Over the years, the Liverpool Irish Festival has considered Irishness in terms of creative legacy and production. We have investigated Irishness via dual-heritage lives; the genetic make-up of the city; historic migration and contemporary identity theory (post-Brexit).

Though we have discussed migration and migrants a lot -including causes, diaspora groups and long-term effects- we have given less consideration to modern-day views of domestic migration, or how Irish migrancy is compared to other ‘transient’ communities.

We were contacted by Aileen Bowe, an editor for Immigration Advice Service, who had some interesting points to make on the subject, as well as some thoughts on why arts and culture can help community cohesion.>>

How Irish migrants in Britain have navigated the complexities of cultural expression

We are all familiar with the nature of the special relationship between Ireland and the UK. The long history of migration between the two countries means that the idea of separate ‘Irish’ and ‘British’ identities has become more blurred for people with immigrant backgrounds.

A common perception is that anti-Irish sentiment in the UK today is at a relatively low rate. However, the reality is that there is not enough evidence to make that claim, in part due to the lack of available statistics on white hate crime. In fact, some Irish communities in Britain have expressed that there has been an increase in sectarianism and aggressions against the community.

Add to this the experiences of people with dual heritages and dual ethnicities and the situation becomes even more complex. There is another prevailing perception that ‘Irish immigrants’ equates to ‘white immigrants,’ but where do Irish immigrants of colour fit into this matrix? For example, how have the influences of Black Irish people in the UK been recognised?

When it comes to tackling the multifaceted challenges of community integration and anti-racism initiatives, it has been shown that one of the most effective approaches is grassroots-driven activism and the work of arts and cultural organisations. These groups provide spaces for people of all backgrounds to reflect on issues and uncover new ways of thinking and cultural expression.

The Irish in the UK

The phenomenon of how second-generation migrants identify themselves is well documented. Studies have found that the motivation for moving has a major impact on how well new migrants and their families assimilate into the new country and its culture.

Traditionally, many Irish people have migrated for employment and a better quality of life, which was not necessarily always a free choice. Conditions in Britain were sometimes harsher than in Ireland, meaning that generations of Irish people suffered from high levels of poor mental health and excess mortality rates.

A 1996 study found that in the second-generation Irish population in the UK, there were “significantly higher” mortality rates when compared with the wider UK population. The authors drew the conclusion that there was evidence of enduring challenges caused by the lived experience of being in the UK, as well as socioeconomic, cultural and lifestyle factors.

Although it might appear that British society has had the bigger impact on Ireland, it’s undeniable that Ireland has shaped the culture of the UK. From the high number of Irish musicians studying and performing in the UK, to beloved television personalities, fashion designers, chefs, and artists, there has been a major contribution to the British arts and cultural scene from Irish emigrants.

Despite the fact that nowadays only between 1-3% of the Irish population speak Irish daily, with the vast majority of people in Ireland speaking the language of the British colonisers, there are many instances of the influence of Irish on the English language (think ‘brogues,’ ‘hooligan,’ ‘phoney,’ and ‘whiskey’).

The constantly evolving attitude to immigration

Known as the ‘second capital of Ireland,’ Liverpool is one of the best studied regions of Irish immigration to the UK. With an estimated 50%-75% of Liverpool residents claiming some Irish connection, it is fitting that Liverpool is today held up as an example of the many positive benefits of integration. However, this was not always the case.

Known as the ‘second capital of Ireland,’ Liverpool is one of the best studied regions of Irish immigration to the UK. With an estimated 50%-75% of Liverpool residents claiming some Irish connection, it is fitting that Liverpool is today held up as an example of the many positive benefits of integration. However, this was not always the case.

While it can sometimes be tempting to focus on the contributions of just the Irish immigrants to Liverpool and the UK, it is undeniable that immigrants from all around the world shaped the UK in multiple, many faceted ways.

Whether it’s the contribution of healthcare workers, new influences on food and drink, the many contributions from scientists, and the artistic impact of people from diverse nationalities – the UK as a whole could be considered a shining example of the benefits of immigration and integration.

However, one point that is important to consider is how people from certain immigrant backgrounds were viewed as being more or less ‘worthy’ than others. The current discourse in the tabloid media is a binary view of immigration as being harmful for UK citizens as a whole, with Britain’s exit from the EU being cited as one of the outcomes of this harmful rhetoric.

Indeed, even today in official Gov.uk materials, “taking back control of our borders” is cited as one of the main reasons for the UK leaving the EU, with the unspoken implication that the border had been overrun or hitherto outside the control of immigration authorities.

It is probably quite logical that a country that colonised 90% of the world is today overly preoccupied with its own borders, especially one without a strong understanding of its history (evidenced by the fact that 59% of the UK population believe the Empire was something to be proud of). In fact, a common theme across anti-migration sentiment is a sense of dissonance and disengagement from facts.

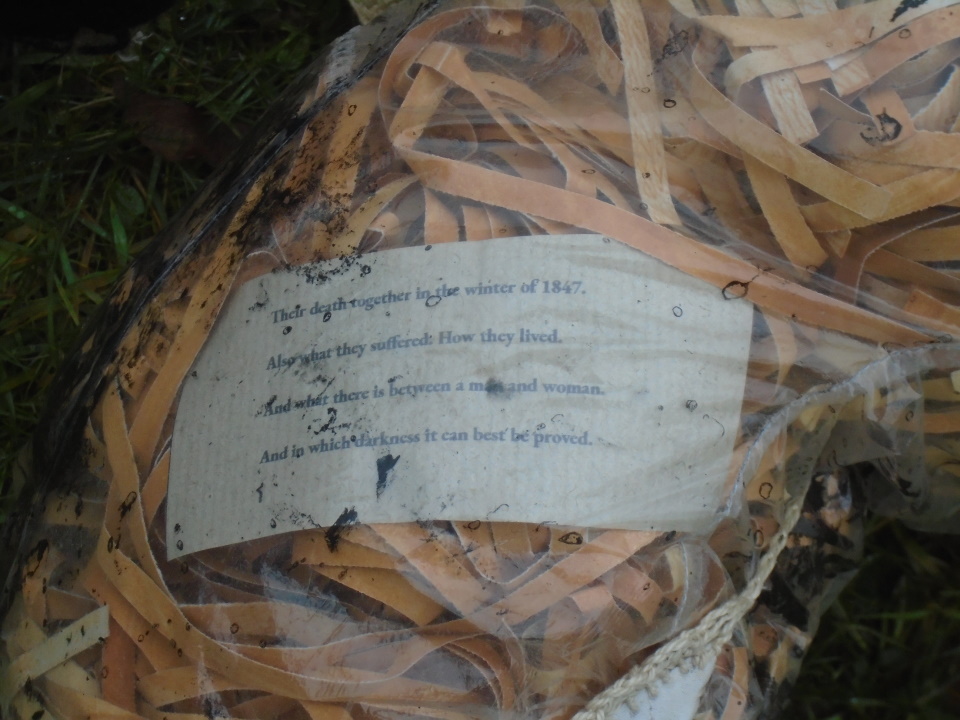

The often-dehumanising process that migrants must undergo in order to enter or stay in another country is reflective of how attitudes to immigration and the parameters of what is acceptable and not are constantly shifting. As all Irish people know, the Great Famine destroyed the country in many ways, essentially halving the population from 8 million to under 4 million (from which it has never recovered, and is the only European country to have a smaller population today than in the 1800s).

There have been arguments that the Famine was a genocide committed by the English, but this has been debunked by historians. What is undoubtedly true, however, is that the British government failed to put in place measures that would have alleviated the starvation of the poorest people in the country, resulting in hundreds of thousands of preventable deaths.

And so, it was Irish migrants who came to the UK to escape poverty and starvation, but who were treated poorly and until relatively recently, had poorer life outcomes than UK-born citizens.

In a world where colonisation has touched almost every area of the earth, the overwhelming media portrayal of migrants is from a negative lens.

Organisations like Irish in Britain and the Liverpool Irish Festival have been doing stellar work in raising the profile of Irish immigrant communities and challenging the narrative of the ‘lazy, uncultured migrant,’ who ostensibly adds nothing to the host country.

Organisations like Irish in Britain and the Liverpool Irish Festival have been doing stellar work in raising the profile of Irish immigrant communities and challenging the narrative of the ‘lazy, uncultured migrant,’ who ostensibly adds nothing to the host country.

These programmes serve as important institutions that provide an alternative perspective to the mainstream portrayal of immigrants in the media and popular culture.

Rejecting mainstream framing of immigrant communities

Despite the extensive studies into the topic of migration, there is a hard-to-challenge perception that some immigrant communities are acceptable, while others are less so.

For some Irish immigrants in the last 50 years, they have had the advantage of appearing British, with skin colour and language being less of a barrier than some other nationalities.

“They (the Irish) live on beasts only, and live like beasts. They have not progressed at all from the habits of pastoral living…This is a filthy people, wallowing in vice”- Gerald of Wales.

The language used here by a historian around the year 1188 is not dissimilar to the discourse applied today to people emigrating to the UK or around the world. Interestingly, some historians believe that Gerald wrote such an account as part of an effort to gain favour with King Henry II and justify his invasion of Ireland.

The role of social media in amplifying anti-immigrant attitudes is a topic that is frequently researched, but it is also important to consider how language is framed by supposedly reputable news organisations, and how this filters down to individual groups online.

A seminal 2008 paper into the discourse around refugees, asylum seekers, immigrants, and migrants (RASIM) in the UK press found that the media overwhelmingly framed these groups into some common negative categories. These categories included suspicion around the legality of their entry into the UK, economic burden, economic threat and the return of these people to their country of origin.

While the study found that 98.1% of tabloid mentions of RASIM were negative portrayals, the ostensibly more objective broadsheets published negatively focused articles on this topic 75.6% of the time.

As in the case of Gerald of Wales, it is worth considering whose agenda it serves to push anti-immigration rhetoric and foster distrust against migrant populations.

A look to the future

Community organisations showcase not just the benefits of immigration for the host country, but also focus on shared values, such as arts and culture, applying a progressive lens in advocating for the dignity of all community groups.

Similarly, Liverpool Irish Festival consistently shows strong support and solidarity for groups that may be facing inequalities or prejudice. For example, the organisation was quick to offer direct support to the Chinese community in Liverpool following the start of the global COVID-19 pandemic, when there was a significant increase in hate crimes against Asian communities.

Not all groups of people face the same inequalities: some face much worse conditions than others. It is important for all communities to help raise each other up, especially those groups who have undergone poor treatment themselves in the past.

With the dual challenges of COVID-19 and Brexit likely to impact on the UK and its inhabitants for the foreseeable future, it will be important to bear in mind that there are more elements that bring people together, and attempts to divide communities should be steadfastly rejected.

The ultimate goal for most people is to live a happy and peaceful life. When people from different cultures come together to share their life experiences and their ways of life, incredible things can happen. When you have more open-mindedness, tolerance, and empathy in a community, the stronger its ability will be to provide space for growth and development for each member of that community. Ultimately, no matter a person’s background, living in peaceful co-existence is something that everyone should strive towards.

<< Aileen Bowe is a writer and correspondent for the Immigration Advice Service, an organisation of immigration solicitors that provides legal aid to forcibly displaced persons.

Image credits: Aileen Bowe. Merseyside from the air (2019) and aeroplanes on the ground.

Like Aileen, it is our inate belief that by sharing creativity and culture; creating safe spaces for discussion and hearing one another; we can build stronger, safer, more connected communities.

The above article has not been fact-checked -nor does it necessarily present the precise views of the Festival- but it is presented here as a thought-piece by a collaborator we believe has an important point to make and a specific vantage that many of us are not permitted.

If you have papers you would like us to consider for the website, please email us at [email protected].