Liverpool Irish Festival present a newly commissioned song -These Roads- from Úna Quinn and Neil Campbell, commemorating An Gorta Mór.

Liverpool Irish Festival present a newly commissioned song -These Roads- from Úna Quinn and Neil Campbell, commemorating An Gorta Mór.

#LIF2023 Chair and musician, John Chandler, takes readers through the trad sessions avaiable across Liverpool (Aug 2023).

Lisa Lambe interrogates Nightvisiting; a show about rural Irish hearthsides and collective cultures post-1850s and pre-1940s electrification.

A £1,000 commission is available for a creative project, centred on Irish and/or Gaelic creativity, to form part of #LIF2021.

Kilkelly is a project led by Irish singer-songwriter Conor Kilkelly, based in Berlin.

With collaborators from the city’s thriving “Dark Folk” music scene, Kilkelly released debut album The Prick & The Petal last year, which was showcased in full at #LIF2019, with accompanying art book by collaborating artist and Kilkelly vocalist, Stephanie Hannon. This year we catch up with Kilkelly and Stephanie, plus the character narratives conveyed in the concept album, centred on “depravity, desperation & desolation” of Old Catholic Ireland, following The Famine. Combining a piece written by Conor – portraying his personal struggles within his musical themes- Stephanie interviews Conor and poet, Ciarán Hodgers, who hails from the same Irish town as Conor; Drogheda on the East Coast of Ireland.

The most severe punishment given in our prison system is social isolation. When an inmate is considered too dangerous, too volatile within the highest securities prisons they are confined to a room; sometimes for 23 hours a day for the remainder of their imprisonment. Similarly, a tribe’s most severe punishment is banishment.

In a death sentence, the punishment ends as soon it is instigated; by definition it is short-lived. In isolation and banishment the punishment is sustained and so is –arguably- greater.

In Kilkelly’s debut album The Prick & The Petal we met the characters Joe and Mary; unhappily married, marred by addiction and poverty. In the album we heard how they isolated from each other; viewing the traumas of their day whilst aimlessly traversing through old Catholic Ireland with vague hopes of finding solace somewhere across the seas.

This self-banishment to ostracise oneself through emigration is at the heart of Irish cultural identity. Historically it was a last ditch attempt at survival, but the path is a punishing one. Those who leave today are not doing so to ensure they can feed themselves. What, then, drives them to consider dropping everything, cutting ties with their homeland? For artists, is it a case of the survival of their craft?

As James Joyce said, contemplating his own emigration, is Ireland “the sow that eats its young?”.

Conor’s Story

When asked why I moved to Berlin, I never had a good answer. I truthfully didn’t know. The most I could muster with any sense of conviction was “on a whim”. The vagueness of my answer eased the inquisitive look on the face of whoever asked, and appeased something in me, too. “A whim”; why not? People find nothing more romantic than falling in love at first sight; why not the same for falling in love with a city? When you fall in love it’s only a matter of time before you move in together, after all.

Granted, my first love was always Galway, on the West Coast. I’d an on-off, hot-cold relationship with my hometown of Drogheda and became enthralled with Galway once I moved away for university. Cobbled streets; charm; sea; rivers and countless pubs of all sorts and sizes… a thing of beauty. But, after five years, we split (“it’s not you, it’s me”); I sought the greyer pastures of Dublin, somewhere bigger; where “the action was”. And I loved Dublin, too.

What pained me was her price. “How can anyone afford to do anything here?”, I scowled in thought of forking over 20 euro to the taxi-man at the end of another night out in the city. The buses stopped at around 11.30pm. The good music didn’t stop till 1am. Hence my problem. A big one.

In my last year of education my part-time job was as a campus tour guide at UCD; money was tight to the point of asphyxiating.

When visiting friends for a few days in Berlin that year, I simply couldn’t fathom how good they had it. Their beautiful high-ceiling apartment was chockablock with what could be described as “artsy types” and political radicals; the types my friends would mock and I would salivate over when we caught sight of them out in the wilds of Dublin city, usually over at The Workman’s Club (a local hipster hangout).

“What do you do, Conor?”, a strikingly beautiful lady asked me, perched on the stairs to a bed hanging from the high ceiling. “Philosophy. And I tour guide at a university in Dublin. You?”. “Tour guide? Yes, I’ve done some of that, but at the moment I’m helping out setting up art installations, in between exhibits. I have one of my own coming up shortly.” An actual artist; I never met one before. Sounds ludicrous. Sure, I’d met many a-dabbler, but a working artist? Unheard of!

The party’s tone turned as the anarchists laid out the plans for the following day. The friends I’d been visiting were caught up in some trouble at the hostel they’d worked at. The trouble being: they worked for two months, and now the owner has fobbed off all payment simply stating he hadn’t the money to pay. I asked Laura, my Irish friend, what exactly happened.

“We’ve been shafted of two month’s pay. We’ve been given nothing since we arrived!”.

Okay, I thought –turning on a heel- maybe Berlin isn’t so great.

The next morning there I was: placard in hand, amidst a parade of anarchists, confused and excited. The majority of us derived from a group called Basta, who provided free legal aid and served as foot soldiers to picket the hostels and other dubious organisations, when their services were needed. Eventually the protest was effective enough to bring down the whole business, making headlines nation-wide, and leading to legal proceedings and an out of court settlement.

For the time being, we -a 70-strong group- marched and howled and roared and ranted, in and about the building. It seemed to have endless nooks and crannies; we darted in and out of rooms, getting lost and seeing absolutely nobody –all the while and demanding our rights– well, Laura’s and Daragh’s, anyway.

When the fuss was over, and placards dropped, I asked Laura how we’d get home, as our marching brethren dissipated away. “You’re never more than ten minutes from the underground. Don’t worry Conor, we’ll get home”. “What time does public transport stop?” I asked, “Stop? It doesn’t.” she replied. And, so, then and there, my fate was sealed. I was a Berliner. No more 2am taxis sapping my funds. I would be anarchist, artist, Berliner! Not so much a whim then, as an economic and cultural necessity, or so I thought. And that seemed to be the truth of it until a friend, who came to visit, asked me the simple question: “If you could have been an artist at home, would you have stayed?”

The question irked me -as all do that touch a vital nerve- especially one you’ve not addressed yourself. Stephanie (SH) suggested we prod further into the discomfort…

Interview with Ciarán Hodgers (CH) and Conor Kilkelly (CK)

Ciarán Hodgers, Liverpool based poet from Drogheda, Ireland, remembers the day he arrived in the UK: “I remember [thinking] ‘there is no one I know touching this earth’. The land beneath my feet touches no one I know … it was the right balance of terror and [liberation]”.

SH asks CK and CH about Drogheda their experiences of hometowns:

CH: [It was] a post-industrial working-class town with the symptom of being next to the capital city. It’s not good enough; it’s the second child… it gets a bit ignored.

CK: Both my parents were from the west of Ireland, so they didn’t have the Drogheda accent. When I went outside, everybody had a Drogheda accent, but when I came inside, and it wasn’t the same… And the telly had a different accent as well… my childhood experience of my surroundings was confusion… I kinda always felt like I was an intruder.

CH: Imposter syndrome is a working-class pandemic. [It} affects us forever. I don’t think we ever really get over it. I think that adds to our sensitive dispositions [making] us feel like we don’t belong.

SH: Do you feel compelled to escape a sense of “Irishness”?

CK: I didn’t know what Irish was. It was just ‘Drogheda’, I wanted to escape that. Maybe Irishness too. … I remember kind of choosing the accent I wanted. And it was the telly accent. I thought ‘if I talk like them, I can blend in with [the Americans] once I go there’. It was a conscious choice, except from a 6-year-old.

SH: What is Irishness?

CH: I think Irishness is hugely changing now. Being Irish wasn’t cool when I was growing up, which might have led to some of those escapist tendencies. One thing that really defines the Irish experience is the church and state conversation. It’s becoming unpicked and in that gap is the new Ireland of young activists. Non-religious… I don’t think we can understand Ireland until we leave it.

SH: Were you aware of all of those things (church and state) when you decided to leave? Did those things contribute to your decision?

CH: Growing up queer, I wasn’t welcome or safe inside religious spaces. That was the confirmation I needed to say ‘thank you and goodbye’. So, I have an interesting perspective of watching it improve. Watching religious ground become more queer friendly, or antiracist or more welcoming for refugees, that’s really exciting for me. That’s new Ireland.

SH: But how do you feel looking on from a distance?

CK: When I left I instantly became very protective of Ireland. I didn’t fall in love with Ireland until I left. I had time to reflect; how lucky I was to live somewhere so beautiful and the kindest souls I ever met were all Irish. I didn’t know any of this, because I just took it for granted. [I] fell in love in Galway by being away from Galway; and then I was like an evangelist for Galway. It took me moving to Berlin to find the same pride for Drogheda. I still had mixed feelings about my home town. If someone is convinced that where they have lived their entire life is the best place on earth, they aren’t qualified to give that opinion.

SH: Has Irishness been present in your creative work?

CK: I can’t write a song without Ireland somehow creeping into it. It’s almost as though “Irishness” is my muse. I have other muses, but that one is always there. It’s so fundamental and foundational to what I do. Now I’m proud that my songs are considered Irish folk songs. It’s actually an honour to do something that’s considered remotely Irish Folk. That feels great to me. It’s a badge of honour

CH: Because my art form is spoken, I think I can get away with quite a lot because I have a different voice. {laughs}.

SH: Is ‘leaving’ intrinsic to Irish culture?

CK: During the famine, half the country either died or left. There’s millions of songs that talk about loved ones gone away. In a way, I’m just carrying that tradition.

CH: It’s like it’s in the DNA… there’s science on this regarding the children and children’s children of concentration camp survivors having different DNA because of the mental health trauma their ancestors experienced. It has to affect the family tree moving down.

So leaving is literally in our blood?

Conor’s Story (continued…)

It wasn’t until I was writing my debut album The Prick & The Petal showcased at #LIF2019 that I did a second take on my practical assessment of leaving my mutterland, as the Germans say. The sense of loss was blatant in the songs; omnipresent throughout the ballads and laments coloured throughout the album.

I never set out to write anything in particular when I write. If I do I find the end result plagued with pretension. The last thing you want -when delivering something meant to encapsulate a truth, an emotion- is pretence. All you can hope, for when you take your pen from the paper, is that the ink set within your notepad won’t make you wince in years to come. The only way you can ensure this, is by not lying to yourself. Like a teen diary trying to sound cool, instead being utterly insecure. You’re only hope in song-writing is that you can decipher your innards: heart and gut. I let the gurgles and thumps speak for themselves.

Half way through my crafting The Prick & The Petal I realised this compilation of songs about my life -my troubles, my loves, my losses- was in fact, not really about me. Well, not, solely about me anyway. It was set in Ireland. There were characters that re-emerged. They held addictions I’ve never faced directly; fears I’ve never had materialise. Though all true somehow, they gurgled and thumped out, without me having to undergo the specifics. There were two characters: Joe & Mary, two star-crossed lovers (it seemed to me), within the songs. When ordered the right way, the songs played out like a story – one of isolation, emigration, depravity, religion & loss. It was an utterly Irish story – written in parts of Germany, Ireland, London, but truly Irish nonetheless. But it was someone else’s story. What right did I have to speak it? Who were Joe & Mary?

I’m still not entirely sure. But, I know -looking back at it- I don’t feel the wince on my face I feared I would. It rings true for me still when I play it live.

There is something in the album that is about Ireland’s story of emigration. There’s something in it true to my story, too. Above all, there’s a longing for home in it. Why then did I leave home? It couldn’t be just a whim.

It couldn’t be something as trivial as economics, could it?

A year on, I am reeling with this question. I still don’t know for sure, but the gargles and thumps of the laments of the two star-crossed lovers, who again and again, persist in these songs; they had no choice. “The jobs dried up and my nerves grew thin”, something in it -that line from the open track of album- still touches a nerve. Like the truth always does.

The Liverpool Irish Festival would like to sincerely thank Conor Kilkelly, Stephanie Hannon and Ciarán Hodgers for their contributions. We asked a lot of them to self-question, commit to paper and share their feelings, skillsets and experiences, with us, at a time of great difficulty for everyone unable to get home. We’re very keen to bring Kilkelly back to another Festival and hope you will follow their story with us.

We highly recommend the album and art book (with beautiful art works by Stephanie Hannon, as well as the CD album), available here: https://kilkellymusic.bigcartel.com/product/kilkelly-the-prick-the-petal, along with Ciarán’s poem How to be an Irish Emigrant and Kilkelly’s new video for Anywhere Buy Here Will Do (below, final entry) made to reflect migrant’s eyes in a new land. Their lockdown documentary: Kilkelly Live Inside is below.

https://youtu.be/3hgHisazZBg

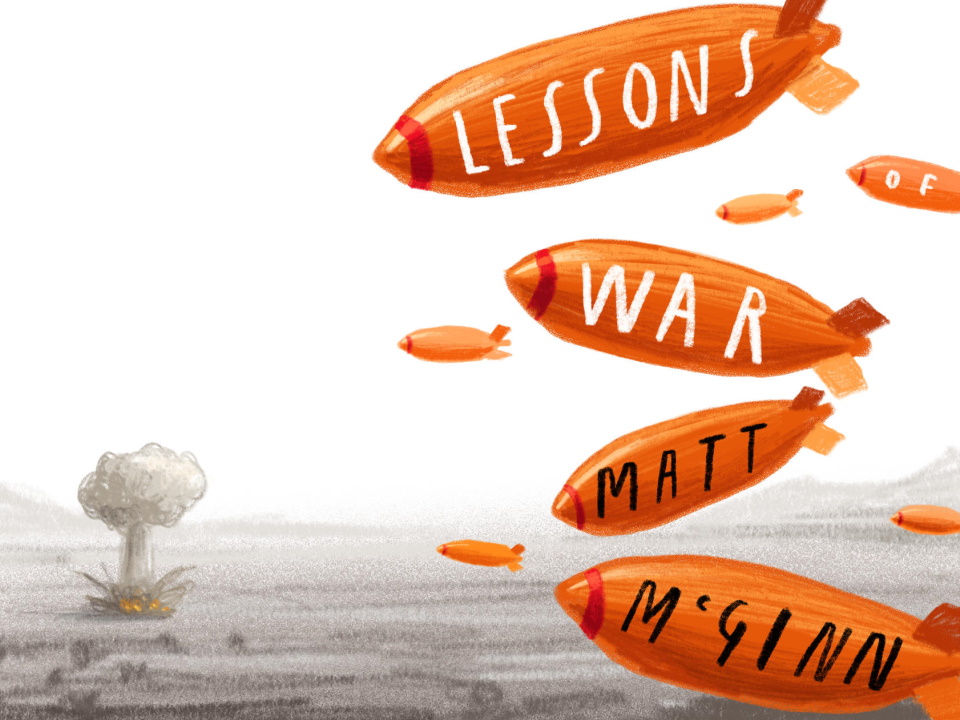

One of the big lessons I will take away from Lessons of War is the recognition that how I grew up wasn’t exactly normal…

I’m from a small village in Co. Down, in a place sometimes referred to (even by myself) as Ireland, Northern Ireland, the north of Ireland… How I name it depends really on who I’m talking to. Sometimes it’s to make a point about who I am. Sometimes it’s to make the person I’m talking to feel at ease. Sometimes it’s just the easiest way to say it so it doesn’t require any further explanation.

And there was another lesson… When you grow up in an environment of conflict, it can lead you in a few ways. One way might be to make you hard; make you staunch and immovable. Your opinion is pretty much ‘the right way’, no ‘ifs’ or ‘buts’. I think I went a different way; I moved and shaped myself into my surroundings and adapted to suit whoever’s company I might be keeping. Was this the right thing to do? Probably not, but neither was the former. It was a matter of making life a little easier for myself. Survival, I suppose.

Don’t get me wrong, though; the little nook nestled into the Mourne Mountains was a lovely place to grow up, and was pretty sheltered from The Troubles compared to other parts of Northern (let’s just call it that for now) Ireland. I think it was my ability to adapt that gave me a keen knack for empathy. Empathy comes in handy for writing songs in general, but for this project –Lessons of War- I think it allowed me to access the experiences of other musicians and artists, from areas across the world, also divided or affected by conflict. That’s what Lessons of War is about.

I come from a family of hard workers and I realised that if I wanted to pursue something personal, it was probably best to involve it in my work, or else it’d forever find itself at the bottom of the list. I knew I had issues that I wanted to address and found that by connecting with artists facing similar issues across the world, it might help me learn a little about myself.

It was probably no coincidence that -around the same time- I had been feeling stirred-up by what was happening in Syria and with the Refugee Crisis. I had bought my first smartphone. Avoiding the six o’clock news all my life was my means of escapism. All of a sudden, world news was smacking me in the face thanks to social media. It awoke an anger in me that I hadn’t felt in quite a while. As international powers bombed Syria, I realised that people in power seem to never learn from the mistakes made by their predecessors. Listening to a radio show, a caller wondered “would it not be better to send in a negotiating team and figure it out”? The host of the show simply laughed at the caller’s suggestion as “unorthodox”. I was raging, but you know he was probably right. How many times have we witnessed the first act of a government entering conflict be ‘strong’ and heavy handed? Negotiation is often overlooked when it should be the first port of call.

…But then, I suppose to negotiate you need charm; and not the smarmy, sickly, schmoozey, charm of most politicians. Proper charm. The Irish have it. And I tell you what, the people of Liverpool have it. It’s the charm of the courageous. It’s the charm that allows you to stand in the middle of a knife-fight armed only with a smile and a gallon of wit. It’s the same charm that allowed four lads from Liverpool take over the world. It’s not something that’s taught. It’s a vibe…it shakes through a community. It’s a precious thing that I’m so proud to say we share.

So back to 2017. I took a simple idea to the Arts Council of Northern Ireland. The plan was to assemble artists from areas of conflict across the globe. We would create a music video, each of us performing to a song I would pen that spoke to the futility of war. After trawling through the internet for days most artists I approached were very open to the idea, namely Haris from Bosnia and Herzegovina; Seydu from Sierra Leone; Yazan Ibrahim from Golan Heights and The Citizens of the World Choir, based in London and made up of refugees and their carers. The easy part was now to write the song. Every time I sat down to write, I couldn’t. Fear stopped me each time as I knew it was opening parts of my brain that I thought I had welded shut, and in procrastination I wrote and released a full album titled The End of the Common Man.

I had to return to my original project, though, and get it finished. I had to get my eyes opened and so interviewed as many people as I could who knew conflict first hand. There was Tommy Sands, a man who has sung for peace for many decades. Richard Moore, lost his sight when he was hit by a soldier’s plastic bullet on the streets of Derry as a child (and as a result created the charity Children in Crossfire). Mark Kelly, a music manager and audio specialist who lost his legs to a UVF bomb in his youth (and helped develop the WAVE Trauma Centre in Belfast). Elke Rost, from a town in Germany called Mödlareuth that was split in two overnight by the Berlin Wall, cutting of a generation of families and friends.

I finally got the song written, Lessons of War. Each artist did their part amazingly. But now that I had opened the flood gates, the songs kept coming, and as word got out about the project, other Irish songwriters wanted to try their experiences. Before long I had a full album of anti-war songs with contributions from Mick Flannery, Ciaran Lavery, Malojian to name a few. Of all the musicians I had used on the first song, Yazan Ibrahim was incredible, a young virtuosi Flamenco Guitarist from the Golan Heights that borders Syria. I brought him to Ireland. We locked ourselves away for a week with some of Ireland’s best session musicians.

The album was finished, and with it a documentary; local film maker Colm Laverty shadowed us most of the way and created a very powerful short film as a result. Win!

I was so excited to be taking Lessons of War to Liverpool this year for the prestigious Liverpool Irish Festival. Some of the players I had gathered together were some of the most amazing talents I know. And with you people of Liverpool cheering us on, it would have been a glorious show. Unfortunately, as Covid-19 hit it was not to be. It’s the right choice, the safe choice, and we know we’ll meet again. Both you and I are very lucky that your festival is run by one of the most generous and hardworking people I’ve come across in my many years of playing music. We will work together to best whet your appetites for 2021 by giving you a unique online version of Lessons of War. Hopefully it means that we all can come over there next year and take the roof of the place. Until then, you beautiful people of Liverpool, keep yourselves safe and well.

When we land once again in your beautiful city, we’ll make sure to have a night off booked and have a proper session, too. Slan, Matt McGinn

Book your place at ou event with Matt on 22 Oct 2020.

As Matt alludes above, working with the Liverpool Philharmonic, we were all set to bring Matt and Friends over to do a Lessons or War live music night. Sadly, in 2020, this was not to be. Instead, we will watch his beautiful documentary (LINK), which covers the making process of the album, before joining him on Zoom (LINK) to discuss the music, the experience and the opportunities that can be found in sharing, collaborating and putting a little generosity out in the world. Fingers crossed, we can see him in person during #LIF2021.

Thanks go to Matt McGinn, Richard Haswell (Liverpool Philharmonic) and Terri O’Brien for a lot of behind the scenes work, that will never see the light!

The River Festival returns this summer with a bounty of treasures for landlubbers and seafarers alike.

Liverpool Irish Festival are proud to have been recommissioned by Culture Liverpool to produce events for this showcase. We have a raft of music on board La Malouine, a series of dance delights for the Martin Luther King Jnr stage and other sessions for Salthouse Quays. We’ve got shanty singing, bands and acoustic sets open to all. Everyone is welcome and we hope you will enjoy the River Festival’s tall ships and variety of brilliant and engaging works, which include: giant sea urchins, a view of the earth (Gaia), the Bordeaux Wine Festival, Indian dancing (Milapfest) and even shipwrecks (more here).

You can see our own event listing and schedule for Sat 1 and Sun 2 June 2019 using this link. Meanwhile, biographies for all those involved in Liverpool Irish Festival programmes can be found below.

Anti-Shanty is an international singing ensemble based at Liverpool John Moores University, specialising in sea shanties (ship-board work songs from the nineteenth century) associated with Liverpool. As their name suggests, Anti-Shanty retain a slightly less than reverend attitude towards the tradition, and are quite happy to mix things up a bit, genre-wise. They say singing is good for the soul; singing Liverpool-based sea shanties is even better. Come and sing along with Anti-Shanty!

Celtic Knot Ceilidh Band have played together as an instrumental folk band for over a decade and focus on Irish, Scots and English Ceilidh msuic. With toe tapping tunes, brilliant energy and often a dance caller, you can be sure of a great atmosphere when listening to this group.

Former Beatelle, Catherine has been a regular on the Liverpool music circuit for over a decade and has played n some of the most prestigious Beatle’s events around the world, including five International Beatleweeks. After starting a family and taking herself solo, Catherine performs weekly in several Liverpool venues focusing primarily on either Irish Traditional songs or music from the 60s, ranging from Del Shannon, Bob Dylan and some old Liverpool heroes.

Established by George Ferguson (World Champion 1972), this dance school participates in many events throughout the year, representing Liverpool’s strong connections with Irish traditions. As proud ambassadors of Ireland’s rich heritage, they have appeared on numerous TV and theatre shows. Catering for all levels of dance -from beginner to advanced- George always provides the first class for free! His dancers are some of the best and you can always be sure of interesting commentary of the history of the dances as well as exceptional quality dance. Details are available on Facebook (+44 (0)7771884724).

Jo and John play together as music instructors for Melody Makers. Jo is an exceptional fiddle player (known for leading the Giants around Liverpool on a truck of violins to over a million visitors) whilst John’s specialisms are guitar and mandolin. Both are experienced folk musicians and play numerous other instruments and in groups including Cream of the Barley and Calico, celebrating their Celtic roots. Their music blends traditional and contemporary styles to create their own mix of songs and tunes, which ensures the Celtic tradition is alive here on Merseyside. They are delighted to be performing at this year’s Mersey River Festival.

Audiences everywhere rave over the harmonies of Kimber’s Men, having appeared at festivals across Europe and the UK, twice on Sunday Brunch (Channel 4) and on BBC2 and 4’s production of Sea Songs, with Gareth Malone.

John Bromley is a folk song singer, guitarist and solo artist, additionally playing whistle and bodhrán. Neil Kimber plays guitar. Neil and Ros Kimber composed the wonderful song ‘Don’t Take The Heroes’, now sung by shanty bands all over the world. With a powerful and bluesy voice and accomplished guitar skills, Gareth Scott brings another dimension to Kimber’s Men’s sound. Steve Smith (sound engineer) recorded and produced their latest album and -as multi-instrumentalist- completes the group with his high harmonies. Expect to laugh, sing and be generally entertained.

Mick O Brien (Wexford), Gary Lawlor, Paddy Mangan and Zak Moran (all from Kildare) make up The Druids, an award-winning Irish act, on a nationwide tour, celebrating 10 years of gigging. Winners of the best live act at the Irish Folk Music Awards 2017, they are in high demand, constantly internationally, throughout Europe and the UK and bringing their unique style and passion to some of Ireland’s greatest folk songs and stories with expert musicianship, vocal ability and performances. Established and based in Co.Kildare in 2008, The Druids are a household name in Ireland.

“The Druids entertain and educate while having the audience on their feet”, Patrick Johnson, Irish Music Cafe radio show; Detroit, Michigan, USA.

The Folk Doctors are Merseyside/Irish duo John Armstrong and Ultan Mulhern. The band grew out of a collaboration on a song –No Place I Call My Home– for the Liverpool Acoustic Songwriting Challenge in Autumn 2016. John composed music for Ultan’s lyrics and performed them on the recorded entry. Spin forward to release of Silent Shores in 2017 and you start to hear their incredible storytelling unfold about builders and soldiers, rainfall and whistle-blowers, lucky beggars and the downtrodden.

“”To breathe in the air of Silent Shores, [is] to know that for a time the only company you have, and need, is your own thoughts and a great Folk album playing in your ears”, Liverpool Sound and Vision.

The Wee Bag Band’s raison d’être is to bring mad, bad, trad, popular and contemporary Irish Celtic music and song to the masses at pubs, clubs, parties and festivals, primarily in North Wales and the UK. However, their music has taken them to many parts of the world including the UK, France, Switzerland, Spain, Germany, USA, Cuba, Bahamas, Puerto Rico, Honduras and even northern Greenland. This is a real high energy team, with lots of laughter ringing out between members and audiences!

Only Child

Only ChildOnly Child have released two albums and two EPs since 2012. The band have headlined Liverpool’s The Music Room, View Two Gallery, The Zanzibar Club, The Magnet and Thornton Hough Village Club in Wirral, alongside high profile support slots with Blue Rose Code, Pete Wylie, Gemma Hayes, Ian Prowse and Amsterdam, Steve Pilgrim, My Darling Clementine and Mick Flannery.

“Only Child tell stories that ask questions, pose problems and attack the establishment […] “, The Thin Air, April 2016.

These presentations are commissioned by Culture Liverpool from the Liverpool Irish Festival. We are delighted to be involved in this wonderful event and grateful for the City Council’s continued support.

We asked long-standing Liverpool Irish Festival friend Gerry Ffrench to give us some information on her roots and current work, ahead of a performance of self-penned music and songs over at the Albert Docks for the Three Festivals Tall Ships Regatta (the late May bank holiday weekend 2018).

Gerry has sung in festival sessions and in 2017 played Master of Ceremonies for our Visible Women evening, over at the Philharmonic Music Room, introducing Emma Lusby, Mamatung, Sue Rynhart and Ailbhe Reddy. We regularly talk about the books that Gerry has planned, stories from her father’s life and the incredible influence of Irish history of Liverpool life.

Gerry is the winner of Folk Northwest’s talent showcase, which took place at Costa del Folk Portugal in 2017. A singer songwriter from Liverpool, Gerry has strong family links in Wexford and Mayo. She is a popular performer in folk clubs in and around Merseyside – and the North of England – as well as appearing at various folk and shanty festivals here and abroad. Currently working on her third full studio album of original songs in Angel Valve Studios Oxton (Birkenhead), Gerry uses the stories of ordinary people of the city – past and present – as an endless source of inspiration for her songs.

Gerry’s new album, Rivercity Echoes, runs as a succession of stories, intertwining Irish and Liverpool life. Rivercity Echoes will have eleven original tracks, all composed, sung and played by Gerry with almost every track telling a story. Through these stories, Gerry speaks of times gone, of love and loss and of today. Below is a breakdown of those stories, as described by the artist.

When Paddy Came Marching Home is about a whacky Irishman who in 1939 joined the Royal Navy, didn’t like it, so enlisted in the army while on leave, eventually fighting his way from North Africa all the way to Germany.

Do Your Washing for a Penny was inspired by the great Liverpool Irish philanthropist Kitty Wilkinson*, originally from Derry, who was instrumental in setting up wash houses in the slums of the city, after saving many lives during the cholera epidemic of the 1830’s.

* #LIF2018 features a play on this subject, by Carol Maginn called Kitty. To keep up to date with our programme (announced from summer), sign up to our mailing list. We usually send no more than one mail per month, rising nearer to the festival with event news. We never sell any data.

The Admiralty Regrets is the half-forgotten story of the Thetis Submarine disaster in Liverpool Bay. It was triggered by seeing 99 men’s names on the steps of the bell tower in Birkenhead Priory, right next to Camel Laird’s where the sub was built in 1939.

I wrote My Brother’s Shoes after seeing a pair of combat boots, left by a veteran, at the Vietnam War Memorial in Washington DC seven years ago.

Dorothy Drew retells the story a popular traditional folk song The Callico Printer’s Clerk – from the point of view of the female protagonist.

Bound For Glory was written after a fan suggested I check out the history of the Isle of Mann Packet ship The Ben Ma Chroidhe, which sank off the coast of Turkey during the first wold war.

And so it goes, although not all of my songs are about the past, I – like Santayana – believe that “Those who cannot remember the past are doomed to repeat it.”

The Liverpool Irish Festival would like to thank Gerry for giving this exclusive insight in to her new album! What a treat for us! To find out more and to keep up with Gerry’s album release make sure to follow her on Facebook, search for “Gerry ffrench, Folk Singer” or visit her site: http://gerry.helloplaza.uk/