This article features Cal Freeman and Chloe Muldoon, respectively director of and actor in Hold the Sausage, a short film featuring at #LIF2021.

This article features Cal Freeman and Chloe Muldoon, respectively director of and actor in Hold the Sausage, a short film featuring at #LIF2021.

This is a photo-story from young photographer Oisín Askin, called Saol (Life). We believe he is 'one to watch'.

Open call for Irish designers/applied artists to submit work for In the Window, an October exhibition at Bluecoat Display Centre for #LIF2021.

We began work with Alison Little in 2016 when we first launched our In:Visible Women programme. A Liverpool based artist, activist and educator, Alison’s work layers texture and printed evidence against abuse and empowerment.

Following on from the in memoriam work the Festival did with Eavan Boland’s poem Quarantine in 2020, Alison has created a visual response to this work. Working with physical materials to draw on the emotional experiences of the people within the poem, and the millions they have come to represent. We are presenting this work on St Brigid’s day as a female led-work, but also as a story that connects with St Brigid’s work for equality, as we continue to stave off disease, work together as a society to cure our ills and come to understand our history.

What we present below is a short ‘making of’ gallery of Alison’s process, making the installation, followed by images of the installation ‘in the field’, in both the snow and wet of January weather.

Alison’s work is all the more poigniant having fought off Coronavirus herself, but who lost her partner to the virus. Our condolences go to her and their loved ones and our thanks go Alison for her courage, creativity and commitment.

You can hear and read Eavan Boland’s Quarantine. here.

Installation: Quarantine reflects the poem; Quarantine, from the late Eavan Boland. Two, rather soiled, life size figurines [made] from polythene [and] brimming with printed media, represent man and wife. Using related working techniques to that of Jane (produced for the 2017 Liverpool Irish Festival), the forms contain printed statements, statistics and quotes from the literal work: Quarantine. These quotes identify that 20-25% of Ireland’s population was lost to the Famine and related emigration. Further statements reflect on the fact that there was no ban on the export of food, as there had been in the famine of 1782-3. Additional found objects and additions include modelled blighted potatoes, manifesting the poem and the period of An Gorta Mór/The Great Famine.

‘Worst’ is repeated throughout the poem, highlighting the [desparation] of the late 1840’s. Black acrylic paint was applied, using flicking techniques across the inner of the polythene, to represent the anguish and distress the couple endured, [reflecting on] 1847 being titled ‘Black 47’, the worst year of the Famine. The leaving of the workhouse [has been] determined by printed replicas of discharge papers and statements included within the forms. Newspaper articles of the period, relating to the hardships and failing crops, [occupy] the bodies. Ragged clothing is prominent; [demonstrating] how workhouse conditions often meant that clothing was often re-used from those who died from fever and dysentry, without being laundered. The roll-up (cigarette) butts draw attention to how smoking tobacco was commonplace among the poor and labouring class during the Victorian era. This led to tooth decay; studies show that up to 80% of famine victims suffered from poor oral health. The empty bottle of whiskey is equally familiar; the Irish took the drink to the United States, through the period of mass emigration, due to the Famine. A rural location is suggested through the chain and shackle, habitual within farming communities.

Walking on foot -for a prolonged distance- is implied by uncomplicated shoe soles on the outer surfaces of the man’s feet; sufficiently degraded to push the concept of ‘Worn thin’ to the extreme. Women were often barefoot, her shoe soles not present. Hunger is simulated by the inclusion of modelled blighted Irish lumber potatoes. Created from potato clay, [these were] actually produced from flour and cornstarch, but the

The figures are positioned on the floor upon a sack cloth; woven and tattered. This forms the impression of being exposed to the elements; [the couple have lain] the sack cloth down as a blanket to protect from ground frost. Stones are added betwen the figures -at any exhibit- to represent their rough sleeping [and hardship].

The figures are [positioned to indicate/symbolide a] man and wife; an intertwining of hands and an evident physical connection. True to the poem, the wife’s feet are held against the husband’s breastbone; red papers represent the remnant of heat present in his body, whilst the white papers present the notion of frost [which has consumed] the female.

To see a larger version, please click on the image.

To see a larger version, please click on the image.

Alison Little is a visual artist and writer based in Liverpool. She looks to integrate her visual arts and creative writing practice. As an artist, she has worked on numerous commissions from Go Superlambananas to Kirby Town Centre Renewal. Her creative endeavours include the project management of Rags Boutique; a scheme to open a disused retail unit as an exhibition space and workshop venue.

Moving from County Fermanagh in the early 1960’s, to the UK mainland, Alison’s father came to Blackpool first then began working on the motorway systems which were being constructed at the time. He began painting the lines and eventually relocated in the South East, where Alison was born. She has links to family across the area and routes back to when many emigrated to the USA in the 1840’s.

Endeavouring to fuse her creative practices, Alison often illustrates her writings or identifies analogous matter as the focal point for later works. Rape, mental health, impotency and feminist concerns are scrutinised repeatedly; the creation of sculptural form to the penning of adjoining flash fiction, poetry and short stories. Through this, she amalgamates intense personal experiences and fact-based research, identifying with various philosophies and scientific predictions. The outcome is predominantly sculpture and conceptual photography, with varied writing and scripture. More recent works, such as Tittle-Tattle, look to question concepts around homemaking, cleanliness and marriage. Alison provokes through practice, creating a vast array of outcomes.

In 2017 she produced Jane for the In:Visible Women conference at the Liverpool Irish Festival. The installation was accompanied by a shorter fiction work, which was read at the event. The artform and literary piece tied to the Repeal the Eighth Amendment movement, a pro-[choice] movement, which lead to the successful repeal by referendum in 2018.

Alison has had a personal struggle with Covid-19 throughout 2020, succumbing to the virus in late March 2020, which spread to her partner, who was lost to Covid-19, 8 March 2020. After his funeral, the virus re-surged and Alison became ill again. In late August, she suffered a second infection and was to experience the sickness again. Due to lock down -and the almost complete suppression of the creative industries- she has struggled to find work as an artist throughout the year. Mentally, in terms of wellbeing, Alison is now ready to produce new creative works.

Alison has had work published in Hidden Gems, that art in Liverpool website, Dwell Time and Red Brick Writing, in addition to numerous zines. Her blog; alisonlittleblog.wordpress.com is well-read and she releases a weekly article.

Alison is an artist, a writer, creative explorer.

This work was funded by the Irish Government‘s Emigrant Support Programme‘s creative community fund.

#CreativeCommunity

Since the onset of Covid-19, cultural organisations and artists have suffered a lack of creative opportunities because of restrictions on arts venues and engagements. #CreativeCommunity is a once-off initiative by the Embassy of Ireland to Great Britain, the Consulate General of Ireland (Cardiff), and the Consulate General of Ireland (Edinburgh) that provided creative opportunities for Irish artists living in Britain to produce cultural content, shared online. Through Creative Community, the Embassy of Ireland in London and the Consulates General in Edinburgh and Cardiff have supported arts and culture-focused projects with eight organisations, directly engaging with at least 40 Irish creatives across Britain to produce and show their work.

The artists Liverpool Irish Festival has commissioned using this programme, include: Cathy Carter / Andrew Connally / Edy Fung (via Art Arcadia) / Alison Little / Maz O’Connor / Ciara Ní É / The Sound Agents. The links will take you to the individual commissions.

Sub-title: A quick, short, and linear exercise to map the Royal Charter’s failed-return to Liverpool against the history of weather forecasting.

<<<During lockdown, Derry-based Hong Konger, artist Edy Fung has used weather to help motivate her working cycles.

In doing so, she has studied meteorological history, finding links between Derry and Liverpool. Edy’s generated an essay on this, complete with archive images. This sustains a digital relationship with the Festival that began for #LIF2020, advancing our work with Art Arcadia, where Edy is a resident artist.

The connectedness of internationalism, nature and platforming female voices sits within the St Brigid’s Day ethos of progressive acts and equality. We thank Edy for her work and ability to express her layered thinking to bring us something thought-provoking, fascinating and unexpected. You can learn more about Edy at the end of this article.>>>

2020 has overwhelmed the world with how fast every aspect of our daily lives can change for a new normal.

After the pandemic, we have all learned to be humbled by external impacts and environments. Most of us in different parts of the world meandered our way through lockdowns; rethinking our new normal. We have had to learn to adapt to uncertainties, getting used to making our plans with spontaneity, but ready to have them canceled or postponed. It is difficult. We always want an answer for the future; while we look for ways to predict it -analytics, predictions, prophecies- these very methods demonstrate that the need for human beings to ‘imagine’ is inevitable.

My name is Edy; I am an artist who lives and works in Derry, Northern Ireland. I have begun research on exploring atmospheric patterns and their implication on societal and political shifts in macroscale*, bringing these discoveries into a personal, bodily and relatable scale. My artistic practice currently aims to connect human sentiments, affect, weather, politics, science, and technology after the Anthropocene^. This piece of writing, commissioned by the Liverpool Irish Festival, will form the foundation of another online collaborative project: The Meteorological Cartomancer that looks at the beauty of chance and collective feelings. Perhaps, borrowing from the temperament of the Greek Tragedy aesthetic form, I am making some reflections for this day and age; arising from the story of the storm that hit the Liverpool-bound Royal Charter (ship) in 1859 on its journey through the Irish Sea, to incidents concerning geographies of both sides of the water.

* involving general or overall structures/processes, rather than details.

^ the geological time during which human life has impacted the earth.

This is an attempt to trace our desire to foresee the future during uncertain times. It documents the first time in history that humanity came close to future ‘prediction’ with a scientific foundation. I am drawn to look into the 1859 storm that shipwrecked Royal Charter in the Irish Sea. Prior to this, the weather was believed to be an act of God and if a storm came, so be it. This storm -and the resulting shipwreck- holds a vital place in pushing advancement for what is known today as ‘weather forecasting’.

The Royal Charter was a steamship built in Sandycroft Ironworks, on the River Dee, as one of the fastest ships at the time. On the evening of 25th October 1859, the steamship was bound to make the last leg of its 60-day cross-continental journey from Australia. When it left Queenstown -in the south of Ireland- to return home to Liverpool, it encountered a gale so fierce that it rose to a hurricane force 12 on the Beaufort Scale (devised by Irish hydrographer Francis Beaufort in 1805), pushing the ship towards Anglesey (Wales), causing it to sink.

Here, I am excavating materials from the MET archive, starting with one of several (consistent) testimonies documented from people from Wales and Ireland, who recalled the weather and witnessed something more unusual before the storm:

“On Tuesday, 25th, I could perceive nothing at all unusual in the appearance of the weather, till, at half-past seven, when in the neighbourhood of Ballinamar and Ballyporeen, about, I should say, 12 or 14 English miles west of Athlone, the sky being free from clouds, I saw, in the direction of the Pleiades, a meteor. At first, when I saw it, it was about the size of a star of the first magnitude; it advanced swiftly towards me for about four or five seconds, rapidly increasing in size, and appeared to be coming so straight towards where I was that it created alarm; the colour was an intense white light, similar to the electric spark. At the end of the first four or five seconds it changed colour to a bright ruby red, and it seemed (but of this I could not speak positively) then both to change its course and to lose its velocity; while the red colour remained was not more than one-and-a-half to two seconds. It then burst into about, I should suppose, 15 or 16 bright emerald green particles, which, after remaining visible for about two more seconds, disappeared altogether. I saw nothing more that night. I arrived at Athlone about 12 o’clock, and up to that period the sky was quite clear and calm, and there was not the slightest appearance of storm. I was much astonished to hear, on my arrival in Dublin, on the night of Wednesday, 26th, of the violent storm that had taken place on the coast of Wales. […] I could not but think that the fall of the meteor had some connexion with the storm”.

— Thomas. T. Carter (Annual Report 1862, page xl).

This Royal Charter shipwreck, which occurred in the Irish Sea during the closing leg of an incredible adventure back to Liverpool, is linked to the emergence of weather forecasting. The MET Office was not established properly at the time, in the way we understand its function today; it was a position that Robert Fitzroy was taking as the ‘Meteorological Statist’ (Fitzroy’s term), advisor to the Board of Trade for the marine industry and the military. Responding to the Royal Charter’s demise, Fitzroy worked intensively to understand how how the shipwreck could have been prevented. He wanted to avoid further tragedies in the future. Next, we will see in more detail his research on new methods of using barometers, and his invention of meteorological telegraphy and weather map that led to the existence of the weather forecasting system.

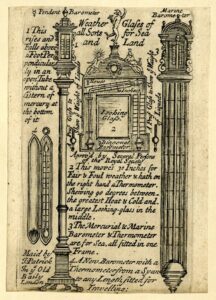

Under pressure: Barometers

In the 19th century, barometers were used inside boats and ships to detect the change of the atmospheric state, mostly for localised usage. These were the instruments most closely associated with a scientific method, reliable enough to provide “some definite idea of the amount of change which indicates unusually violent wind”. Such barometers could react and fall at the rate of nearly a tenth of an inch an hour before the shift of wind occurred. Fishermen and sailors would take this drop of pressure as an indicator of a storm, so they could decide whether to proceed the voyage or to find shelter.

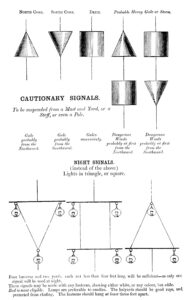

Cautionary Signals, Storm Telegraphy, Lighthouses

In February 1861, Cautionary Signals were initiated.

According to the report of Meteorological Department of the Board of Trade, Fitzroy tried to argue his case about the idea of giving storm warnings using telegraphy before 1836, in American and Europe, “Yet the subject attracted too little popular interest to be taken up by any influential body until September 1859.” (Annual Report 1862, page xi). We do not know the reason why these telegraphic storm warnings were not adopted earlier. The system of measuring wind conditions was already created by Francis Beaufort (an admiral from County Meath, Ireland), but only appeared in his diary in 1806, kept private in navy logs instead of broader application. He created the ‘Beaufort Scale’ to estimate the force of the wind, in a range from 0 to 13. The Royal Charter Storm was classified -under Beaufort Scale- at number 12. In 1859, the same year as the shipwreck, the British Association for the Advancement of Science finally proposed to the government a trial plan by which the approach of storms might be telegraphed to distant localities. By 1862 20 stations were built to establish the telegraphic communication of meteorological facts.

By 1863, more barometers and stations were dispersed on the coasts of Great Britain and Ireland. Locations sending cautionary storm signals -through both electric and magnetic telegraphs- reached 97, including 24 in Ireland (some of which today remain as lighthouses). Blacksod Lighthouse (County Mayo) was constructed in 1864, becoming the first land-based observation station in Europe, where weather readings could be professionally taken on the prevailing European Atlantic westerly weather systems. It became famous for reporting the fierce weather that delayed the Normandy Landings and saved D-Day. What would Fitzroy say about his legacy if he could see that his application of storm telegraphy had affected the ability of trained personnel to change the course of a world war? It was more than merely saving us from a natural disaster, but also humanitarian and political catastrophe when these telegraphic signals came to function.

As good as the technological advancement was, a data cloud did not exist at the time. However, their name today suggests a historic connection to these meteorological transfers and the early days of communications, continuing to demonstrate the importance of the Royal Charter’s legacy.

The first network of meteorological communications has laid the foundation for development towards the concept of a global system of interconnected computer networks; the internet and global information storage. The archive revealed Fitzroy’s continuous contact with observatories including Paris, Berlin, Rostock, Hanover, Turin, Copenhagen, and Gothenburg. Some of his correspondence with Urbain Le Verrier can be read in the 1864 report. Le Verrier is recognised as the pioneer who proposed the concept of a chronological map for storms and weather changes. These are some of the first data visualisations and analytics, now traceable in our data clouds (I am doing this exercise).

Weather Maps

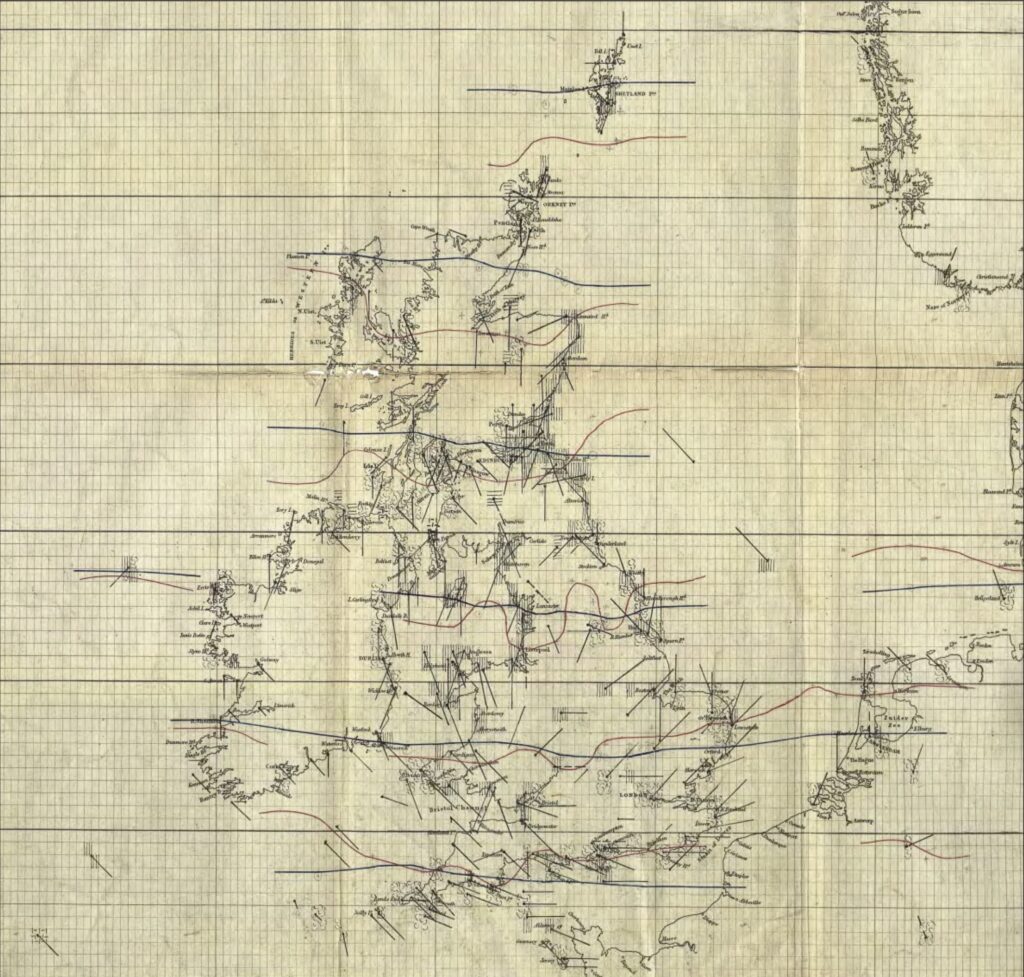

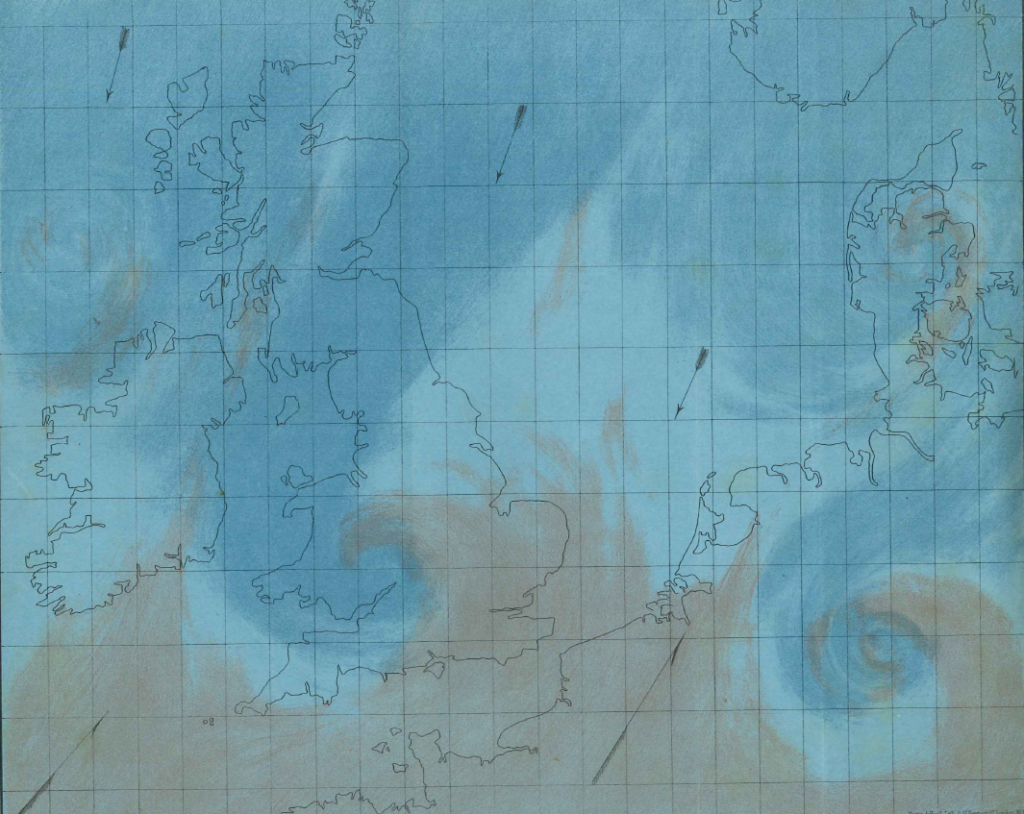

The following are some maps that Fitzroy made to analyse -retrospectively- the Royal Charter’s devastating storm, looking at changes between 25th and 26th October 1859. The arrows were drawn to indicate the wind direction as well as the strength of the wind (in proportion to the length of the line).

These maps were called ‘synoptic charts’, according to Fitzroy, providing a visual synopsis of the weather observations at a or any given time. The below chart by Fitzroy is claimed to be the oldest in the MET collection, suggesting that he could be the first inventor, after Urbain Le Verrier’s vision, of what we understand today as the weather maps. However, it is Francis Galton who is recognised as the first devisor of the weather maps instead (in the method same as today), and he wrote the 1863 book Meteorographica, or Methods of Mapping The Weather in the similar times as Fitzroy’s research. Galton was appointed to substitute Fitzroy’s position and the pivotal figure in the development of weather forecasting in the later years by focusing on remedying the speed and capacity of data collection.

To see these charts as gifs, showing the air movement, click here.

Weather Forecasting

“In August 1861 the first published “forecasts” of weather were tried; and after another half year had elapsed for gaining experience by varied tentative arrangements, the present system was established. Twenty reports are now received each morning (except Sundays), and ten each afternoon, besides five from the Continent. Double forecasts (two days in advance) are published, with the full tables (on which they chiefly depend), and are sent to six daily papers, to one weekly,—to Lloyds,—to the Admiralty, —and to the Horse Guards, besides the Board of Trade“ (Annual Report 1862, page v).

The term “weather forecast” was coined by Fitzroy. Taken for granted today, few of us can imagine that weather forecasting was an impossible concept and so ahead-of-its-time that it encountered plenty of skepticism and restraint. When the first public weather forecast was published in August 1861; its reception was not smooth and was been challenged for a period. Fitzroy had to state, repetitively, that the ‘weather forecast’ differed from general scientific methodology and should be considered as precautionary advisement – “prophecies or predictions they are not:—the term forecast is strictly applicable to such an opinion as is the result of a scientific combination and calculation”. To quote Fitzroy’s own words from 1863:

Many may ask—” Is this system of weather telegraphy sound and advantageous ” ?—If so, why is it opposed? There are no less than four distinct classes of interested opponents, and they should be known. First:—Certain persons who were opposed to the system theoretically at its origin, and having openly expressed, if not published, their objections, are naturally reluctant to adopt other ideas until converted. Secondly.—A numerous body who cannot have had time and opportunity to look tally into the rationale, but do not realise any want of special information, undervalue the subject, assert it to be a “burlesque,” and misquote really great authorities. Thirdly.—A small but active party which failed in establishing a daily weather newspaper indirectly opposed to the Board of Trade reports, and have since endeavoured, by conversation, by letters, and by elaborate criticisms in newspapers or periodicals, to exaggerate deficiencies, while ignoring merit in the works of this office, however beneficial their intended objects. And fourthly, those pecuniarily interested individuals or bodies, who would leave the Coasters and the fishermen to pursue their precarious occupation heedlessly—without regard to risk—lest occasionally a day’s demurrage should be caused unnecessarily, or a catch of fish missed for the London market. 14. Especially referring now to persons who would have the warning signals, but not the ” forecasts” (results of considerations on which the signals depend), may I quote from my “Weather Book” the following words?—”Frequently, remarks in favour of the cautionary signals, but in depreciation of the forecasts, have been made. Their author now begs to say that it is only by closely forecasting the coming weather, and by keeping atmospheric condition continuously present to mind, that judicious storm warnings can be given. Forecasts grow out of statical facts, and signals are their fruit” Weather Book, p. 193. Second edition. (1863 page v)

Less than a year after publishing The Weather Book: a manual of practical meteorology, Fitzroy died by suicide. Despite having proposed the idea of having the central office, to gather weather information (the MET office’s function today), he did not live long enough to see it. The literature he left us reveals his frustration and the great deal of difficulty he faced, while painstakingly realising an accurate weather forecasting system. Similar to the rise of today’s ‘cancel culture’ many rejected its merits, missing the goodwill and opportunities weather forecasting provided to change things for the better. It took a long time to gain traction, until public forecasts were produced in 1879, and became reliable in the 20th century after 30 more years of data accumulation.

Weather forecasting in today’s definition is “the application of current technology and science to predict the state of the atmosphere for a future time and a given location” (Science Daily). The use of both deterministic and probabilistic models is, nowadays, common and continually improved in applications beyond the weather, such as population, economy, energy forecasting and even in the betting industry. Provided the accuracy and the period (normally up to 14 days) that contemporary weather forecast can achieve, we are accustomed to treating the weather reports as valid predictions and make our plans around them. Perhaps this has also fueled our beliefs in the capacity of knowing the future in advance, as long as we have enough scientific tools. Then -logically speaking- one has to believe that the future is fixed and unchangeable, all to be determined by whatever data we have today, if we carry on with our obsession to predict something.

While it might be useful to know the future, we should imagine possibilities -and take positive actions- regardless of whether the future is predicted or not. Like the weather, a lot of things -viruses, traffic, public opinions- operate in a chaotic system; a butterfly flapping its wings can cause a hurricane on the other side of the world. History tells us that working with others, through long-term back-and-forth dialogues (sometimes cross-nationally towards a common goal), was crucial to confront macroscale events and reach solutions together for the betterment of society.

In this difficult time of the Coronavirus pandemic, would it not be more effective if we work together globally, using the best of our technologies, to find future-proofing solutions despite the naysayers, detractors, and decriers? Let us not stop listening to each other, no matter how far we are apart as we are all interconnected, prone to the same danger(s) on this planet.

Fitzroy’s illustration of the Air Currents over the British Isles. From Robert Fitzroy, The Weather Book: a manual of practical meteorology, 1863.

Edy Fung is a multi-disciplinary artist, musician and curator currently based between Derry and Stockholm. She has worked in the conservation of historical buildings and heritage mainly in County Donegal for three years, after graduating from an MA in Architecture at the Royal College of Art. Working at the interface between the physical and the digital, her practice seeks to understand how our material world is conditioned. These include exploring underlying systems, ecologies, ideologies and technological shifts that are dominating our everyday values. She works with images, videos, sound, text, installation and exhibition-making, treating them as ingredients and tools to test her inquiries and speculations about the present world phenomena.

A £1,000 commission is available for a creative project, centred on Irish and/or Gaelic creativity, to form part of #LIF2021.

Irish Film London launches Podcast Series and extends Irish Film From Home Platform.

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to push many film festivals to cancel or move temporarily online, Irish Film London (IFL) has chosen a unique direction for autumn 2020.

The not-for-profit Irish film organisation, based in London, has already proved that it can adapt to online environments. Their St. Patrick’s Film Festival in March was rolled out online within a few days of their planned three-day event being cancelled due to the sudden lockdown in the UK.

From that, Irish Film From Home (IFFH – www.irishfilmfromhome.com), was born. IFFH is the only dedicated online platform for Irish film, TV and animation in the UK with a regular feed of Irish films, talks and film-related resources. So far, over 40 Irish films have been featured on IFFH.

IFL have decided to extend this dynamic online facility for the foreseeable future, as well as remaining in the role of supporting the releases of Irish films in UK cinemas and at major film festivals in the UK.

In addition, IFL is launching a podcast series inspired by the latest and greatest Irish film, TV and animation. It includes recordings of live Q&As and interviews from their festivals and awards ceremonies, in addition to a host of brand-new interviews.

Listeners can expect to hear from people like Fiona Shaw, Roisin Conaty, Lenny Abrahamson, Bronagh Gallagher, Moe Dunford and John Butler, alongside film agencies such as Screen Ireland.

The podcast series will not only keep listeners up to date with insights into the latest UK releases of Irish content, it will also take a look at the future of the industry, with a segment on up and coming filmmakers and actors. IFL will explore the commercial challenges and success of Irish film, TV and animation as well as its wider cultural and social significance.

IFL Founder and Programmer, Kelly O’Connor said, “I can’t wait to share the extraordinary podcasts we’ve recorded with some of our great film friends and heroes. And to bring even more exciting films to our online platform, Irish Film From Home”.

IFL was due to celebrate its 10th Anniversary Festival and Awards in London this autumn with a bold showcase, befitting its ten years of championing Irish film, TV and animation. These will be postponed in order to preserve that official milestone, until November 2021, when the festival experience can match the atmosphere and intimacy that audiences and filmmakers have come to expect from their festival events. They will continue, COVID-19 permitting, with their female-focused film festival for Lá Fhéile Bríde in February 2021, and the St. Patrick’s Day Film Festival in March 2021.

O’Connor said, “Next year we look forward to once again filling the beautiful ballroom at the Irish Embassy for our awards ceremony, welcoming bustling live audiences to sold out cinema screenings and bringing Irish actors and filmmakers onto cinema stages for lively discussions. Not to mention hosting our well-known networking and socialising events, where so many professional and personal connections are made!”.

Now is a great time to start following IFL, to participate in IFFH (www.irishfilmfromhome.com) and to join them on the next exciting leg of their journey.

For all the latest news and competitions, sign up to their newsletter at www.irishfilmlondon.com, and follow them on social media: @irishfilmlondon on Twitter and Instagram, and @irishfilmfestivallondon on Facebook.

Annually, the Liverpool Irish Festival sets a theme and a creative brief.

We work with partners to develop work and engage artists. Bluecoat Display Centre has been a key player in developing design and craft in Liverpool, nationally and internationally, since the 1950s. Who better then to partner with each year to find an Irish talent? Supported by the Design and Crafts Council of Ireland, we make an open call for makers to respond to the theme and our panel makes a selection from the submissions. Last year we chose ceramicist Rory Shearer, whose Derry based work evoked the hills and turf of his country pottery.

Even during Covid-19, 2020s submissions were of a high quality. Ordinarily, we would try not to pick the same medium year-on-year, but Mike’s application was tailored so well to the idea of exchange and he challenged notions of Irishness so well in his statement, he was the finalist. Below, Festival Director Emma Smith, quizzes Mike on some of the concepts raised, along with some probing questions in to the materiality of pottery, high and low culture and stars of the future.

ES: As I read through your submission statement, I noted your mention of Irishness as perceived via “the Irish/cottage/shamrock/American view”. For some Irish people, these values are an intrinsic part of their Irishness, not to be besmirched by the likes of curators/artists /‘intelligentsia’. For them, these items depict levity, light and charm, drawing on Irish traditions that can be taught from these symbolic snippets. Seen as positive, transportable commodities, they help people feel ‘at home abroad’, triggering memories of hills and faces; times and places. For others, it represents a low-taste-level and a (mis)mannered caricature; a nonsense version of a nuanced and deeply emotional national character. I read your view of such items as ‘tokenistic’; do you think there is a place for this or do they take or detract from an understanding of Irish people and their identity?

MB: I can see both sides of this argument; it does show levity, light and charm and appeals to Irish people abroad, particularly to those away a long time. It is an old fashioned, emotional look back at what they think they remember about Ireland. Apart from jumping around on a Saturday night in a Paddy hat, this is not a view taken seriously by Irish people at home and I do not think they represent contemporary Irish lives.

The EU, sojourns abroad for work or holiday, the digital age and a new prosperity have made Ireland a changed place; the old woman in the bed is no longer sipping porter, she is checking her emails.

I think these symbols/images are sort of harmless; there are new stories to tell and new ways to tell the old ones.

ES: Thinking through this brought to mind the William Morris idea that the destruction of capitalism would be necessary for art to flourish! This positioning of ‘low’ and ‘high’ art or culture seems frequently tied to concepts of Irishness, as demonstrated by shamrocks and novelty hats versus the written word, traditional fabrics and making methods.Ceramics often sits in that liminal space between ‘crafts’ and ‘arts’ with similar arguments surrounding it as having high and/or low cultural value. What are your thoughts?

MB: I think there is a place for this material. As you said, it is a bit of fun and I can’t imagine it is taken too seriously. But take a new initiative: ‘The Wild Atlantic Way’; a notion that comes from the same emotional gene pool as the other material is a great success, eagerly embraced by all. I think this is a fine example of a modern take on this question.

If -when I was a tutor in Art school- a student expressed a desire to make products for the tourist trade (some explored niche ideas such as hill walking), I would advise them not to overlook the sentimental pull of certain ideas and clichés and to look at them from a slightly different angle adding a more contemporary slant to them.

I think a lot of the old representation of Ireland does not represent Ireland today, but I would not be beating my breast about it. It has changed from longed-for nostalgic memory to a bit of fun. There is a travel company here called The Paddy Wagon; it takes young foreign backpackers around Ireland. They wear the hats, sing the songs and they give them all the old blarney; they love it. On the other hand, the proliferation of shops in tourist spots -and in the major cities- selling Guinness merchandise (almost exclusively), little of it made in Ireland, can be disheartening.

Yes, Ceramics is in an interesting position. Somewhere in the half-light between craft, design, the decorative arts and art, but it is quite easy to position the various strands. Intent is all! The craft potter makes domestic ware; the designer designs for the industry; the decorative arts have their conventions and artists deal with many issues including social and aesthetic. The only common denominator is the material and the processes. Some see it as a kind of hierarchy. We all need someone to look down on!

ES: The materiality of ceramics seems to be part of what locates them. Would your work would be the same if you were making it with Mexican barro negro or Chinese kaolin? I don’t just mean the overall finish or surface aesthetic, but in the forms it leads you to? One cannot do with terracotta what can be done with porcelain, so does Irish clay imbue the sculptural form innately and does its historic content play any part in the form you take it to? Is there an exchange in this process between artist and material?

MB: In my case, the concept comes first. The material is of course considered, insofar as it can do what the concept demands. Makers will choose a particular material like porcelain for what it will bring to the expressive outcome. As we don’t have exploitable clay deposits here, I use clay from Northern Ireland, where it is made using imported materials from the UK and beyond. It suits my work process well. It is a robust utility body, ideally suited to forms I make and the low firing temp I require. I cannot say that this particular clay influences my work conceptually.

ES: Ceramics have a role in all lives. It is likely that the nationality of the item is less important than the value of its aesthetic, function or place in a user’s world. Therefore, should Irishness play any part on the form and does it require such a connection?

MB:I never think of myself, or my ideas, as being Irish while I am making. Ideas come and develop as things get made and are appraised. It is a never-ending chain of exploration, frustration and a little joy. I live in a small city near the west coast of Ireland. I travel up and down the coast often. I draw the landscape, collect objects; manmade and natural. I feel close to Ireland and am happy to be Irish and I am sure that this life influences how and what I make. I think attempting to build Irishness into the form would be a contrivance and could possibly muddy the waters in the creative expression or interpretation of the concept.

ES: Are there any rising stars in Irish ceramics you think we/audiences ought to look out for?

MB: Frances Lambe, Sara Flynn, Mandy Parslow, Grainne Watts, Alison Kay and Nuala O’Donovan.

We would like to offer Mike our sincere thanks and congratulations for being involved in this year’s In The Window and recommend any Irish maker look out for our new artistic call in 2021. See more of Mike’s work here or visit his work in the real world at Bluecoat Display Centre from 1-31 Oct 2020. His statement is below the gallery for those who wish to know ore about this particular project.

This is exhibit is supported by the Design and Crafts Council of Ireland.

STATEMENT: Exchange

When in art school in the 1970’s, ceramic design students we were desperately trying to shed the Irish/cottage/shamrock, Irish/American view and imagery of Ireland, which dominated tourist products and literature at the time. The tourist market then far outweighed the domestic market for craft and design products and so, could not be ignored. While quality Irish craft and ceramics has developed in the intervening years, it has done so alongside a combination of persisting staged Irish product offerings and a secondary -perhaps more thoughtful, but still shallow- emblematic or caricature-like selection of products that outsells art and craft ceramics. So today’s stories, as far as products representing and reflecting Irish culture are concerned -it seems to me- fall into two categories: firstly, those that are driven by and trade on associations and imagery of a notion of Irishness or Irish tradition -for example reproduction Celtic iconography, Guinness t-shirts, visual representations of animals, landscape, Irish colloquialisms etc., on products and in prints; and –secondly- those stories that emerge through work that is conceived and produced by creative Irish individuals; stories and artefacts that carry with them an authenticity that finds a different type of audience; smaller, more focused; recognising Irish origin, but more concerned with the underlying ideas rather than with Irish tokenism.

At the time I studied at Limerick School of Art and Design all the tutors of ceramics were English and brought with them a long tradition of ceramic making from Medieval pottery to the factories of Stoke-on-Trent. The Irish do not have a continuous history of ceramics, and with British involvement in Ireland for so long, imported English ceramics became as common in Ireland as in any other part of these islands. So, the English tradition became the Irish tradition, prized cream jugs in our grandmothers’ dressers all carried the great Stoke trademarks. The diasporic exchange was essentially one-way. However, as students graduated from art, craft and design courses in Ireland over the decades since the 1970’s, they slowly began to develop and create identities for themselves through their output. It is difficult to argue there is any consistent cultural theme running through this work, least of all a particularly Irish one. However, it is true to say that that educational exchange in art and design, which occurred as a result of the developing Irish creative education institutions hiring staff from outside Ireland, had a deep and lasting impact. This exchange is now no longer one-way, as Irish artists, designers and craftspersons who benefited from the input of international educators, achieve success at home and abroad.

In an effort to boost the development of design and craft -and almost concurrent with the arrival of international educators into Irish creative third level education- the Irish Government established the Kilkenny Design Workshops (1963). Its aim was to improve the quality of Irish design. Each department of this design and development agency, including ceramics (where I was initially placed), was led by a designer from outside Ireland. I spent two years working at KDW and mixed with a wide range of designers in different fields from diverse backgrounds. It was very interesting to see how they, as designers, brought their experience and culture to bear on the work they did in Ireland. This exchange positively impacted a slew of young Irish creatives and contributed to a significant amount of the creative capability manifest in current Irish design.

Later, I taught on a ceramic design course. My students and I wrestled with the problem of Irishness in design, how to make work that felt like it came from Ireland yet looked beyond these shores to a modern Europe. Scandinavia was an obvious model where they used traditional materials, a combination of new and old processes and centuries of design development. However, it became clear that the quest to imbue our work with “Irishness” was not a premise upon which creative work could be based. Irishness, if it was something that could be a feature of a product or artwork (I personally doubt that it can be), would have to emerge through the work over a sustained period of time, through bodies of work by Irish artists, designers and craftspersons. After many years, I can say that I see enormous creativity, artistry, and superb craftsmanship all around, but it is hard to pin down a sense of Irishness in the work produced in Ireland. Clearly, in fine art -where Irish themes and landscape are the subject matter- there is a fundamental Irish connection. Some craft brands have become strong Irish brands such as Nicholas Mosse Ceramics, which draws on Irish flora and fauna themes in its decorative motifs.

One area where perhaps there have been significant international exchanges through traditional Irish design may have been in the textiles sector. In the emerging Ireland of the 1950’s, woven products from Ireland -Donegal Tweed, Foxford Woollens, Aran sweaters- had an international impact (especially in the United States). This exchange has continued to the present day and the cultural element -Irish traditional apparel and textiles- has found new connections and markets alongside its older markets. The “Irishness” of these products, unlike that of more recent design and craft output in Ireland, is, as in the case of the Scandinavian tradition, rooted in local materials and processes.

In my own work, sometimes intentional, sometimes accidental, my exploration of surface texture and colour seems to reflect the world around me. I believe that land and seascapes local to me, and unique to Ireland, drive the decision-making process that I use to build up the surfaces of my ceramics. Insofar as these surfaces derive their nature and energy from the influences surrounding me, they certainly reflect my Irishness.

The forms I have been making for some time now, upon which the above surfaces are developed, also have a certain Irish connection. Common domestic shapes such as pitchers, metal jugs and pourers have been creative resources for the shapes I have produced and new shapes that are evolving.

In conclusion, the exchange that took place during my education at LSAD and subsequently at Kilkenny Design Workshops has had a long lasting and deep influence on my work. What I make now, although it falls between utility and art, is neither. Yet it has its roots in my training, and in the influences of those I met from other cultures, during my education. As I exhibit at home and abroad, a new exchange is taking shape for me and informs my ongoing work.

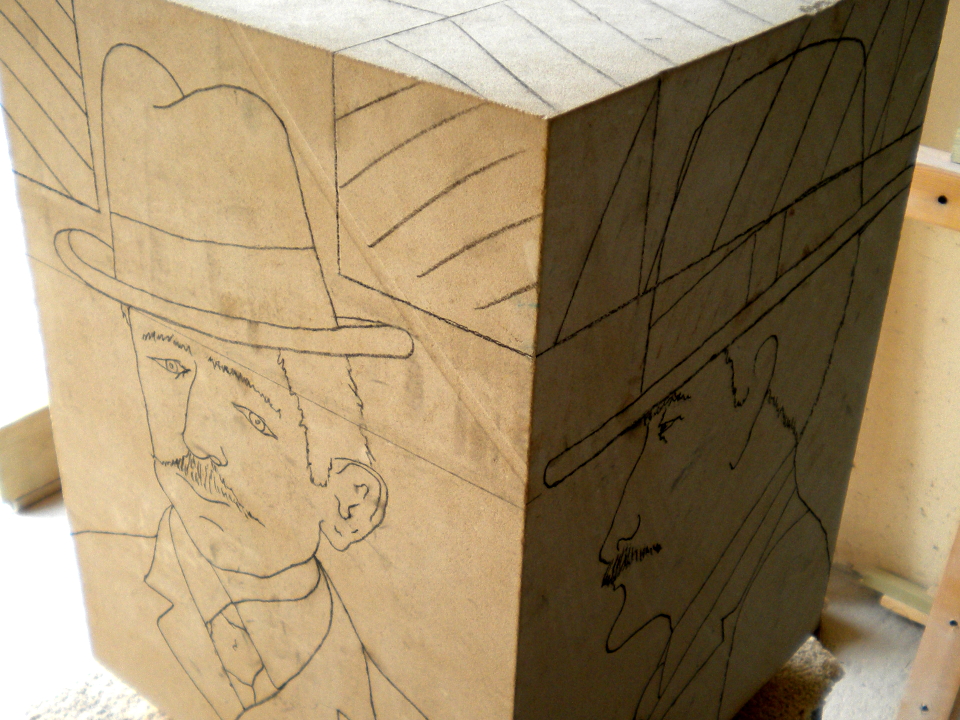

Nigel Baxter is a Liverpool Irish stone mason.

Liverpool has a ubiquity of stone – from the smooth Asian slate of Liverpool ONE, to the warm red local sandstone of the Anglican cathedral; the corbels of St Nicholas’s Church and the Irish granite of the dock kerbstones and Irish Famine memorial. Interesting for us then that Nigel’s most recent work has revolved around two creative men, of Irish lineage, where an exchange of respect has generated legacies for each. Nigel tells us why.

There were three main factors that set me on a course of discovery about Seamus Murphy and Robert Tressell.

Part 1: Seamus Murphy arrived in my life by chance, whilst -as an enthusiastic and eager stone carver’s apprentice- I stumbled across his semi-autobiography Stone Mad in my local London library. Dwarfed between large art reference volumes, its insignificant size was compensated by its title. It was a book that transpired to inspire one’s life and it became my personal bible. We had a lot in common. Although from different generations, our training and experience were mirrored in such ways that I came to conclude, much later, we shared an affinity only craftsmen identify with; a sort of mutual bonding. Even though we never met (he died two decades before) I felt connected through his writing and -indeed later- this was substantiated when meeting his children during the project.

Whilst talented and recognised as one of Ireland’s great sculptors, Seamus was a quiet reserved character and (indicative of many creative people) very modest about his skills. This was demonstrated by a visit to his native city, Cork, where despite many examples of his work I found nothing to identify the man himself. It was as if he had dissolved into obscurity, leaving a trail of ghost-like artwork. So, who better than I to carve -in stone- his portrait, thus immortalising an important craftsman who had influenced my creative development? I was determined to dig deeper.

My first port of call was his art college. Among my findings was a list of short films and documentaries, relating to Seamus and his craft. This finding developed in to a friendship with a film director, who had aired a life documentary on Irish television. Our meeting was overwhelmingly successful and a deal was struck to film my project. Additionally, I was offered a residency at the art college, with full workshop facilities. This was the opportunity I had hoped for and, armed with this encouragement, I sought approval from Seamus’s immediate family, seeking examples of images of him. On producing a limited number of photographs it was collectively agreed to opt for a posed publicity shot and an editorial photograph, each taken in mid-life, which we felt showed his finest qualities, both for age and imagery.

The carving of stone is an intense experience, not to be hurried. Indeed each craftsman has their own pace and relationship with the material. For me, I find that speed is not a requisite to final accomplishment; my technique is relatively quick and therefore the carving of a full size bust, depending on the stone, averages between 120 and 150 hours. In Seamus’s case the procedure took longer, to allow for lighting and camera angle adjustments, working from just two images.

We had a number of inquisitive visitors, due to press and college publicity. Among them was one of Seamus’s daughters. Whilst not unaccustomed to being in a carving workshop, she viewed the developing image of her father with a mixture of trepidation and relief; although it had been some years since his death (she was in her eighties), and with recognition fading, there was delight to finally witness an immortal reminder of her father’s greatness, for me the ultimate accolade.

Part 2: Hastings (East Sussex) is the quintessential English south coast town. It has predominately retained its quirky late-nineteenth century seaside characteristics, still attracting a colourful hotchpotch of inhabitants, mirroring the social backdrop described in (possibly) one of the most poignant political/social stories to ever be written. Its title was not unfamiliar to me, having an odd ring of eccentricity about it, so it was only natural for me to pick up a copy of The Ragged Trousered Philanthropist whilst browsing in an alternative book shop nearby.

Robert Tressell was an Irishman, born in Edwardian Dublin. He lived such a life of diversity that only someone with his experience, coupled with that talent, could reiterate -so succinctly- the life of the working classes of the time. There were so many positive testimonials, by some very learned people, arising from this book that I needed to pursue the man behind the pen. My investigations took me on a journey to Dublin, uncovering the complexities that fashioned his fascinating mind; from child to man.

When creating a bust the challenge is not just about the physical execution, but interpreting characteristics…this can only be done when you are aware of as much of that person’s history as is possible. Indeed, it’s not unusual for the features to appear from the stone block, to catch me in conversation with them, expounding theories and unanswered questions for which I know there to be no answer. This only encourages my drive to illicit and expose as much about the person as possible from the inanimate stone.

Discovering quality images of Tressell was even harder than of Murphy. In the literature about him, only one grainy black and white full frontal image appears, used repeatedly. Additionally, one crowd photograph –an aerial shot from behind- depicts Tressell among 200+ people wearing his very distinctive Homburg hat, which he wore unfailingly. My use for this was to capture his hairstyle, which he wore thickly as opposed to the favoured short back and sides of the times.

Sadly, there was little interest from local authorities or dedicated Tressell followers, despite radio and press coverage. This I’ve come to accept when an artist undertakes a project that hasn’t been officially recognised or commissioned. In both my Murphy and Tressell projects there has been little recognition from those claiming an overall interest in their causes. To this I’m quite resigned; these projects are my personal statements that demonstrate there are people past who deserve recognition and immortal recognition.

Part 3: This brings me to my third layer of inspiration: the links between these two men. Initially it wasn’t obvious to me, but soon I became aware of the similarities. Along with their Irish heritage, Murphy and Tressell’s lives run in parallel. For the most part their lives correspond to creative skill development and use; each sharing a literary talent born out in their books, written with dedicated passion on their respective subjects.

Whilst Seamus died in his home town of Cork, Robert sadly died here in Liverpool, attempting to earn his and his daughter’s passage to Canada. There’s similarly little significant remembrance of either.

I now reside both in Cork and Liverpool. As for our notable characters of creation? They still hide behind a cloak of obscurity in storage in their respective cities, waiting for public recognition that they both so rightly deserve.

Nigel has a project page for his Seamus Murphy work, which you can access here.

Art Arcadia and one of its residents -Gregory McCartney- look back at last year’s #LIF2019 partnership exhibit, sharing the work of Paola Bernadelli and Locky Morris.

Last year, Art Arcadia and the Festival tag-teamed a residency to create Watch me grow/a trip here a trip there, an installation spanning the duration of the Festival from its base at Sefton Park Palm House. Paola Bernadelli fuelled a visual dialogue with Locky Morris, an artist living in Derry (Paola’s usual home) creating a series of images, which we printed daily as part of the exchange. It was an exchange of ideas, spaces, talents… and the results are charming, funny and unexpected. We’ve set up a gallery of the images below. Impressed with the imagery and concept, Gregory McCartney (Art Arcadia residency alumnus) reviews the work.

Everything eventually becomes black and white. Grand narratives get replaced by other grand narratives and we are seemingly always placed in somebody’s political, economic or social taxonomy. Even the democracy and fragmentation that the internet promised has failed to live up to expectations. Subtlety is a threatened species in the online eco-system. It’s a place where everyone shouts. Even in an art world that supposedly embraces diverse approaches it’s the overblown and loudest work that often get all the attention. Which isn’t to say I have any objection to bombast. Anyone who has encountered anything I do can confirm that I have a taste for the epic. However, the epic can be found in the most subtle, fragile, ephemeral thing. The biblical passage in which God appears to Elijah as a breeze is a classic metaphor for beauty and awe in the gentlest of circumstance.

And Art Arcadia/Paola Bernardelli and Locky Morris’s Watch me grow/a trip here a trip there residency work is epic in the classic and contemporary sense of the word. Each day, Paola Bernardelli would wander around Liverpool producing a photo, to which Locky Morris would respond with one created in Derry. The result is fascinating; an abstract, subtle, sometimes sensuous dance of form and formlessness.

Another thing about contemporary existence is that it is not abstract. You’d think that we’d be exhausted from the on-the-nose directness of our lives and perhaps dive into a mysterious abstraction, but we don’t for the most part. We just try to shout louder than everyone else. What I love about Bernardelli and Morris’s correspondence (and it is a correspondence, if not the traditionally textual variety) is its epic quietness combined with a bubbling vitality. This isn’t an easy thing to create or even maintain. Think of all those paintings, those studies in form and expression slowly fading in modern art museums; the air and light seemingly draining any vitality they originally possessed from them. They actually look better in photographs. I’m doing some of these artists an injustice of course; Yves Klein’s paintings look as vibrant as ever, for instance.

Bernardelli and Morris’s photographs -whilst in the same painterly tradition- expand and update it to a wonderful degree, including the detritus, vibrancy and humour of contemporary Liverpool and Derry’s everyday existence. Every part of these photos is important and the content -though of ‘everyday stuff’- is certainly not banal (to use a word favoured by dodgy philosophers and unimaginative curators). These photos are however political (with a small ‘p’) in the sense that they do reflect the forces that shape their and our world. They don’t preach or offer any definite answers though. This would limit them. Art, to paraphrase James Thurber, doesn’t always have to be first at the barricades.

I’ve always been a bit conflicted about residencies. On the one-hand they are brilliant in generating experiences of new and unfamiliar places and people. I had a great residency in New York a few years ago. On the other hand, it’s pretty much impossible to go on a lengthy residency if you have a job, or a family, these days. I like the snapshot nature of this residency: a few days intervention in Liverpool culture for Art Arcadia resulting in work for Locky Morris to respond to. Perhaps there’s a prescience to it; we now find ourselves corresponding remotely and often obsessing over the minutest of details. In fact, it is somewhat ironic that it’s such a tiny, invisible to the naked eye, virus that has caused such a massive upheaval in our daily lives, leaving us grasping for familiarity and often at odds with one and other.

There’s joy, sadness, pathos in these photos. In a time in which we literally cross the road to avoid people it’s important to remember we still are human. In a time where connection is potentially life threatening these photos show the power and the poetry of connecting.

I’ve liked Locky Morris’s work for a long time, in particular his (for want of a better word) ‘post-Troubles’ practice. Those little humorous interventions in the everyday brim with warmth and power. If I can show you ‘fear in a handful of dust’ I can also show you love, hate, sadness, joy. In other words, I can show you humanity and what it is to be human. We need this more than ever these days. Similarly, I have liked the ‘process’ that is Art Arcadia; its questioning of the concept of the residency; its integration of the internet and social media, in particular into this concept. Locky can take part in a residency without leaving home; I was part of Art Arcadia’s excellent Lockdown Residencies series (http://artarcadia.org) without leaving my sofa.

One thing tragedy does is make the world a bigger place and at the same time a smaller one. The pandemic is raging across the world making it strange and distant, but we are confined to our home towns and to our computer screens. It doesn’t mean we can’t come up with powerful, beautiful things though. As this project proves: we can find meaning and indeed new meaning in the smallest of things and in the most familiar places. This is vital, particularly these days.

Gregory McCartney is editor of Abridged https://www.abridged.one/

Paola Bernadelli is Founder and Director of Art Arcadia (Derry, Northern Ireland) with whom the Festival have an ongoing partnership. She stayed in Liverpool for the duration of #LIF2019, acting as artist, communicator, curator and set builder! The Festival is indebted to Paola for her determination to battle the difficulties, take opportunities and collate an insightful, competent and humorous body of work. Locky Morris’s unique perspective on collective identity, experience and humour played a witty hand in the final exhibition and exemplifies his wry eye, compositional skill and ability to forge open dialogue. For #LIF2020 we are bringing Edy Fung in as a digital resident, so hope there will be much more to this Derry-Liverpool exchange and conversation.

University of Liverpool and the Institute of Irish Studies have today announced five-day programme of cultural events. Commencing Mon 11 May, the programme focusses on film, drama, music and poetry.

To read the full news piece, click here. You can also find the programme, here.

This is our programme overview, complete with LIF‘s recommended highlights (*). Use the links to navigate direct to the events as they are published:

Mon 11 May 2020

Tues 12 May 2020

Wed 13 May 2020

Thurs 14 May

Fri 15 May 2020

We hope this gives you the arts and culture nourishment you need during lockdown and look forward to sharing LIF’s events in the not too distant future.

Irish artists/makers are sought for In the Window art/craft exhibit at the Bluecoat Display Centre, linked to #LIF2020 theme “exchange”. Submit product/exhibition ideas by Mon 6 July 2020 (extended from 1 Jun). Work can be drawn from existing collections, but preference is given to work made within the last 2 years.

Note: We understand Coronavirus/Covid-19 *may* affect dates and timings for this exhibit, but presently we are living in the hope that lock-downs will have passed for October. Consequently, we are pursuing the commission until such a time as we cannot. At that point, if we cannot make Oct 2020 dates work, we will consier online galleries, postponing physical exhibits and agreeing dates as we proceed.

For five years the Bluecoat Display Centre has partnered the Liverpool Irish Festival, selecting a contemporary Irish craft maker to exhibit here – In the Window– for the month of October. This year, we would like the In the Window maker to link in to #LIF2020’s theme “exchange”, inviting submissions from makers across crafts and the applied arts.

Bluecoat Display Centre and Liverpool Irish Festival are delighted to be working with the Design & Crafts Council Ireland (DCCI) again, who will support the call out and contribute towards transport costs. The selection panel will be made up of representatives from the Bluecoat Display Centre, Liverpool Irish Festival and DCCI.

Open to any professional Irish craft maker, living and working in Ireland; in any discipline (although consideration should be given to suitability for display In the Window (see the dimensions in image below)). We ask that the work shares a link with Liverpool Irish Festival’s 2020 theme: “Exchange”. Use this link to read the full artstic statement and creative call for #LIF2020. The exhibition work does not have to be new but all work should be available for sale. Send your exhibition ideas/product images by email to: [email protected]. We require a

The selected maker will be announced within 6 weeks of submission deadline.

Click to expand.

Bluecoat Display Centre (BDC) is an independent, regional centre for artistic activity that brings together craft makers and the public in an environment that encourages creativity, collaboration and the exchange of ideas. A registered charity since 2010, based in Liverpool city centre, BDC runs a gallery; education and community outreach programmes and provides over 60 local and 300+ nationally selected contemporary craft makers and designers a retail platform to display and sell their work. BDC originated as one of this country’s earliest craft and design galleries in 1959, the first public gallery space within Bluecoat; who are our landlords. We are an advocate, facilitator and audience maker for contemporary crafts.

Bluecoat Display Centre (BDC) is an independent, regional centre for artistic activity that brings together craft makers and the public in an environment that encourages creativity, collaboration and the exchange of ideas. A registered charity since 2010, based in Liverpool city centre, BDC runs a gallery; education and community outreach programmes and provides over 60 local and 300+ nationally selected contemporary craft makers and designers a retail platform to display and sell their work. BDC originated as one of this country’s earliest craft and design galleries in 1959, the first public gallery space within Bluecoat; who are our landlords. We are an advocate, facilitator and audience maker for contemporary crafts.

The Design & Crafts Council Ireland (DCCI) is the national agency for the commercial development of Irish designers and makers, stimulating innovation, championing design thinking and informing Government policy. DCCI‘s activities are funded by the Department of Business, Enterprise and Innovation via Enterprise Ireland. DCCI currently has over 60 member organisations and more than 3,000 registered clients.

The Design & Crafts Council Ireland (DCCI) is the national agency for the commercial development of Irish designers and makers, stimulating innovation, championing design thinking and informing Government policy. DCCI‘s activities are funded by the Department of Business, Enterprise and Innovation via Enterprise Ireland. DCCI currently has over 60 member organisations and more than 3,000 registered clients.

Liverpool Irish Festival (LIF) brings Liverpool and Ireland closer together using arts and culture. It is this use of arts and culture as an instrument for observing, learning, sharing and debating Irishness, in the particular context of Liverpool, which makes us unique. We represent Northern Ireland, the Republic and the Irish diaspora’s creativity throughout the festival. Our thematic approach to programming, critical-thought and curation develops depth, resonance and inclusion. In this context, we believe the Liverpool Irish Festival is the only Irish arts and culture led festival in the world. We can’t find another!