonside huge events in London, Glasgow and other centres of activity.

To find out more on social media, search the hashtags #GlobalGreening, #StPatricksDay, #FillYourHeartWithIreland and #FeiliePadriag.

We had to wait until the evening of St Patrick’s Day to take our pictures and send our accompanying celebratory messages. Sunset was at 18:19 GMT on 17 March 2021, afterwhich we travelled the region (60+ miles!) taking images of the landmarks that are turning green in honour of the day. Featured in the film below, these sites included:

However, if you have a young one at home and are looking for some post-school fun, My First Focail (Irish Language Learning: https://irishlanguagelearning.com/) have shared some useful play sheets, which you can download here.

Lá Fhéille Pádraig Sona Daoibh go léír!

Over the years, the Liverpool Irish Festival has considered Irishness in terms of creative legacy and production. We have investigated Irishness via dual-heritage lives; the genetic make-up of the city; historic migration and contemporary identity theory (post-Brexit).

Though we have discussed migration and migrants a lot -including causes, diaspora groups and long-term effects- we have given less consideration to modern-day views of domestic migration, or how Irish migrancy is compared to other ‘transient’ communities.

We were contacted by Aileen Bowe, an editor for Immigration Advice Service, who had some interesting points to make on the subject, as well as some thoughts on why arts and culture can help community cohesion.>>

We are all familiar with the nature of the special relationship between Ireland and the UK. The long history of migration between the two countries means that the idea of separate ‘Irish’ and ‘British’ identities has become more blurred for people with immigrant backgrounds.

A common perception is that anti-Irish sentiment in the UK today is at a relatively low rate. However, the reality is that there is not enough evidence to make that claim, in part due to the lack of available statistics on white hate crime. In fact, some Irish communities in Britain have expressed that there has been an increase in sectarianism and aggressions against the community.

Add to this the experiences of people with dual heritages and dual ethnicities and the situation becomes even more complex. There is another prevailing perception that ‘Irish immigrants’ equates to ‘white immigrants,’ but where do Irish immigrants of colour fit into this matrix? For example, how have the influences of Black Irish people in the UK been recognised?

When it comes to tackling the multifaceted challenges of community integration and anti-racism initiatives, it has been shown that one of the most effective approaches is grassroots-driven activism and the work of arts and cultural organisations. These groups provide spaces for people of all backgrounds to reflect on issues and uncover new ways of thinking and cultural expression.

The phenomenon of how second-generation migrants identify themselves is well documented. Studies have found that the motivation for moving has a major impact on how well new migrants and their families assimilate into the new country and its culture.

Traditionally, many Irish people have migrated for employment and a better quality of life, which was not necessarily always a free choice. Conditions in Britain were sometimes harsher than in Ireland, meaning that generations of Irish people suffered from high levels of poor mental health and excess mortality rates.

A 1996 study found that in the second-generation Irish population in the UK, there were “significantly higher” mortality rates when compared with the wider UK population. The authors drew the conclusion that there was evidence of enduring challenges caused by the lived experience of being in the UK, as well as socioeconomic, cultural and lifestyle factors.

Although it might appear that British society has had the bigger impact on Ireland, it’s undeniable that Ireland has shaped the culture of the UK. From the high number of Irish musicians studying and performing in the UK, to beloved television personalities, fashion designers, chefs, and artists, there has been a major contribution to the British arts and cultural scene from Irish emigrants.

Despite the fact that nowadays only between 1-3% of the Irish population speak Irish daily, with the vast majority of people in Ireland speaking the language of the British colonisers, there are many instances of the influence of Irish on the English language (think ‘brogues,’ ‘hooligan,’ ‘phoney,’ and ‘whiskey’).

Known as the ‘second capital of Ireland,’ Liverpool is one of the best studied regions of Irish immigration to the UK. With an estimated 50%-75% of Liverpool residents claiming some Irish connection, it is fitting that Liverpool is today held up as an example of the many positive benefits of integration. However, this was not always the case.

Known as the ‘second capital of Ireland,’ Liverpool is one of the best studied regions of Irish immigration to the UK. With an estimated 50%-75% of Liverpool residents claiming some Irish connection, it is fitting that Liverpool is today held up as an example of the many positive benefits of integration. However, this was not always the case.

While it can sometimes be tempting to focus on the contributions of just the Irish immigrants to Liverpool and the UK, it is undeniable that immigrants from all around the world shaped the UK in multiple, many faceted ways.

Whether it’s the contribution of healthcare workers, new influences on food and drink, the many contributions from scientists, and the artistic impact of people from diverse nationalities – the UK as a whole could be considered a shining example of the benefits of immigration and integration.

However, one point that is important to consider is how people from certain immigrant backgrounds were viewed as being more or less ‘worthy’ than others. The current discourse in the tabloid media is a binary view of immigration as being harmful for UK citizens as a whole, with Britain’s exit from the EU being cited as one of the outcomes of this harmful rhetoric.

Indeed, even today in official Gov.uk materials, “taking back control of our borders” is cited as one of the main reasons for the UK leaving the EU, with the unspoken implication that the border had been overrun or hitherto outside the control of immigration authorities.

It is probably quite logical that a country that colonised 90% of the world is today overly preoccupied with its own borders, especially one without a strong understanding of its history (evidenced by the fact that 59% of the UK population believe the Empire was something to be proud of). In fact, a common theme across anti-migration sentiment is a sense of dissonance and disengagement from facts.

The often-dehumanising process that migrants must undergo in order to enter or stay in another country is reflective of how attitudes to immigration and the parameters of what is acceptable and not are constantly shifting. As all Irish people know, the Great Famine destroyed the country in many ways, essentially halving the population from 8 million to under 4 million (from which it has never recovered, and is the only European country to have a smaller population today than in the 1800s).

There have been arguments that the Famine was a genocide committed by the English, but this has been debunked by historians. What is undoubtedly true, however, is that the British government failed to put in place measures that would have alleviated the starvation of the poorest people in the country, resulting in hundreds of thousands of preventable deaths.

And so, it was Irish migrants who came to the UK to escape poverty and starvation, but who were treated poorly and until relatively recently, had poorer life outcomes than UK-born citizens.

In a world where colonisation has touched almost every area of the earth, the overwhelming media portrayal of migrants is from a negative lens.

Organisations like Irish in Britain and the Liverpool Irish Festival have been doing stellar work in raising the profile of Irish immigrant communities and challenging the narrative of the ‘lazy, uncultured migrant,’ who ostensibly adds nothing to the host country.

Organisations like Irish in Britain and the Liverpool Irish Festival have been doing stellar work in raising the profile of Irish immigrant communities and challenging the narrative of the ‘lazy, uncultured migrant,’ who ostensibly adds nothing to the host country.

These programmes serve as important institutions that provide an alternative perspective to the mainstream portrayal of immigrants in the media and popular culture.

Despite the extensive studies into the topic of migration, there is a hard-to-challenge perception that some immigrant communities are acceptable, while others are less so.

For some Irish immigrants in the last 50 years, they have had the advantage of appearing British, with skin colour and language being less of a barrier than some other nationalities.

“They (the Irish) live on beasts only, and live like beasts. They have not progressed at all from the habits of pastoral living…This is a filthy people, wallowing in vice”- Gerald of Wales.

The language used here by a historian around the year 1188 is not dissimilar to the discourse applied today to people emigrating to the UK or around the world. Interestingly, some historians believe that Gerald wrote such an account as part of an effort to gain favour with King Henry II and justify his invasion of Ireland.

The role of social media in amplifying anti-immigrant attitudes is a topic that is frequently researched, but it is also important to consider how language is framed by supposedly reputable news organisations, and how this filters down to individual groups online.

A seminal 2008 paper into the discourse around refugees, asylum seekers, immigrants, and migrants (RASIM) in the UK press found that the media overwhelmingly framed these groups into some common negative categories. These categories included suspicion around the legality of their entry into the UK, economic burden, economic threat and the return of these people to their country of origin.

While the study found that 98.1% of tabloid mentions of RASIM were negative portrayals, the ostensibly more objective broadsheets published negatively focused articles on this topic 75.6% of the time.

As in the case of Gerald of Wales, it is worth considering whose agenda it serves to push anti-immigration rhetoric and foster distrust against migrant populations.

Community organisations showcase not just the benefits of immigration for the host country, but also focus on shared values, such as arts and culture, applying a progressive lens in advocating for the dignity of all community groups.

Similarly, Liverpool Irish Festival consistently shows strong support and solidarity for groups that may be facing inequalities or prejudice. For example, the organisation was quick to offer direct support to the Chinese community in Liverpool following the start of the global COVID-19 pandemic, when there was a significant increase in hate crimes against Asian communities.

Not all groups of people face the same inequalities: some face much worse conditions than others. It is important for all communities to help raise each other up, especially those groups who have undergone poor treatment themselves in the past.

With the dual challenges of COVID-19 and Brexit likely to impact on the UK and its inhabitants for the foreseeable future, it will be important to bear in mind that there are more elements that bring people together, and attempts to divide communities should be steadfastly rejected.

The ultimate goal for most people is to live a happy and peaceful life. When people from different cultures come together to share their life experiences and their ways of life, incredible things can happen. When you have more open-mindedness, tolerance, and empathy in a community, the stronger its ability will be to provide space for growth and development for each member of that community. Ultimately, no matter a person’s background, living in peaceful co-existence is something that everyone should strive towards.

<< Aileen Bowe is a writer and correspondent for the Immigration Advice Service, an organisation of immigration solicitors that provides legal aid to forcibly displaced persons.

Like Aileen, it is our inate belief that by sharing creativity and culture; creating safe spaces for discussion and hearing one another; we can build stronger, safer, more connected communities.

The above article has not been fact-checked -nor does it necessarily present the precise views of the Festival- but it is presented here as a thought-piece by a collaborator we believe has an important point to make and a specific vantage that many of us are not permitted.

If you have papers you would like us to consider for the website, please email us at [email protected].